The socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 are devastating for migrants and displaced families. Directly and immediately, they are experiencing loss of livelihoods, rising xenophobia, and curtailed access to services besides being largely excluded from recovery efforts. In parallel, millions of ‘children left behind’ are taking the brunt of this fallout as their family members who moved internally or abroad in hopes of sustaining them, cut down on remittances - the lifeline projected to drop by 14 % by the end of 2021.

Even the smallest change in remittance flows can make a huge difference to a child’s life–whether a girl can stay at school, a child goes to bed hungry or a mother can afford to pay for routine vaccination. Yet, we continue to be double blind: when discussing the impact of COVID-19 on remittances, the plight of children dependent on these is not taken into account–and when discussing the impact of COVID-19 on children, rarely do we factor in the importance of remittances.

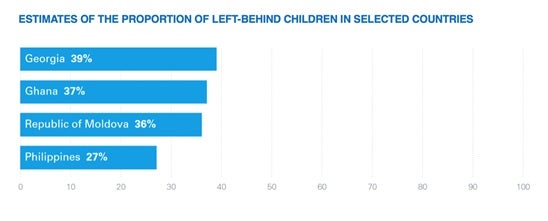

How exactly does this drastic decline in remittances affect children? To begin to grasp what this means, note that 800 million family members–about one in every nine people worldwide–receive remittances. Whilst the number of children receiving remittances is not precisely known, in some countries, one or both parents of more than 30% of all children have migrated.

Not only families, but many countries depend on remittances. For at least 57 countries, remittances represent 5 % or more of GDP and for 10 countries remittances stand at more than 20 % of GDP. With their potential to finance trade balances, act as a source of tax revenue and advance economic growth, remittances can often cushion the impact of economic shocks, allowing governments to continue spending on education, health and other sectors that matter for children.

At the household level, beyond immediately augmenting income and lifting families out of poverty, remittances also have more lasting benefits for the welfare of children, improving access to education, diminishing child labour, improving nutrition and boosting health care access. In fact, 75% of remittances are spent on essentials, including food, school fees, medical expenses and housing. An analysis of studies conducted in 30 countries finds that on average, international remittances increase education expenditure by 35%, in Latin America and the Caribbean this stands at 53%. Now with COVID-19, we witness and expect to see the flipside of this: children left behind are dropping out of school, their mental health and wellbeing are worsening, they are having to skip meals, are at a greater risk of child marriage and child labour and are facing more household responsibilities, especially as they may be left with elderly relatives who are at the highest risk of COVID-19 and need to be cared for themselves.

In Moldova, for example, where child poverty is at 11.5% and 36% of children are estimated to be left behind, remittances make up 16% of GDP and have decreased by 25%. We find that in 30% of remittance-receiving households with children, children’s nutrition is impacted as households cut down on the number of meals or their nutritional value. IOM and WFP reinforce these findings with an estimate that at least 33 million additional people could be driven into hunger by the end of 2021 due to the expected drop in remittances alone.

Families left behind often find themselves with no recourse to relief measures as these often target workers in the local economy, or do not take into account the ‘new poor’. Similarly, migrants are at risk of being doubly excluded from the socioeconomic response to COVID-19–being absent from their home country and all too often ineligible for social protection in their host country.

It doesn’t have to be this way. There are four interconnected policy areas which can mitigate these far-reaching impacts. In many countries, some of these policies are already in place and have helped dampen the risks to children.

First: Support for migrant workers, including:

• emergency social protection responses to COVID-19 that are inclusive of all migrant workers

• access to health care and essential services as well as adequate remuneration, working and living conditions for all migrants.

Second: Measures to keep remittances flowing, including:

• declaring the sending and receiving of remittances an essential service and maintaining flows, even during lockdown.

• expanding technological solutions to help ease the flow of remittances and supporting migrants and remittance-receiving families wishing to use them.

• reducing costs of sending remittances, to achieve the SDG target for transaction costs of less than 3% of the remittance value.

Third: Support for remittance-receiving households, including:

• social protection responses that are inclusive of remittance-receiving households through revising eligibility criteria and allowing more flexibility for changes in circumstances

• facilitating the reintegration of returnees to minimize burdens on their families and communities. Returnees should also be supported if they decide to emigrate again, to minimize the likelihood of their exploitation.

• addressing the specific barriers experienced by left-behind children in accessing key services through targeted support.

Fourth: International cooperation, including:

• taking into account how declining remittances affect child well-being when monitoring the impacts of COVID-19 on economies and financing socio-economic recovery measures.

• developing transnational social protection schemes, so that children and their families don’t fall through the cracks in future crises.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Further reading:

• Discover more about how children are affected by the COVID-19 decline in remittances

• Read the UNICEF Technical Note on ‘Social Protection for children and families in the context of migration and displacement’

• Discover more about how UNICEF is responding to the COVID-19 crisis through social protection

• Browse through UNICEF-led and supported COVID-19 socio-economic impact assessments and child poverty analyses

Join the Conversation