In February, the United Nations named 2013 the Year of Quinoa and made the president of Bolivia and the first lady of Peru special ambassadors to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The World Bank joined in with a kick-off event and celebration of Bank-funded work that is helping Bolivian quinoa farmers bring their product to market. The focus on this nutritious “super-food,” which is grown mainly in the Andean highlands, is an effort to decrease hunger and malnutrition around the world.

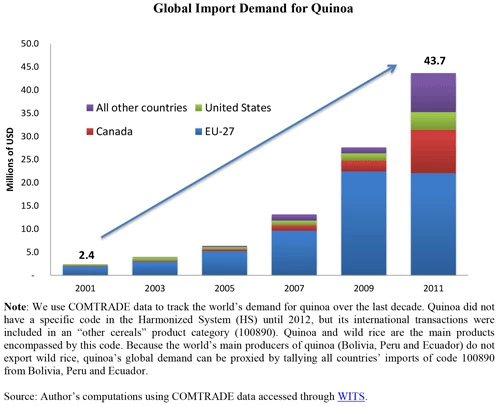

Quinoa (pronounced KEEN-wa) has long had good-for-you credentials. In 1993, a NASA technical report named it a great food to take into space. (“While no single food can supply all the essential life sustaining nutrients, quinoa comes as close as any other in the plant or animal kingdom.”) The pseudo-grain –which is more closely related to beets and spinach than to wheat or corn – has been promoted in recipes distributed by the National Institutes of Health, the Mayo Clinic and the American Institute for Cancer Research. In fact, quinoa already has done quite well on the world stage. Global import demand has increased 18-fold in the last decade, mainly due to consumption in Europe, Canada, and the U.S.

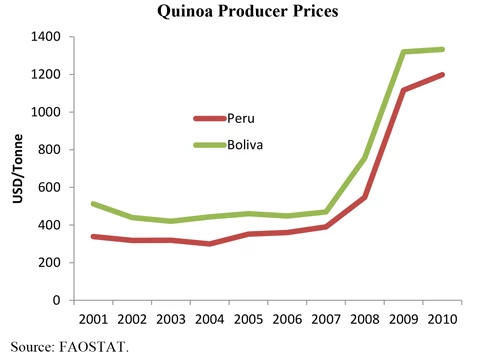

Here, using data from the FAO and individual countries, we show how global production has responded to this increase in global import demand and how international prices have adjusted. We hope to shed some light on important questions: Who produces this wonder-food? What does this sudden, global popularity mean for quinoa’s farmers? What does it mean for the product’s traditional consumers in South America? And finally, what is next for quinoa?

World production of quinoa has grown from approximately 46,000 to 80,000 metric tonnes in the last ten years. According to FAO data, this production is almost evenly split between Bolivia and Peru. Peru, however, has a higher product yield; its harvested area in 2011 was around 60% of that in Bolivia.

Booming demand for a healthy food is generally good news. Higher global demand for quinoa means higher prices for quinoa farmers. This provides farmers with more income, which in turn helps bolster the local labor market and generally boosts local spending. Peru, for example, has looked to agricultural trade as a source of export diversification and economic growth. It has succeeded in expanding its exports by promoting niche agricultural products such as asparagus, and has now turned its attention to quinoa.

But those higher prices that help farmers can also adversely affect local consumers. This is a downside of the quinoa boom. It can mean that poor people in Bolivia and Peru have less access to quinoa, a traditional and healthy component of their diet. The higher price might force them to shift consumption to other types of food, as has been reported in Bolivia.

Assessing the true impact of rising food prices is a very complex exercise, however, and some would argue that a shift away from ancient grains such as quinoa is inevitable as Andean societies become more affluent and have better access to a more diverse range of imported foods. In addition, it is difficult to determine whether rising quinoa prices help farmers more or less than they hurt consumers. Some would argue that many of the poorest families in Andean countries are, in fact, farmers who benefit from higher prices. The poorest families also may be consumers who eat daily staples such as potatoes and fava beans far more than quinoa. Without a comprehensive study, it is difficult to determine the distributional effects of higher prices on domestic welfare.

The future of quinoa prices is uncertain, but already new countries are experimenting with quinoa production, including Canada, China, Denmark, Italy, India, Kenya, Morocco and the Netherlands. Last year, the United States Department of Agriculture awarded US researchers a $1.6 million grant to study the basics of growing quinoa, including its heat tolerance and response to high-salinity soils and dry conditions.

According to the UN, quinoa has proven to be a hearty crop, thriving at temperatures ranging from -8 degrees Celsius to 38 degrees Celsius. It can grow at sea level or 4,000 meters above and is not impacted by droughts or poor soils. Some have suggested that quinoa could help mitigate food shortages in some of the poorest countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, which are subject to harsh growing conditions.

This, of course, would be a wonderful outcome. But it is important to remember that Bolivian and Peruvian farmers now profiting from quinoa thriving demand might be affected by competition. New producers with access to advanced technologies, such as the Netherlands and the US, may eventually be able to grow the crop more efficiently and with economies of scale. For this reason, Bolivia should take advantage of the boom now, but be careful not to become too dependent on quinoa production as a source of exports and growth. Even a "super food" can have a change of fortune.

Join the Conversation