Part of the World Bank’s new vision is to step up its efforts to help fragile and conflict-afflicted states break the vicious cycle of poverty. But this is no easy task.

Part of the World Bank’s new vision is to step up its efforts to help fragile and conflict-afflicted states break the vicious cycle of poverty. But this is no easy task.

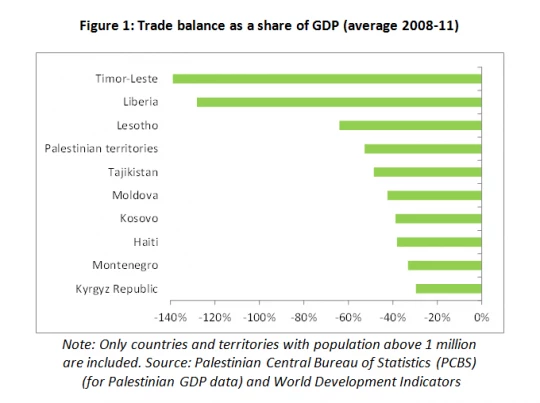

The destruction of productive assets and the restrictions on the capacity to produce are among the most severe economic impacts of conflicts and fragility. These effects explain why countries in conflict or emerging out of conflict typically have very large trade deficits. The productive sector is often particularly weak by international standards, so exports are low and domestic consumption has to rely on imports. Indeed, five of the ten countries with the largest trade deficit in the world (Timor-Leste, Liberia, the Palestinian territories, Kosovo and Haiti) are considered fragile by the World Bank and other regional development banks (figure 1).

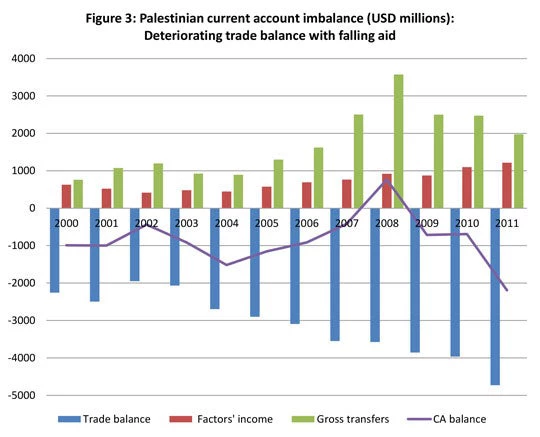

But the bottom line is that without foreign aid many fragile countries would not be able to fund much of their basic consumption and investments. Take the world’s ten most aid-dependent countries with a population above 1 million (figure 2). The top seven are all considered fragile. All five also have a trade deficit well in excess of 20 percent of GDP, with Afghanistan being the only exception (with a deficit of 18 percent of GDP).

A vivid —albeit unique— illustration of this ‘fragile country’ tale is provided by the Palestinian territories. Here, we see both one the highest trade deficits and aid dependencies in the world.

Our recent World Bank report helps explain why. It examines the economic impact of restrictions on movement and access imposed by Israel on Palestinian activities in “Area C”—a contiguous territory spanning 61 percent of the West Bank. Under the Oslo Peace Accords in 1993 this was defined as the area that would be gradually and almost entirely transferred to the Palestinian Authority within a period of 5 years. This transfer is yet to take place.

In the meantime, access to Area C has been drastically limited due to Israeli security concerns. This has meant little possibility for most kinds of Palestinian economic activity, as the de facto manner in which the area is currently administered precludes Palestinian businesses from investing there.

Yet, the potential contribution of Area C to the Palestinian economy is large. Area C contains the majority of Palestinian natural resources. Our estimates suggest that the potential value added from lifting the restrictions on access to, and activity and production in Area C amounts to some USD $3.4 billion —or 35 percent of Palestinian GDP (based on 2011 figures).

The bulk of this potential would come from the tradable sectors, particularly agriculture and minerals-based industries. The restrictions have stifled agricultural production by limiting access to fertile land and the water to irrigate it. Cultivating the additional unexploited area notionally available to the Palestinians could mean adding up to at least US$704 million to the Palestinian economy—equivalent to 7 percent of total GDP in 2011.

The report also estimates that the Palestinian economy could generate more than USD $900 million in additional value added if it were allowed to mine valuable Dead Sea minerals. That’s roughly the equivalent of the contribution of its entire manufacturing sector. Moreover the restrictions are harmful for other important exporting sectors as well, such as mining, quarrying and tourism.

Taken together these restrictions play a major role in explaining the long-term decline of the Palestinian tradable sector. The manufacturing sector has shrunk in real terms since 1994, with its share in GDP falling from 19 to 10 percent by 2011. The importance of the agricultural sector in the Palestinian economy has also diminished. However unlike in a modernizing economy, this process has not been accompanied by any corresponding movement of workers out of agriculture into more productive sectors. Nor have these sectors been replaced by high value-added service exports like IT or tourism.

So how can it be that the numbers still showed until recently the Palestinian economy being in balance?

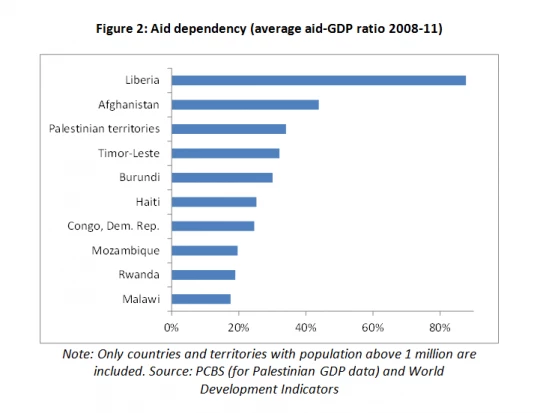

As in the tale of many other fragile and conflict-affected countries, the trade deficit generated by a weak tradable sector has been compensated by external resources. In the Palestinian territories, these have been aid inflows (essentially gross transfers in figure 3).

The aid inflows almost single-handedly maintained the Palestinian current account in balance up to 2010. By 2012, however, foreign budget support—a key component of aid inflows to the Palestinian territories — had declined by more than half. As a result, GDP growth fell from 9 percent in 2008-11, to 5.9 percent by 2012, and to 1.9 percent in the first half of 2013. In the West Bank growth has actually completely stopped, with the economy shrinking 0.1 percent.

This slowdown has exposed the distorted nature of the economy and its artificial reliance on donor-financed consumption. It provides resounding confirmation that any efforts to ensure fragile countries’ sustained economic development—falling short of ending instability and its associated disruptions—is to prove elusive.

Join the Conversation