Sunny skies and beautiful beaches come to mind when you think about the Caribbean. But beyond the turquoise water lies a history of underage marriage, a practice that still lingers throughout the region.

My Nani (the Hindi word for maternal grandmother), came from a low-income family from the island of Trinidad. Growing up, she worked on a sugar plantation with her siblings. But poverty and manual labor didn’t compare with what she experienced after her mother died.

My great-grandmother’s early death left her husband with six children to care for. Driven by economic pressure, he married them off one by one. My Great-Aunt was married at 12. And my Nani was 16 when she found herself wed in a traditional Hindu ceremony. She lost her chance to get an education and entered a hard new life.

During the first five years of marriage, she had five miscarriages, suffering physically and psychologically. She finally had my mom, and then gave birth to another four children in a short span of time.

Child brides are more susceptible to abuse, and my Nani was no exception. My grandfather’s treatment of her created an unstable environment in their family. She persevered and decided not to continue the tradition of child marriage with her children

But child marriage still persists throughout the Caribbean. The Dominican Republic has the highest rate in the region, with close to 37% of all marriages there occurring by age 18. In Trinidad and Tobago, where I come from, at least 747 girls became child brides between 2005 and 2009. This may sound small, but on an island of only 1.3 million people, it is quite significant.

How can countries like Trinidad and Tobago tackle child marriage?

While Trinidad and Tobago sets the legal age of marriage for girls and boys at 18, legislation allows girls to marry at any age with their parent’s consent. And child marriage is neither legally prohibited nor penalized.

The World Bank Group’s Women, Business and the Law project tracks laws on child marriage. In its 2016 report, it found that only 19 of the 173 economies examined have set the legal age of marriage at 18 or older without exceptions. Closing the Gap—Improving Laws Protecting Women from Violence, a brief note just released, found that female enrollment in secondary education is higher where the legal age of marriage for girls is 18 years or older.

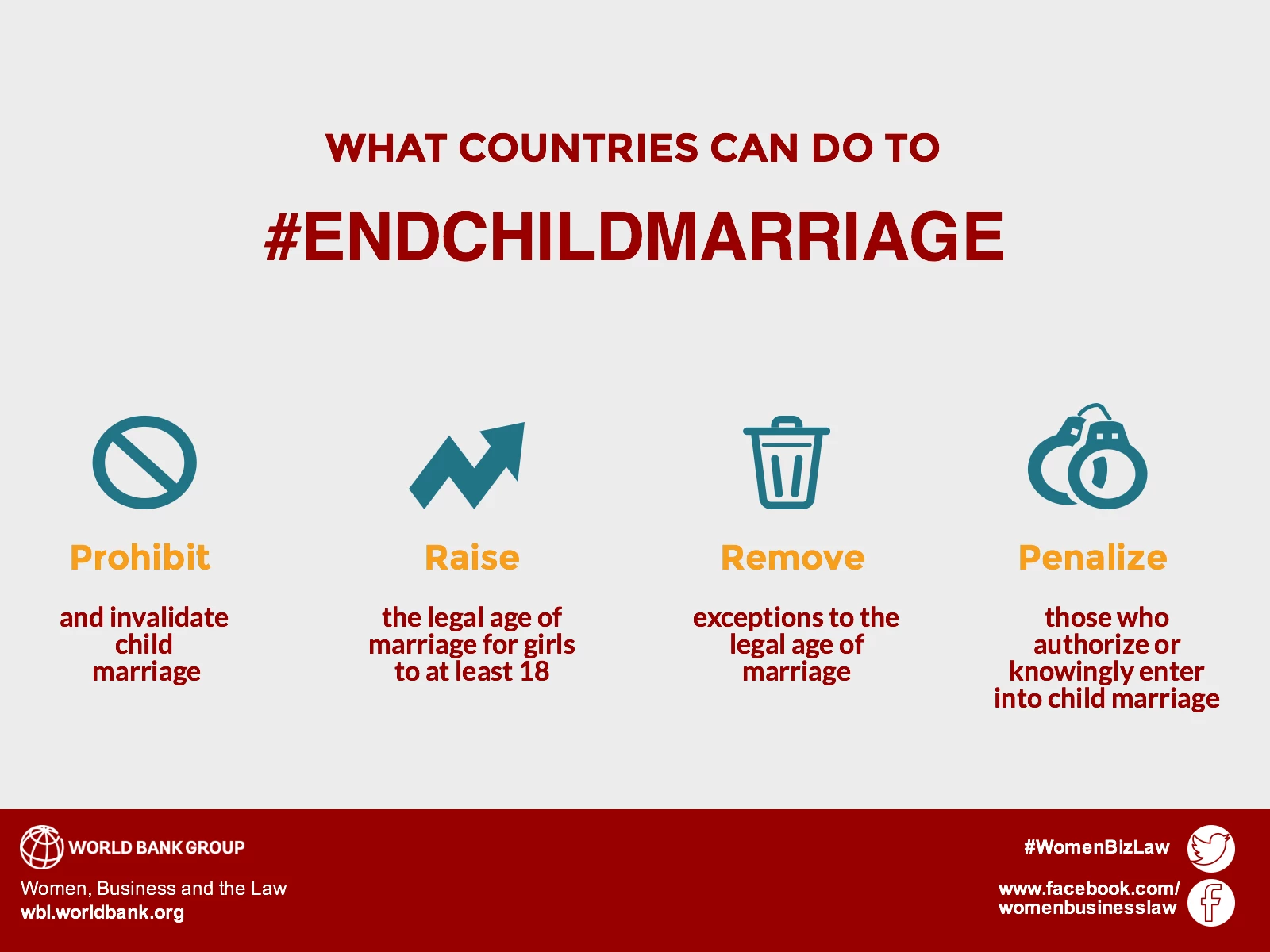

Countries can do more to stop child marriage by establishing better legal protections and removing exceptions to the legal age of marriage—which every country in the Caribbean still allows. Some countries in the region have made progress, however, for example: the Bahamas, Belize, Haiti, and Jamaica have both legally prohibited child marriage and established penalties.

And several countries outside the region have also recently made head-way. Women, Business and the Law found that between 2013 and 2015, five countries—Egypt, India, Kenya, Sweden and Vietnam—set the legal age of marriage at 18 for girls, removed all exceptions, prohibited child marriage and established penalties.

Ending the cycle of child marriage allowed my mother and her siblings to break out of poverty. Empowered and educated, my mother and her sister provided better futures for their own children. With better legal protections from child marriage, women like my Nani can also break the cycle of poverty.

Join the Conversation