It was 1980 and the architect, Barjor Mehta, was deeply disappointed. There were no houses, no people and no chance that they would ever come, given the seemingly god-forsaken location—in an area called Arrumbakkam—so far from the city center in Madras (now Chennai). Having just completed his thesis on housing, he wrote a scathing news article in the Times of India denouncing the sites and services approach. Barjor wasn’t alone in his critique, and by the mid-1990s the World Bank had almost entirely abandoned such projects.

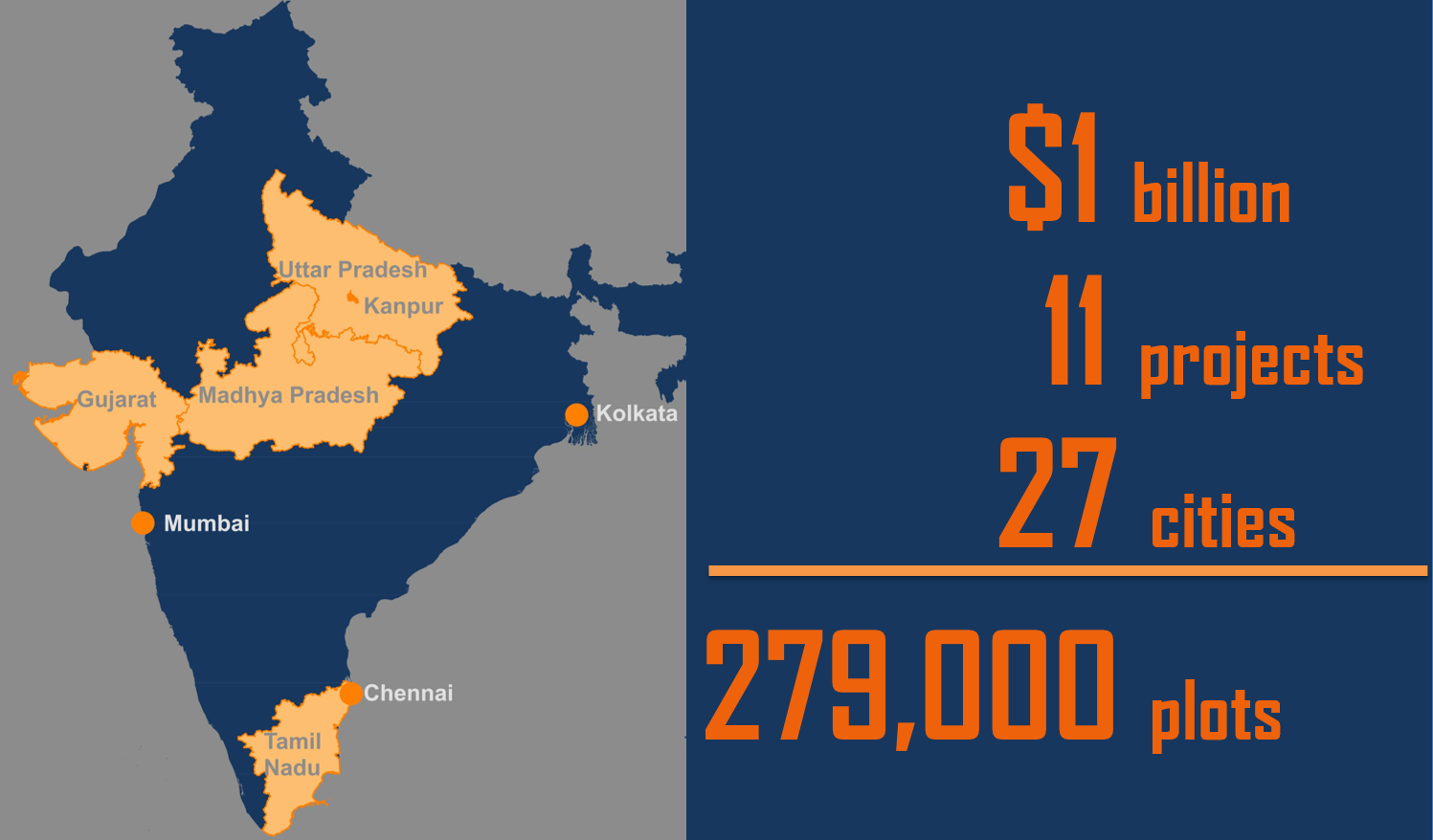

In October 2015, Barjor, now Lead Urban Specialist at the Bank, invited me to revisit Arumbakkam and other neighborhoods developed, between 1977 and 1997, under four Bank-supported sites and services projects:

- Madras Urban Development Project

- Second Madras Urban Development Project

- Bombay Urban Development Project

- Tamil Nadu Urban Development Project

Why?

Twenty years after completing our last sites and services projects, we found bustling and thriving neighborhoods in all but one of the 15 sites we visited. The neighborhoods are almost fully built out and built up—not only did people come, but they also invested heavily. There are houses on almost all plots; less than 10% of plots are vacant. People have invested to add space, upgrade amenities, and improve construction materials, quality, and appearance. Although there are still a few small single-room and single-story units, most of the houses are 2-3 levels. Families have added bathrooms and kitchens on each floor. They have replaced tin roofs with tiles or concrete, strengthened foundations and the superstructure, and upgraded walls and facades. The idea of “incremental” housing—where people would invest slowly, over time, at a pace that fitted each individual family’s circumstances—has worked.

- A key innovation was the introduction of plots that were tiny compared to those “standard” at the time. The smallest plot was 33m2 in Chennai and 21m2 in Mumbai, as compared to minimum plots of about 150-200 m2 in other housing developments in these cities. The small plots were far more affordable and have indeed allowed lower-income households to enter the housing market.

- Another innovation was to use spatially-efficient site planning norms that helped lower the unit costs of developed plots while further increasing density. For example, only 34% of land was allocated to streets and open spaces, compared to 50-60% frequently seen in other developments in India at the time. Even so, average road density in these neighborhoods is actually higher than that in their parent city as a whole. Smart planning, thus, lowered the cost of infrastructure provision and individual housing plots, while creating compact, walkable and livable neighborhoods.

