Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in Project Finance International. A version is reprinted here with their permission.

“How can we as government make the best use of our external advisers?” This is a question we often hear as regular advisers to host governments, or from multilateral or other agencies supporting governments, on the procurement of much needed energy and infrastructure—especially in emerging markets.

Thankfully, this question now comes up more often at the earlier end of the project procurement, rather than near the end.

In other words, the capacity building for public sector procurement that donors have funded over the past decade is paying off.

However, there is still some way to go before public sector entities derive the most out of external advisers – whether it be technical, financial, legal, insurance, industry specialist or similar advisory support. When ministries or other agencies decide to procure a new power plant, road, water treatment/distribution network or similar long-term infrastructure asset, it is usually preceded by a reasonably complete feasibility assessment, often including an “options analysis” in terms of methodology of procurement and the possible role of the private sector.

At that stage, the relevant executing agency ought to have appointed some external advisers –technical, financial, or legal – to assist the initial feasibility study. Ideally, governments appoint advisers with strong track records and reputations so the study produced is accurate and robust for review by private sector investors, as well as to add weight to the seriousness with which the project is viewed by the relevant government.

The study should also withstand a reasonable period of time in terms of estimated costs and other financials, in anticipation of lengthy processes for government and budgetary approvals. Delays can sometimes arise if the subsequent implementation of the project renders the previously accepted affordability envelope contained in the feasibility study as redundant, and fresh estimates are called for.

Then considerations for private sector involvement will start to be weighed: will it be a joint public-private sector procurement of an asset plus associated services/operations (such as a PPP) or will it be something less than that – perhaps involving only outsourcing, construction, or technical assistance?

Here, government counterparts will need advice that allows them to evaluate and calculate, on a comparative basis, what may be the optimal outcomes for the project. Other factors may come into play too, such as any unique design related issues, “newness” of any special technology, or whole life costing. Again, governments should maximize the prior experience of appointed advisers.

Government agencies will also need to factor in best practices arising from local custom and interpretation of regulation and laws, not only for themselves but also for their potential impact on the appetite of investors and on the form and manner of the procurement process. For instance, in some parts of Asia, obtaining sufficient clarity up-front and seeing the risks related to, for example, land use rights, mining rights, water abstraction rights, or building approvals, can be deal-breakers for potential investors.

Securing true value for taxpayers’ money is what is at stake, and achieved best through the intelligent use and appointment of experts.

How are advisers appointed?

Typically, governments run competitive tenders for the role of technical, commercial, legal or insurance advisers. Often those tenders require various advisers to join together as a consortium – with a prime contractor taking a lead role and others providing inputs as sub-contractors. For many executing agencies, this saves time. It is usually impossible, however, for each adviser to take on financial or performance exposure for the work of the other consortium members. This is why it is not advisable for governments to attempt to procure consortium members on a *joint and several basis.

Best practice for the appointment of advisers is to identify a thorough scope of work, timeline, specific deliverables – which should mirror payment milestones – with flexibility built in to accommodate changes or additions that arise during project implementation. Fees will likely be fixed, for practical purposes. Often governments will choose the cheapest option, even where the costs are “covered” by a third party, such as a regional development bank. Experience has shown time and again that one gets what they pay for; this may mean an incomplete or poorly structured tender that lacks solutions for key risk items, fails to address common bankability considerations, and/or leaves out important components.

When governments fail to realize what they are missing – and can gain – from advisers, projects can go astray.

The easiest way to bring best practices to the forefront is through regular deal flow. Absent that, continued capacity building will be key.

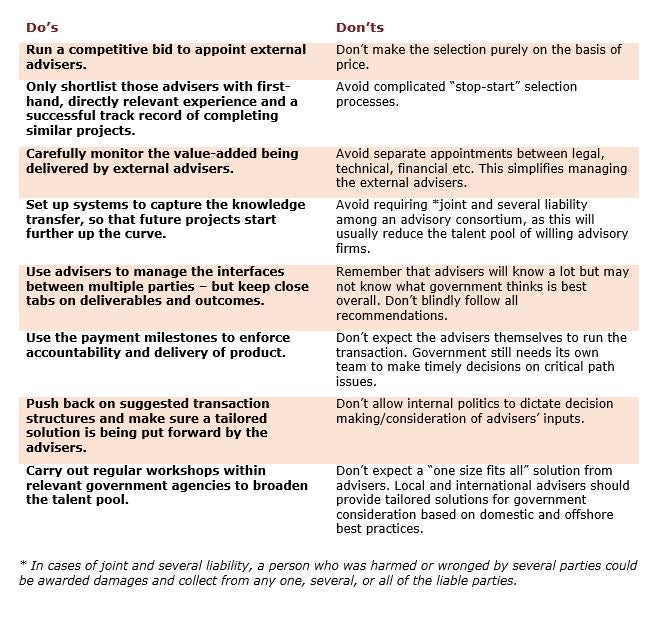

This table identifies best practices in terms of what to do and what to avoid in appointing and utilizing external advisers.

The ambit of best practices to better utilizing external advisers is broad. The essence is: make sure real value is provided, and require accountability and flexibility at the same time as incrementally learning from each engagement. This applies across industries and all sectors, both public and private.

Disclaimers: The views and opinions set forth herein are the personal views or opinions of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect views or opinions of the law firm with which they are associated. The content of this blog does not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank Group, its Board of Executive Directors, staff or the governments it represents. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data, findings, or analysis in this post.

Join the Conversation