Drone aerial view of deforestation in the amazon rainforest. Trees cut and burned on an illegal dirt road to open land for agriculture and livestock in the Jamanxim National Forest, Para, Brazil.

Drone aerial view of deforestation in the amazon rainforest. Trees cut and burned on an illegal dirt road to open land for agriculture and livestock in the Jamanxim National Forest, Para, Brazil.

Recent deforestation alerts suggest that forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon is slowing. This is good news – but also not entirely surprising. Economic models are becoming increasingly able to foretell the direction of deforestation.

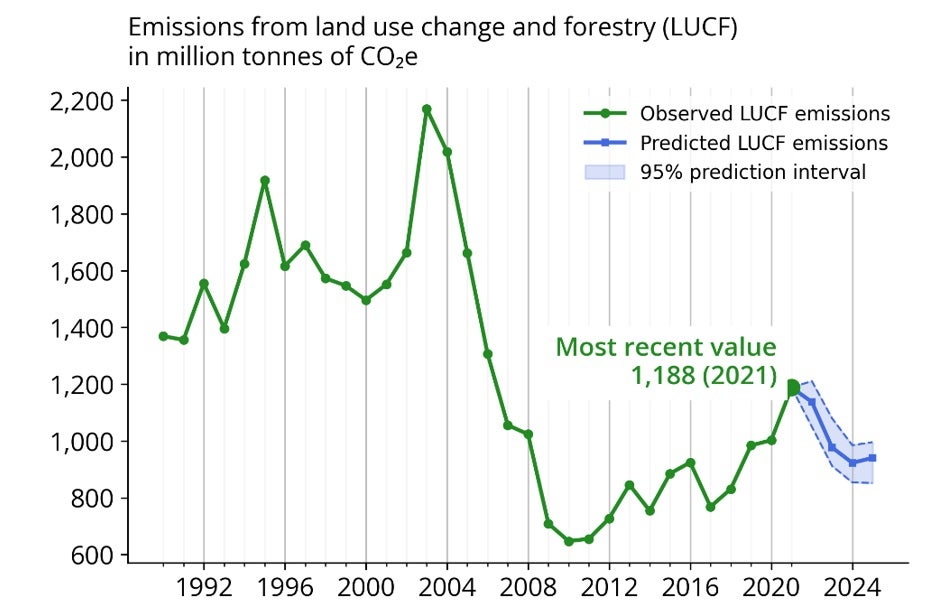

In April 2023, we published our projections for Brazil’s Land Use Change and Forestry (LUCF) emissions based on a new macroeconomic model (Figure 1). Back then, we only had official deforestation data until 2021. Nevertheless, the model predicted falling LUCF emissions for 2023 which is consistent with the easing deforestation pressures in the “arc of deforestation” we are now witnessing. Almost all LUCF emissions in Brazil are due to deforestation, so trends in LUCF emissions follow trends in deforestation very closely (Figure 2). Notably, the model had also correctly predicted the trend reversal in 2022, where deforestation slightly declined for the first time after four years of consistent increases.

Identifying such trend reversals early on is crucial for helping policymakers target their efforts to reduce deforestation and associated emissions. Accurate predictions also support development of sustainability-linked financing instruments for allocating private and public capital to strengthen forest protection systems. Recent research into Brazilian REDD+ projects has highlighted that without accurately accounting for baseline deforestation trends, instruments, such as carbon offsets, can severely misrepresent avoided deforestation.

Figure 1: Land use change and forestry emissions based on economic projections using historical data until 2021.

What’s the story behind this projection?

