Flooding in Indonesia

Flooding in Indonesia

Discounts, whether a percentage off, a buy-one-get-one-free deal, or an online coupon code, are a great way for people to pay less for what they want, and stretch their budgets. Governments, too, want to make the most of their money, especially for unexpected events such as disasters which are costly and the full amount must be paid.

The 21st century has seen an evolution in the way we manage disaster risk and how governments are paying the disaster bill. We know that disasters hinder development, and that when disasters strike, the poor and vulnerable are often the most affected and fall deeper into poverty. So in addition to responding to disasters, governments have prioritized preparing for future disasters by understanding the causes of disasters, managing underlying risks, and leveraging advances in technology and data availability to look more systematically at hazards, vulnerabilities, and risks.

Understanding the drivers of risk can lead to more efficient use of public resources, and risk information can help us better anticipate, prepare, and respond. Finance ministries around the world are attempting to identify the extent of government responsibilities for natural hazards, also known as contingent liabilities, and several countries have developed ex-ante disaster risk financing strategies (DRFS) to anticipate financial needs when disasters strike.

In most cases, a layered approach to DRFS has been developed (Figure 1) using different financial instruments to bridge financial gaps identified according to the country’s risk profile. This has also allowed the development of risk transfer and risk retention instruments. For example, national emergency funds have been made to collect and disburse money more efficiently; insurance schemes have been developed to promote private and public adoption; contingent lines of credit with multilateral development banks have been created; and parametric insurance, reinsurance, and catastrophe bonds for larger layers have been made available.

A layered approach not only allows the development of strategies and financial tools ex-ante, but also the protection of the governments’ budget through a better understanding of future financial needs related to potential disasters. Not too long ago, most of the budgets used for rehabilitation and reconstruction following a disaster consisted of the reallocation of the national budget, or simply the accumulation of funds leftover from previous reconstruction plans which were not implemented.

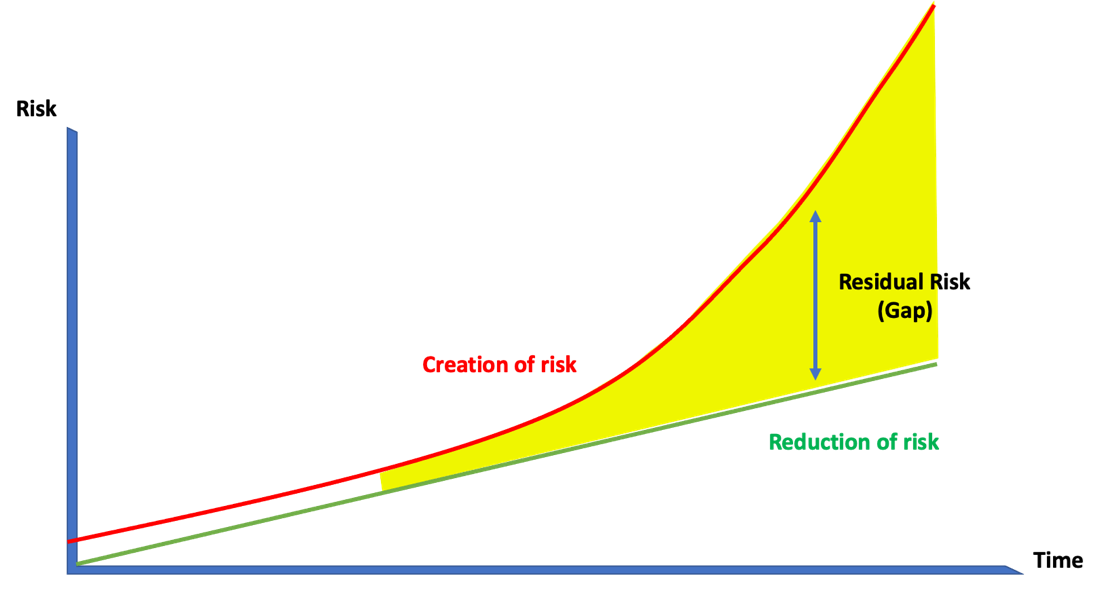

Despite the progress, most of the methods to estimate contingent liabilities for the development of DRFS are based on a static picture of current risk, ignoring that risk is dynamic, heavily accelerated by climate change, and increasing faster than we are reducing it. In short, while risk reduction efforts increase in a linear manner over time, risk is growing exponentially (Figure 2). Lack of building codes, inexistent or bad territorial planning leading to informal settlements, uncontrolled urban expansion, and inequality in access to services all lead to increased vulnerabilities and feed risk. This leaves us with a growing gap, a bill that governments can’t pay.

A solution to address risk growing exponentially is to embed prevention (prospective) and risk reduction (corrective) activities as the first layer of DRFS (Figure 3). This way, we are not only systematically reducing the existing residual risk, but also laying the ground for reducing the longer-term gap between creation and reduction of risk.

To develop a prospective and corrective risk management layer, we must first identify which sectors and areas are the ones that contribute the most to the bill governments will have to pay if a disaster occurs. This will feed into the prioritization of prevention (prospective/future) and risk reduction investments within the finance ministry, in conjunction with sectoral ministries, agencies, and subnational governments which are oftentimes responsible for the creation of these contingent liabilities.

If risk reduction is the first layer of DRFS, governments can reduce the cost of risk transfer instruments and prioritize risk reduction investments. Enforcing building codes, for example, can reduce liability and the cost of insurance or catastrophe bonds in the event of an earthquake. Similarly, if no construction is permitted in high-risk areas, there will be no risk and no liability, which will not exist or grow over time. Retrofitting critical infrastructure can also lower insurance costs while ensuring the continuity of essential services, governance, and businesses in the absence of insurance.

We will always be rushing to catch up with growing disaster risks. But if we include systematic risk reduction/adaptation to climate change as an explicit layer of managing contingent liabilities from disasters, this can be considered as a “discount code” for governments. With fewer bills to pay, governments can make more efficient use of resources to protect and grow development gains.

For more information on disaster risk financing, please see Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery’s (GFDRR) website.

Join the Conversation