Most streets in Europe are named after people – unlike in most cities in the United States, “where the streets have no name,” at least according to the homonymous pop song. But European streets are named overwhelmingly after men, reflecting how gender biases have been deeply imbedded in European societies for hundreds of years. Are these biases against gender equality pervasive in other regions as well? And is it possible to quantify them and see how they evolve?

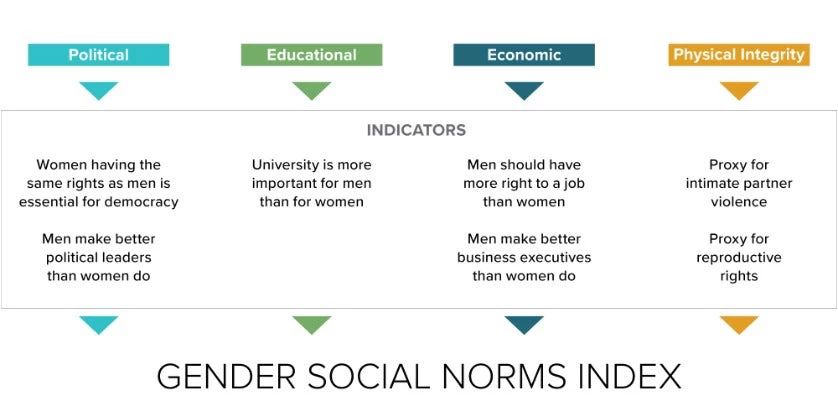

To address these questions, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2019 Human Development Report (HDR) introduced a Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI), whose latest estimates were issued earlier this summer. The GSNI is based on representative survey data from the World Values Survey, reflecting biased gender beliefs, like answering “yes” to questions such as “do men make better political leaders than women do?” The GSNI considers 4 dimensions: political, educational, economic, and physical integrity (figure 1).

Figure 1- Dimensions and indicators of the Gender Social Norms Index

Source: UNDP. 2023. Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

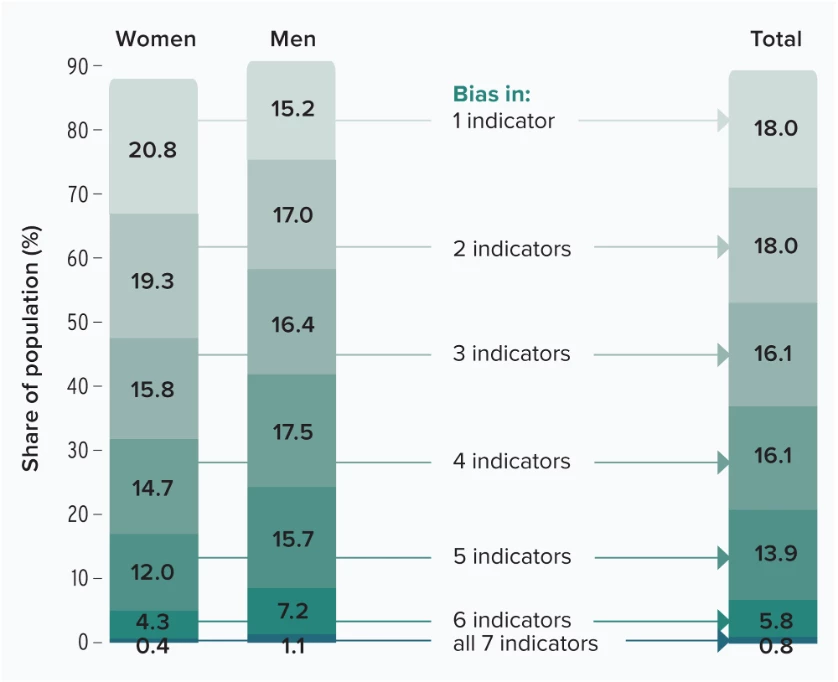

What do the latest results reveal? Shockingly, in 80 countries and territories accounting for 85 percent of the global population about 90 percent of people harbor at least one bias against gender equality (figure 2). And there is no substantial difference in these biases between women and men, reflecting their deeply entrenched social nature.

Figure 2- About 90 percent of people have at least one bias based on the indicators used to construct the Gender Social Norms Index

Note: Based on 80 countries and territories with data from wave 6 (2010–2014) or wave 7 (2017–2022) of the World Values Survey, accounting for 85 percent of the global population.

Source: UNDP. 2023. Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

Gender social norms matter because they can drive the persistence of discriminatory practices against women, even when there are legal protections prohibiting these practices. For instance, a widely studied case was the initial limited impact of two landmark pieces of gender equality legislation in the United States (the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). After these laws were enacted, average gender pay disparities did not immediately narrow in part because firms, at least initially, chose to hire fewer women.