- A key design feature was inclusion of a range of plot sizes that would attract different income groups. In Chennai the plot sizes ranged from 33m2 to 223 m2, and in Mumbai from 21m2 to 100 m2. Now, the neighborhoods are indeed mixed-income, with lower-income families occupying smaller plots, and middle-income and high-income families occupying larger plots.

- Finally, the design explicitly aimed for mixed use by including commercial areas (shops), amenities (schools, clinics), and, in some cases, plots for light industry. As per plan, the current neighborhoods actually do have all of these types of businesses, services, and amenities. Mixed-use has also translated into vibrant streets.

In Mumbai, the sites and services neighborhood of Charkop (left) is characterized by a dense, well-planned, and spatially-economical layout. The private development on a neighboring parcel (right) has fewer roads, larger buildings, and planning that is less efficient.

Second, both governments and private firms can create more affordable housing by scaling up delivery of small housing plots where families can build incrementally. This represents a housing solution that, in terms of cost, lies in between the two classic options—in-situ slum upgrading and public housing—but, potentially, offers quality and livability that is superior to both.

In Chennai and Mumbai many of the families residing in sites and services neighborhoods feel they hit the housing jackpot. Governments should strive to make this option available to many more, not just a lucky few. And in the process, they can build new neighborhoods and cities that are more compact, more inclusive, more vibrant, and more livable.

We see this work as the start of an important conversation and a call for more in-depth research. Do you know of cases that confirm or challenge the findings above? Please share your comments with us.

(Update March 2017) Following the publication of this blog post, we prepared a paper elaborating on these findings. We invite you to download the draft paper and provide your feedback or comments below.

(Update March 2018) Now you can read the peer-reviewed paper! Download it here for free until April 22, 2018.

Join the Conversation