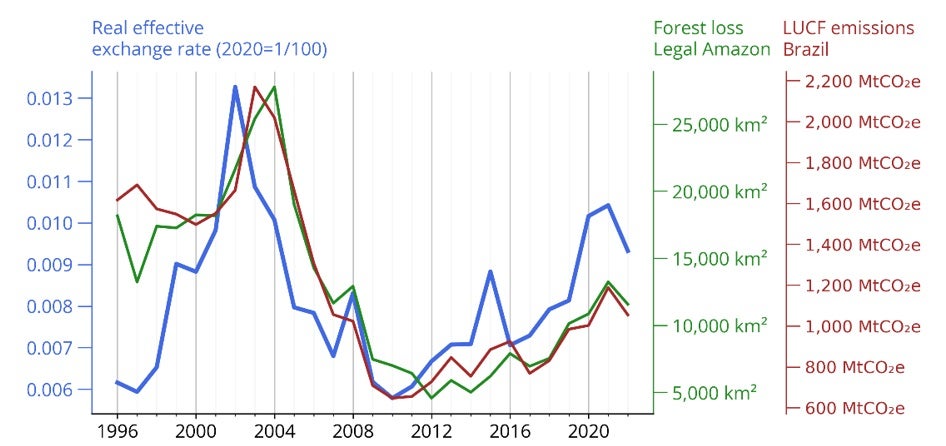

Our recent Amazon Economic Memorandum tells the story behind the projections in Figure 1. The economy strongly influences land use choices in Brazil. It is well known that higher commodity prices lead to increased deforestation in the Legal Amazon, as the demand for land to produce those commodities increases. What is less well known is that other prices also matter. Our modeling suggests that the most important variable correlating with Amazonian deforestation and Brazilian land use change and forestry emissions is Brazil’s real effective exchange rate (REER), i.e. Brazil’s exchange rate weighted for price differentials across its trading partners.

The REER is a measure of Brazil’s external competitiveness. Since agriculture is Brazil’s most important export, a depreciating REER increases the competitiveness of export agriculture, fuels demand for land, and thus increases deforestation. This relationship is historically very strong: the REER predicts deforestation in the Legal Amazon roughly one year in advance (Figure 2).

Combining the REER and a commodities price index allows our model to explain about 93.7% of the variance deforestation and 91.1% of the variance of Brazil’s LUCF emissions between 1998/99 and 2021. Despite relatively elevated commodities prices, deforestation is currently decelerating due to an appreciating REER associated with factors like Brazil’s post-Covid 19 economic rebound and tight monetary policy to fight inflation. Between May 2021 and May 2023 (latest data available) Brazil’s REER has appreciated by 17%. On average, when the REER appreciates by 1%, deforestation in the Legal Amazon falls by 1.13% in the following year.

Figure 2: Brazil’s real effective exchange rate and deforestation in the Legal Amazon

The historical relationship allows us to make one-year deforestation forecasts with reasonable accuracy. The longer the horizon, the more difficult it is to accurately predict the future. For a longer horizon, we build our deforestation forecasts using the World Bank’s macroeconomic forecasts. Together, such forecasts provide early guidance on the likely direction of economic variables and deforestation.

Long- and short-term measures for economic and environmental policy

Predicting deforestation supports government efforts to make choices about where to put resources for controlling deforestation. Our model predicted a slowdown in deforestation in 2022 due to economic factors only. Still, actual deforestation rates, while lower than in 2021, were about 20 percent higher than our model predicted. This difference is consistent with the weakened governance environment for forest protection in the past years.

In the longer term, we have been arguing that a growth model which decouples the economy from deforestation is highly complementary to forest protection policies, while promoting economic development. Productivity is what ultimately drives the REER, so higher productivity across Brazil would also reduce the long-term economic pressures currently destroying Brazil’s natural forests, which generate at least US$317bn a year in wealth for Brazil and the world.

In the shorter term, sustainability-linked bonds could set strong incentives for governments to act more forcefully to protect forests—but only if we can clearly distinguish how much deforestation was due to outside factors (exchange rates, global commodity prices, weather conditions) and how much was really due to government action or inaction. In other words, what part of deforestation reduction can we credit the government for?

This distinction is crucial for the effectiveness of pay-for-performance type instruments. Both sides of the transaction – the financiers and borrowers – would want to be sure that rewards are only paid out for actual conservation efforts. Governments should neither be rewarded for a slowdown in deforestation if that trend is due to a global drop in beef demand, nor should they be denied well-deserved payments for protecting forests, if unusually hot and dry seasons fueled unprecedented forest fire losses.

The transparency granted by the model is not just critical for sustainability-linked instruments but can help set benchmarks for a broader range of instruments for conservation policy and finance.

Join the Conversation