Accessible sidewalks in Peru

Accessible sidewalks in Peru

Cities are where people come together to chase their dreams, connect with loved ones, and access vital services and opportunities to live better lives. So, it is crucial that people -- regardless of their disability, age, income, or other constraints — can get from one place to another independently, and without challenges. That makes accessible sidewalks vital.

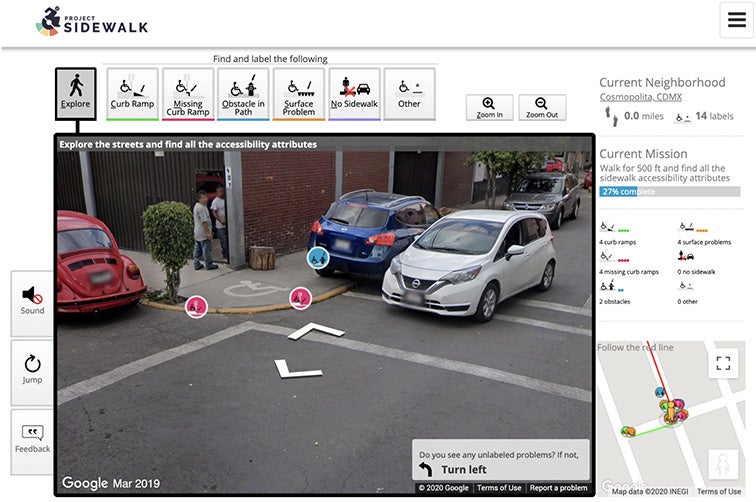

To improve sidewalks so they are functional and accessible for all, Project Sidewalk has an ambitious plan to map and assess the location and condition of every sidewalk in the world, through a process that combines remote crowdsourcing and computer vision.

Inclusive development is a key priority for the World Bank, so naturally, we were curious to learn more about Project Sidewalk and spoke with its co-founder Jon Froehlich to understand their approach.

What are the most common ways in which sidewalks are inaccessible to people with disabilities?

Sidewalk barriers can impact people differently depending on their physical, cognitive, and sensory abilities. For wheelchair users, common problems include the absence of steep street gradients, cross-slopes (sidewalk tilts), surface problems (such as degraded concrete or pavement), and other obstacles. These problems may be temporary – like cars parked on sidewalks, bikeshares blocking access, garbage cans, or more infrastructural and permanent like telephone poles, fire hydrants, and electrical boxes.

For persons who are blind or have low vision, crossing the street can be challenging - curb ramps require tactile surface indicators and pedestrian signals need audio options. Tripping hazards or unexpected barriers that are not easily observed with a cane are also problematic. For others, the lack of appropriate signs and crosswalks can reduce safety or cause confusion.

How do you see accessible sidewalks contributing to more inclusive cities?

Sidewalks play a crucial role in urban mobility and quality of life. Ideally, sidewalks provide a safe space for pedestrians, help interconnect mass transit services, and serve as unique public spaces for food, commerce, and leisure. Without accessible sidewalks and accessible transit, a city excludes where and how people can travel.

How does this work in developing countries?

With our partners, Liga Peatonal, we have begun studying sidewalk conditions and human mobility in developing countries and see that often, concerns for pedestrian safety and well-being intersect with accessibility concerns. In Mexico City, nearly 55% of all fatal vehicular accidents involved a pedestrian. In our preliminary analysis of data on sidewalk conditions in Mexico compared to the United States, we found that curb ramps in Mexico were less common and when they did exist, were rated as less accessible.

Across any municipality, designing and maintaining accessible, safe sidewalks require a complex mix of policy, local and national legislation, resources, and accountability. For example, Mexico City has passed their own local legislation and guidelines that go beyond national policies for sidewalk and transit accessibility.

How has sidewalk accessibility become more urgent, given climate change?

Walking, rolling, and bicycling are the most environmentally sustainable forms of transportation and also connect pedestrians to mass transit. As the United Nations New Urban Agenda emphasizes, modern cities need well-designed sidewalks not just for equitability and walkability but to support local commerce and efficient transit.

Connecting sidewalk accessibility to cities’ economic interests, including commerce and sustainability, can show a bottom-line impact of safer sidewalks and prompt walkability/rollability improvements.

Once your project finds obstacles on streets and sidewalks, what steps can be taken to fix them?

In some cities, we have partnered directly with a transit department or municipality charged with urban planning and sidewalk improvements. In others, we work with advocacy or community organizations. Either way, the hope is to improve transparency, government accountability, community involvement, and, ultimately, sidewalk design and navigability with our data.

How do you engage diverse groups in Project Sidewalk?

When a governmental or community organization asks us to deploy in their city, we have a list of considerations, including the presence of a strong local partner, data collection plan, and the potential inclusion of people with disabilities in the collection or analysis of the data.

What do you aim by making your data and source code open for other people and organizations?

We strongly believe in open data and transparency to affect change and support people’s efforts to analyze and visualize our sidewalk datasets. For example, one user created a visualization of our Washington, D.C. data, which received local press coverage. Another integrated our Mexico data into an urban planning tool. These activities were only possible because of open data. Moreover, our codebase is also open source, and we have had contributions from over 50 developers.

With COVID-19, open spaces have become even more important in cities. Does Project Sidewalk have any plans to help make parks and shared open spaces more accessible?

This is a really important point. We have discussed ways of evaluating park accessibility at a large scale by modifying of our methods, but we have not yet made progress. We plan to work on this issue more as we go forward.

Related links:

- Subscribe to our Sustainable Cities newsletter

- Follow @WBG_Cities on Twitter

Join the Conversation