Dar es Salaam Port, Tanzania

Dar es Salaam Port, Tanzania

Part II. Lead Firms of Global Value Chains Continue to Make Agile Adjustments

This blog is part two of a 3-part series on the way in which global value chains are affected by COVID-19.

Part I. Multinational corporations and their suppliers are being hit hard

Part III: Governments should prepare for the ‘new normal’ in global value chains – here is how

The devastating impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) on global value chains (GVCs) is unprecedented, but disruptions from crises are not new. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the 2011 Japanese earthquake, and the 2011 Thailand Chao Phraya river floods each shaped the evolution of GVCs, in many ways making them more resilient. Agile adjustment is a main characteristic of lead firms within GVCs, and reshoring is not the only strategy for building more resilience.

As the architects of GVCs, multinational corporations constantly adapt to risks and opportunities by reconfiguring production networks and optimizing supply chain complexity. They strategize to improve not only efficiency, but also resilience. Their strategies take into account technological advancements, shifting consumer preferences and government policies. For example, asset-light models of investment and automation-driven reshoring had been underway long before the crisis.

No consensus has emerged on how GVCs will look after COVID-19 subsides. Some economists hold the view that there will be little significant change and that adjustments will concentrate in health-related industries, as the economic rationale for most GVCs continues to hold. Others believe that COVID-19 has become a wake-up call for a new balance between risk and reward for GVCs, as pandemics, climate change, natural disasters and manmade crises may expose the world to more frequent crises. Further, the pandemic has exacerbated protectionist sentiments, calling for shortening of supply chains and greater self-sufficiency.

Diversification of suppliers has been a key strategy of multinationals to mitigate risks. Given the changed risk appetite as a result of the pandemic, some will be willing to lose some efficiency gains to diversify suppliers, including from certain countries. Some companies may choose to reshore their production, diversify their operational locations, or hold more inventories. Indian automotive manufacturing companies such as Tata Motors and Maruti, for example, are increasing local sourcing to reduce their dependence on China. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest contract integrated circuit manufacturer, announced it will invest $12 billion to build an advanced semiconductor fabrication plant in Arizona.

Just how massive will localization or relocation of production be?

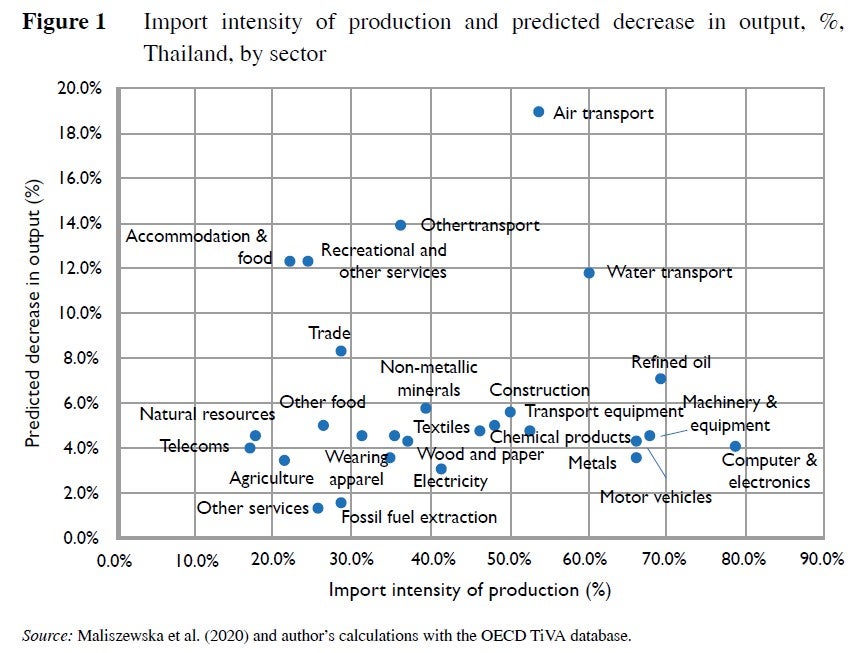

Consider two facts. First, the relationship between production length and GVC resilience is more complicated than it looks. There is no correlation between supply chain complexity and the severity of the economic impact of COVID-19 (figure 1). Production localization, or shorter supply chains, would not necessarily be less vulnerable. On the contrary, some previous crises and disasters we mentioned earlier led to more offshoring to diversify suppliers and a production network across different countries. Even during COVID-19, countries have still relied on the global production network to meet sharp rising domestic demand of essential medical goods. For example, before the crisis, China produced around 20 million face masks per day, roughly half of global production. By early March 2020, this had been ramped up more than six-fold, to 120 million per day, mostly for export.

