The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development rightfully points out that sustainability has three dimensions: economic, environmental, and social. The first two are well understood and well measured.

Economic sustainability has a whole strand of literature and the World Bank and IMF devote a lot of attention to debt and fiscal sustainability in their reports. Just open any Article 4 consultation or any public expenditure review and you will find some form of fiscal or debt sustainability analysis.

The same can be said about environmental sustainability. Since Cancun (COP16), countries prepare National Adaptation Plans, and since COP 21, they have prepared Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) which focus on domestic mitigation measures to address climate change.

Yet, despite the 2030 Agenda’s inclusion of this dimension of sustainability, there is nothing, however, to measure, report, or evaluate social capital. In addition, if you evaluate the 169 SDG targets or the 230 or so indicators through which we are to monitor the SDGs, surprisingly few are focused on social sustainability.

Clearly social capital is an important contributor to development. In our opinion it is time to revive the measurement of social capital. Definitions vary but generally boil down to those networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, who show trust in and solidarity with one another, all while enabling that society to cooperate and function effectively.

Luckily we do not have to start from scratch. In the past, the World Bank and others have sought to measure social capital and its impact and importance for successful development. It is time to revive those efforts and invest in measuring social capital. We should learn from the past, start modestly and build on efforts that are ongoing instead of trying to build a Ferrari as was done in the early 2000.

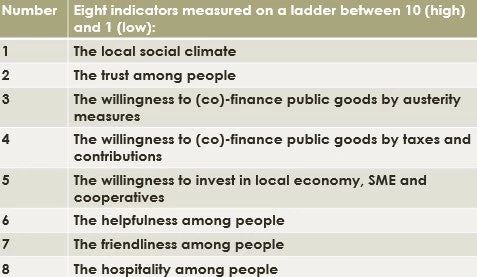

The most recent attempt to measuring Social Capital within the UN SDGs Partnerships is the World Social Capital Monitor (see table 1), that allows stakeholders to score eight characteristics of social capital. The template allows this to be done online or on any mobile device, in 37 languages and in 141 countries. We invite you to participate and it takes only a few minutes. The more people who participate, the more relevant its outcomes.

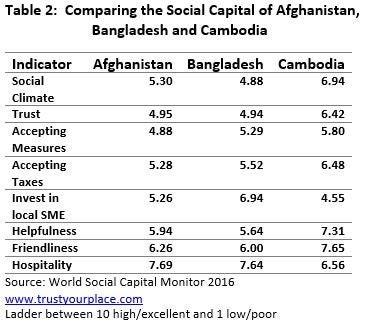

The survey already shows some surprising results: the willingness to co-finance public goods in countries such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Cambodia (see table 2) is basically at the same level as in many industrialized countries. Meanwhile, hospitality and friendliness -- core assets to achieving peace and reconciliation -- reach a top level in regions of conflict such as in Afghanistan, Palestine, and Pakistan.

The full inclusion of these social capital measurements is necessary to meet the standards set in the 2030 Agenda. It is also a critical step toward helping countries reach their goals to end extreme poverty, fight hunger, promote health and employment, and meet all the ambitious objectives embedded in the Sustainable Development Goals.

Alexander Dill is founder and CEO of Basel Institute of Commons and Economics.

Jos Verbeek is manager and Special Representative to the WTO and UN in Geneva.

Join the Conversation