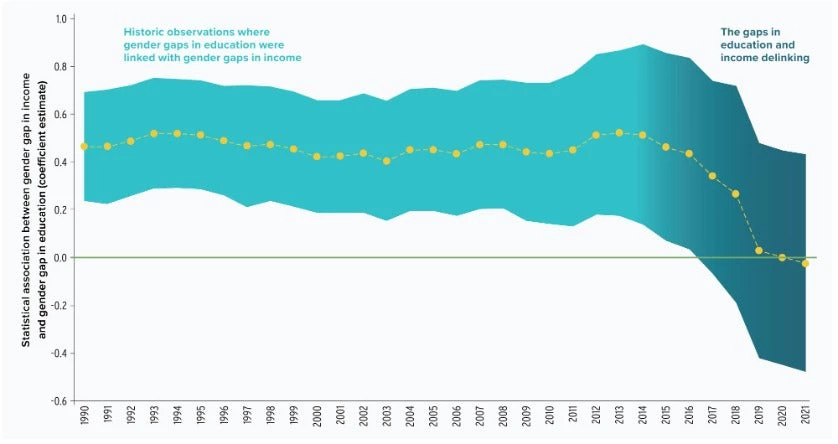

Along with legal protections, measures aimed at reducing gender equalities include enabling women to have greater control over assets or reducing gaps in education. Indeed, historically there was a link between gender education gaps and income gaps, but that association has weakened (figure 3): even though women are often as or more educated than men today, gender income gaps persist.

Figure 3- Association between gender gaps in education and gender gaps in income has weakened

Note: Each dot shows coefficient estimate in a linear regression model of gender gaps in income on gender gaps in education across countries. The vertical lines above and below the dots represent the 95 percent confidence interval.

Source: UNDP. 2023. Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

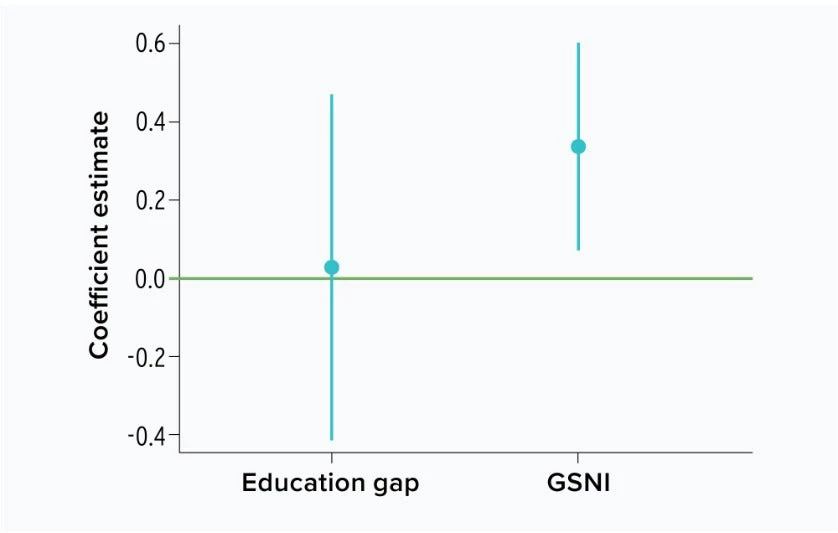

While regressing gender gaps in income on gender gaps in education is now close to zero, regressing gender gaps on income with the (GSNI) shows a statistically significant positive coefficient (figure 4).

Figure 4- Biased social norms still account for gender gaps in income

Note: The figure shows the estimated coefficients of a model regressing gender gaps in income on gender gaps in education and on Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI) values using the latest year of data in tables A1 and A4. The vertical lines above and below the dots represent the 95 percent confidence interval.

Source: UNDP. 2023. Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

Biased social norms impair women’s rights with consequences ranging from worse academic achievement than men (sometimes because gender-neutral language is not used in exams) to worse mental health and wellbeing (with structural gender inequalities potentially becoming biologically embedded as a result of cumulative and iterative processes of adverse experiences). This manifest injustice is certainly the main reason we need to eliminate biased social norms, but it is also important to recognize that gender inequalities make everyone worse off. For instance, recent evidence shows that gender-diverse teams produce more novel and higher-impact scientific ideas. And the GSNI was used to show an association between gender biased social norms and higher population-wide cardiovascular disease mortality rates.

Therefore, the effort to quantify biased social norms is crucial to redress injustice against women and girls, as well as to make our societies as a whole better off. It is shocking that the GSNI shows that about 90 percent of people around the world harbor such biases. Which takes us back to street names in Europe. An organization took the trouble to look at the names of 146,000 streets in 30 major cities across 17 European countries. What did they find? Coincidentally, that around 90 percent of the streets named after individuals are dedicated to men. And one more thing: couples filing joint tax forms in the United States put the male name first almost 90 percent of the time.

Be it in street names, filing tax forms, asset ownership, or composition of decision-making bodies all over the world, unveiling gender biases is only the first – albeit crucial – step to combat disparities. We then need to make sure to use these insights to break down gender biases and shift social norms towards gender equality.

Join the Conversation