Figure 1. No clear relationship between GVC complexity and severity of COVID-19 impact

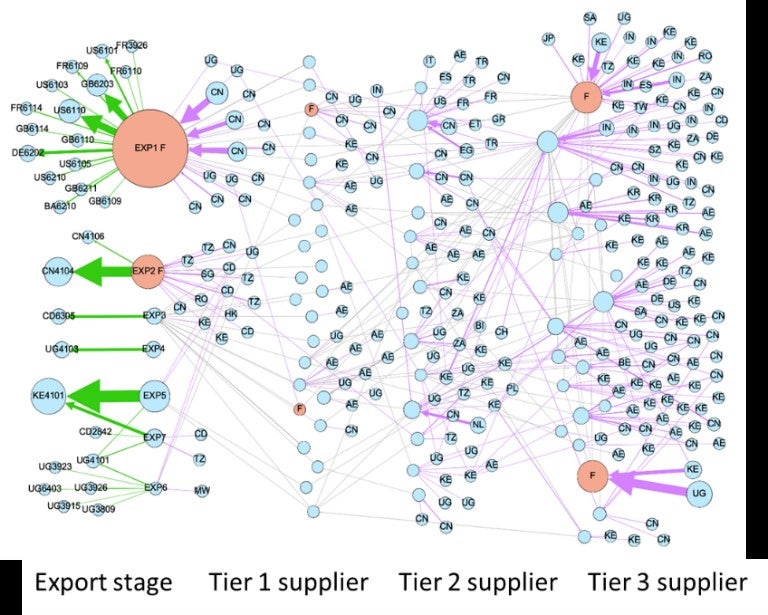

Second, traditional supply chains have transformed over time into supply networks. This makes it difficult to relocate, whether back to one’s own country or to another country. The challenge lies in a combination of how modern supply networks are structured and how lead firms choose to engage with their suppliers. For example, a foreign affiliate manufacturing T-shirts in Rwanda sources coloring material, textiles, and machinery from at least three tiers of domestic suppliers, while importing chemicals and machines from hundreds of firms around the world (figure 2). As the example shows, the supplier networks are so interconnected that building them somewhere else would incur costs and take time, and thus risk losing competitive positioning. Even if production facilities can be relocated, it would require a whole ecosystem of talent pool, good infrastructure, and nearby upstream/downstream industries to scale up production in a new location.

Figure 2. Rwanda’s garment & leather value chain

Geopolitical situations and financial incentives offered by some governments may tilt investors’ decisions on where to operate. U.S lawmakers and officials are crafting proposals to push American companies to move operations or key suppliers out of China by offering tax breaks, new rules, and carefully structured subsidies. Japan has set aside a record $2.2 billion support package to subsidize manufacturers who move their production out of China. The consumer products maker Iris Ohyama is the first in line to take advantage of this subsidy.

As lead firms seek to stay abreast of the evolution of GVCs in the recovery phase, one sure strategy for multinationals is to use digitalization to optimize supply chain management. To withstand disruptions due to crises, multinationals’ strategy is not to simplify the network that exists for efficiency. Rather, they invest in tools to deal with the complexity and to introduce reactivity and flexibility in operations. COVID-19 could be an opportunity to embrace digital transformation efficiency and reduce risks. Multinationals can use AI, machine learning, and Big Data to monitor a producer’s entire supply network and can use ICT advances to remotely plan, develop and oversee production, connect to customers, and fulfill orders (figure 3).

Toyota has efficiently implemented this approach since the 2011 Japanese earthquake, allowing it to track components and replace them easily during COVID-19. About 70 percent of executives in Europe are speeding up digital transformation due to the pandemic, with banks, health care providers, and retailers moving to digital channels and using e-commerce platforms to expand their customer base (MGI, 2020). For example, hello-lisa.com has allowed livestream shopping to create a bridge between closed shops and consumers at home.

Figure 3. From supply chain to supply networks

Supporting suppliers is another critical way to create resilient production networks, as multinationals increasingly recognize that suppliers are their intricately linked partners. Lead firms can accelerate payment for goods that have either been produced, or are in the process of being produced, as shown by global garment retailers, and by suppliers of Boeing airplanes. Multinationals can also help suppliers adapt their production process to a different market after COVID-19. For example, Apple is helping their partners redesign and reconfigure factory floorplans to maximize interpersonal space. Evidence suggests that long-term relationships among companies are associated with a more rapid recovery (Jain et al., 2016).

Join the Conversation