The world marks the International Day of Democracy today, with at least one optimistic statistic: the number of democracies across the world continues to grow. But to be truly effective, democracies need to focus on expanding diversity in their representative structures.

The more diverse and inclusive an elected representative body, the better it can ensure that policies are considered with the interests of multiple communities in mind—irrespective of their ethnicity, religion, sexual or gender orientation, caste, income level, sex, or other axis of exclusion (see here and here). With increased diversity, organizations can also achieve greater equality in access to services, benefits, decision-making, and opportunities in human endowments and economic advancement.

Historically, women have been underrepresented at most levels of government, including in one of the highest bodies of national government: parliament. Over the past quarter of a century, however, the average share of women in parliamentary bodies has been rising in each region. This is a sign of progress, although the global average share of women remains capped at less than one-third of parliamentarians.

In almost all regions, the average share of female representatives in parliaments has been increasing over the last 20+ years.

The exception to a continuous increase lies in South Asia (SAR), where the average share of female representatives peaked—at around 20%—between 2009 and 2012. As of 2019, it has the second-lowest share among all regions. Whereas some regions, like Sub-Saharan Africa (AFR), have seen fairly steady increases in their average percentage of female parliamentarians, in others the overall progress has been more limited or uneven. East Asia (EAP) took the lead early on, but the average shares across EAP countries have not risen as quickly as they have in other regions. In the Middle East and North Africa (MNA), on the other hand, the average proportion of parliamentary seats held by women increased sharply between 2010 and 2015, but (with the exception of 2013) not enough to overcome its lowest-share status since the beginning of the time period. The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region and Eastern and Central Europe (ECA) have consistently been among the top three regions with the highest average share of female parliamentarians—LAC most often and most recently with the highest.

Why does this matter? A growing body of research suggests that among elected officials, women are more likely than men to support policies that help close gender gaps. In fact, countries with a higher share of women representatives at national and subnational levels of government have more laws that equalize opportunities and benefits between women and men, girls and boys in society and economy (see, for example, here and here).

Efforts to improve gender equality include passing laws that aim to close gender gaps in economic empowerment—for example, in paid work and asset ownership—by protecting and supporting women’s participation in the workplace and their rights over family property. These laws help correct systemic gender inequality that is perpetuated by long-standing, patriarchal social norms, wherein male family members are the breadwinners who generate and control household income and assets. Female family members, on the other hand, are relegated to the private sphere of the household, where they shoulder family care and domestic responsibilities. Select regional studies have found the extent of female representation in parliament to be positively associated with parental leave policies and, more broadly, with women’s equality in the workplace (see here and here).

Using the World Bank Gender Data Portal, we explore cross-country and cross-regional patterns between the percentage of women in national parliament and several indicators related to economic empowerment from the Women, Business and the Law database.

Higher representation of women in parliament is correlated with laws to protect women from sexual harassment in the workplace

One way in which legal frameworks can promote women’s paid work is to protect them from sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence in the workplace. Lack of protection from such harassment in the workplace limits women’s job opportunities. In industries with a high reported incidence of harassment, such as the textile industry in Bangladesh, women—in part under pressure of families—may opt out of employment, although the industry offers more job opportunities for women than most other industries.

For each region, by taking the average share of parliamentary seats held by women in countries that do have legislation against sexual harassment in employment—and comparing that to the average share of seats held by women in countries without such legislation—we see that having anti-harassment legislation in a country is correlated with at least slightly higher average shares of female parliamentarians. South Asia is the only region in which all countries have anti-harassment legislation, regardless of the average share of parliamentary seats held by women.

Some countries take further legal recourse against sexual harassment in employment by instituting criminal penalties or civil remedies for it. With the exception of South Asia, having these penalties is correlated with higher regional averages of national parliamentary seats held by women. Like many nations, South Asian countries exhibit a gap between the existence of anti-harassment laws, on the one hand, and additional measures that help implement and enforce these laws, on the other.

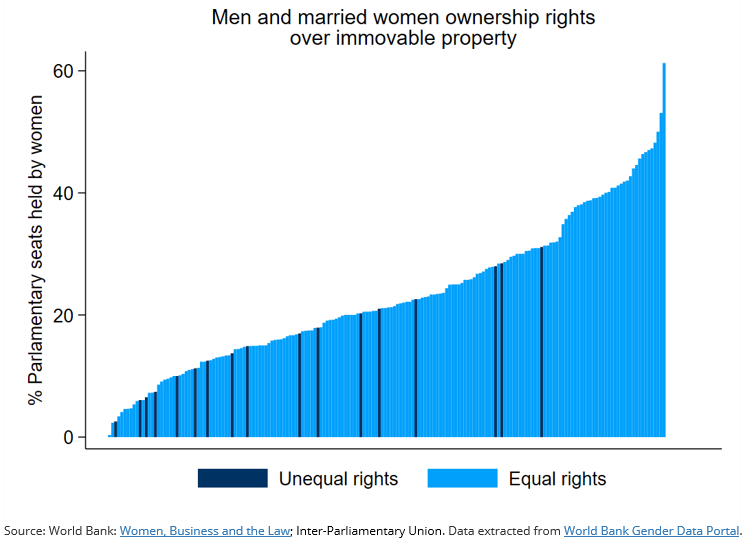

Countries with more women in parliament are more likely to have gender-equal inheritance and property ownership laws

In many developing countries, men tend to own and inherit property and other high-value assets at far higher rates than women do (see here)—particularly in the case of married women, who are more likely than married men to have left their natal home (see here and here, for example). Patrilineal inheritance, a customary practice that ensures family property passes down the male line, is a common feature of patriarchal systems that consolidates wealth and power among by males by kinship or clan. Countries with laws that challenge these age-old, gender-biased norms about property ownership tend to have larger proportions of parliament seats held by women than countries without them.

Greater female representation in parliament also is correlated with the existence of laws that equalize the rights of sons and daughters to inherit family property. Affirming equal inheritance between household males and females, regardless of their marital status, helps close gender gaps in asset ownership. A concern, however, is that many laws may not be enforced or entrenched social norms may override legislation that seeks to close gender gaps.

Still, our observations suggest a potentially positive relationship, a virtuous cycle, between female representation in parliament and some aspects of women’s economic empowerment. Electing more women into democracies may reduce gender gaps in paid work and asset ownership. Conversely, an environment in which more women are breadwinners and property owners may encourage more women to pursue elected positions (and more people to vote for them). Identifying a causal relationship between the two—the direction of the virtuous cycle—requires a more complex and deeper analysis, which future research can explore using the data provided by the World Bank Gender Data Portal.

Join the Conversation