What are the benefits of the All-Asset Security Right? | © NicoElNino, Shutterstock

What are the benefits of the All-Asset Security Right? | © NicoElNino, Shutterstock

From satellites to power plants, bridges to airports, infrastructure is often project financed—that is, financed on the security of a project’s revenue streams and assets. A common structure for such projects is the creation of a legally independent entity, a special purpose vehicle, to isolate financial risk—including insolvency. Project finance can be contrasted with asset-based financing, which is structured around assets alone.

The World Bank Group along with other development institutions are no stranger to project financing: ongoing projects we’re involved in include the Dar es Salaam Maritime Gateway Project, the Pacific Regional Connectivity Program Project for Fiji, the West Africa Regional Communications Infrastructure Project, or the Ivato and Fascene Airports in Madagascar. However, compared to asset-based financing, implementing a project financing scheme is a particularly complicated, costly, and time-consuming operation. It often involves a small army of lawyers, bankers, engineers, insurance brokers, and other experts.

But, at its core, project finance is little more than a complex secured transaction—both structures are but two sides of the same secured financing coin. It follows that project finance, like asset-based finance, can be facilitated by a modern secured transactions legal regime.

The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law’s (UNCITRAL) Model Law on Secured Transactions (we call this the “Model Law”) provides the international best practice template for such a regime. The Model Law and domestic laws based on it are usually viewed as benefitting asset-based financing. But their benefits extend further. To this end, this blog looks at a key concept from the Model Law: the “all-asset security right.”

All-asset security rights

There are two key aspects of an all-asset security right:

- First, it captures all present and future assets of the grantor in a single security device

- Second, the grantor has the right to dispose of some encumbered assets (such as inventory) in the ordinary course of business

The breadth of this security right has significant utility for project financiers. This is because project financing is usually provided to a dedicated project company. This company will be legally and financially separate from the entity that initiates the project – the “sponsor.” Generally, there will be limited or no recourse to the sponsor. In most cases, this leaves the lender to look to the project company, its assets, and its cash flow, for its primary security. Accordingly, an essential task for the lender’s lawyer is to ensure that the lender’s security package captures all these diverse assets.

This task is often complicated by the incredible variety of ways that a lender can take security—each of which usually has its own formalities, benefits, and limitations often envisaged in separate laws (one per type of encumbered asset), as well as with disparate registries for registration of each kind—or group—of assets. The result is that, in jurisdictions that do not recognize all-asset security rights, a single project financing transaction will involve an incredible assortment of different security devices, all applying to different bits and pieces of the project company’s assets.

Benefits of a statutory all-asset security right

The all-asset security right expands on the security devices that have long been relied upon by project financiers worldwide—such as the “floating charge” or the “enterprise mortgage”—in three ways:

- First, an all-asset security right typically has a broader scope of coverage than its pre-Model Law equivalents. This is because the security scope is defined legislatively and uniformly under the Model Law, rather than relying on a patchwork of precedents and industry practices.

- Second, an all-asset security right can automatically attach to the full range of proceeds arising from the disposal or destruction of the assets, rather than just those proceeds that may be foreseen by the parties and recorded in the security agreement.

- Third, an all-asset security right provides greater clarity and transparency for project financiers because the Model Law provides for the public registration of all security rights—not just those that fit within pre-defined categories of registrable security rights (as is often the case in common law jurisdictions).

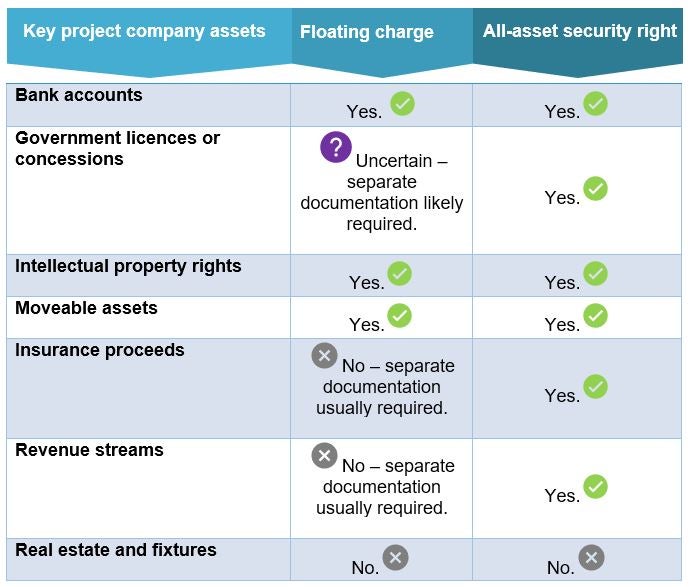

Bringing the above together, we can see that while a project financier may have previously taken a floating charge over all the project company’s assets, an all-asset security right will provide specific benefits. Some of these are summarized in the table below:

A project financier can use an all-asset security right to capture the vast majority of a project company’s assets using a single security device. This strengthens and streamlines the legal assemblage required for the project financier’s comprehensive security package.

Realizing the benefits of the all-asset security right contributes to a broader understanding of the critical role that modern secured transaction regimes can play in infrastructure financing, regardless of the particular financing structure employed and the perceived barriers between these structures.

*The authors are indebted to Professor Ignacio Tirado, Secretary General of UNIDROIT and Professor Teresa Rodríguez de las Heras Ballell, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid for their excellent suggestions and thoughtful contributions to improve the content of this blog.

Disclaimer: The content of this blog does not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank Group, its Board of Executive Directors, staff, or the governments it represents. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data, findings, or analysis in this post.

Join the Conversation