Cites are the heartbeat of the global economy. More than half the world’s population now resides in metropolitan areas, making a disproportionate contribution to their respective countries’ prosperity. The opportunities and challenges associated with urbanization are quite evident in the world’s most populous country, whose cities are among the largest and most dynamic on Earth. To better understand what a thriving metropolitan economy looks like in the Chinese context, our Competitive Cities team selected Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province, for inclusion among our six case studies of economically successful cities, as the representative of the East Asia Pacific Region.

As recently as the turn of the millennium, Changsha’s economy was still dominated by low-value-added, non-tradable services (e.g. restaurants and hair salons) – an economic structure commonly seen today in many low- to lower-middle-income cities. Since then, Changsha has achieved consistently high, double-digit annual growth in output and employment, despite its landlocked location and few natural or inherited advantages, such as proximity to trade routes or mineral wealth. With per capita GDP surging from US $3,500 in 2000 to more than US $15,000 in 2012, Changsha has accomplished a feat so many other World Bank clients can only dream of: leapfrogging from lower-middle-income to high-income status in barely a decade, and an economy now comprised of much more sophisticated, capital-intensive industries.

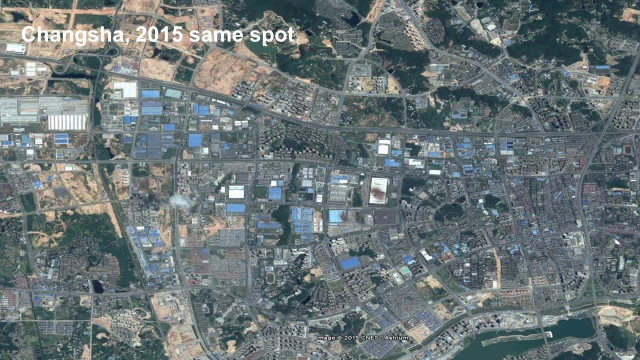

Photos via Google Maps

We took a closer look at the success factors behind this city’s dramatic growth story, and what lessons its experience may hold for cities elsewhere, especially in terms of (1) how to overcome coordination failures and bureaucrats working in silos and (2) how to ensure a level playing field for all firms in the city (that is to say, competition neutrality), even in industries with a strong SOE presence – something still not commonly seen in China these days.

Changsha’s (and Hunan’s) growth has clearly benefitted from a highly conducive national macroeconomic and policy framework, including a plan entitled The Rise of Central China, aimed at spurring development in areas beyond the country’s booming coastal regions. This and other initiatives provided for the removal of investment restrictions, more favorable tax treatment, and enhanced infrastructure and connectivity to coastal commercial gateways. China’s massive stimulus plan in 2009 (in response to the global financial crisis and recession) jump-started construction activity in the country, providing further impetus to one of Changsha’s principal industries, construction machinery and equipment manufacturing. And national government interventions in earlier decades – especially the establishment of dedicated research institutes – provided a critical contribution to Changsha’s accumulation of expertise in such disciplines as machinery or metallurgy.

Notwithstanding these national initiatives, responsibility for local economic development in China is highly decentralized, with municipal government leaders directly tasked with achieving GDP growth and tax revenue targets. Municipal governments also have rights over almost all land in cities, which can be leased or used as collateral to fund local infrastructure. In Changsha, municipal authorities used these prerogatives to improve their city’s economic competitiveness.

Changsha’s authorities have striven to balance the growth of existing industries in the city (e.g. construction machinery) with the attraction and development of emerging ones (e.g. automotive and media/entertainment). Sector-specific forms of support have included the provision of market intelligence, support for R&D, and dedicated worker-training programs. Notably, fierce local competition among Changsha’s incumbent firms, regardless of ownership status, has been encouraged as a necessary ingredient for their international competitiveness. At the same time, the city was not reluctant to let go of uncompetitive industries, especially those requiring permanent subsidies to keep operating. The increasing diversification of Changsha’s economy has reduced its vulnerability to cyclical downturns afflicting individual industries, and has buttressed municipal fiscal revenues.

Changsha has managed to avoid some typical pitfalls, such as bureaucrats working in silos, turf battles and coordination failures often seen in other cities, by using inter-agency coordination mechanisms called “leading groups.” In terms of pro-active economic development efforts, the leading groups help coordinate investment-attraction and investor-aftercare activities across various functional departments and tiers of government, providing for clear roles, processes, reporting requirements and accountabilities among them. They seem to work well in practice for two main reasons: (1) Targets, rewards and incentives are aligned across all levels of agencies (city, district and industrial zone); and (2) Only problems are escalated to higher government levels, which helps avoid many of the problems typically arising from having to “go through the bureaucratic process” and, in turn, ensures that this will not amount to yet another failed coordination mechanism.

Changsha’s municipal leaders are particularly aware of the role that human capital plays in economic competitiveness and raising incomes, developing a two-pronged approach to its improvement. On the one hand, the city sought to attract new talent to the city, through programs to identify, recruit and appropriately compensate highly skilled individuals from both China and abroad. On the other hand, Changsha strove to upgrade the skills of its existing talent through targeted vocational degree programs and through the systematic development of specialized in-demand skillsets.

The Changsha case study is the fifth in a series of six reports on economically successful cities, one from each world region, produced by the World Bank’s team with funding from the Competitive Industries and Innovation Program (CIIP), and published in late 2015[1]. These reports provide a more detailed account of exactly what each city did to achieve the success that it has, and how it went about doing so.

“Competitive Cities for Jobs and Growth” has been made possible by the contribution of the Competitive Industries and Innovation Program (CIIP). The overview report and companion papers were launched in Washington in December 2015, and a number of regional events will be held throughout this year. The report will be launched in Asia in March 2016 at the Urban Roundtable in Singapore, an event co-organized by the World Bank Group and the Centre for Liveable Cities.

Join the Conversation