When COVID-19 hit, Indigenous peoples feared for the lives of their elders and the survival of their cultures. Despite lockdowns, there seemed to be a surge in territorial invasions, contributing to the ensuing spread of the virus in their remote communities. Many were without water, sanitation and days away from the closest health clinics. Indigenous leaders called for help to mobilize food, water, soap, PPE, thermometers, and tests. Surprisingly, some of the most desperate stories were coming from Indigenous communities that, prior to the pandemic, had in many cases fared better economically, given their links with tourism, external markets, and informal urban employment. Relief efforts were also difficult. The rollout of emergency response programs often indirectly excluded Indigenous Peoples through eligibility requirements, such as electricity bills, and delivery mechanisms, such as urban grocery stores.

In the midst of this crisis, Indigenous Peoples turned inwards to find resilience. As stories of COVID spreading through their communities began to reach global headlines, so too emerged accounts of Indigenous-led health brigades. These brigades, alongside traditional healers, became among the primary and in many cases the only source of relief for many Indigenous communities. As one quote read: “More than vulnerability, we Indigenous peoples have demonstrated resilience over centuries of pandemics, and this will not be the last time.” This message would become a reality in the images of Amazonian Indigenous women with banana leaf face masks and in the mobilization of Indigenous leaders to collect and deliver fresh food to their more vulnerable brothers and sisters.

So, what made some Indigenous peoples resilient and others not? Why was it that some Indigenous peoples, who were better off pre-pandemic, were among the most desperate, while others were able to self-organize, avoid infection, maintain food security, and help others?

Natural Capital

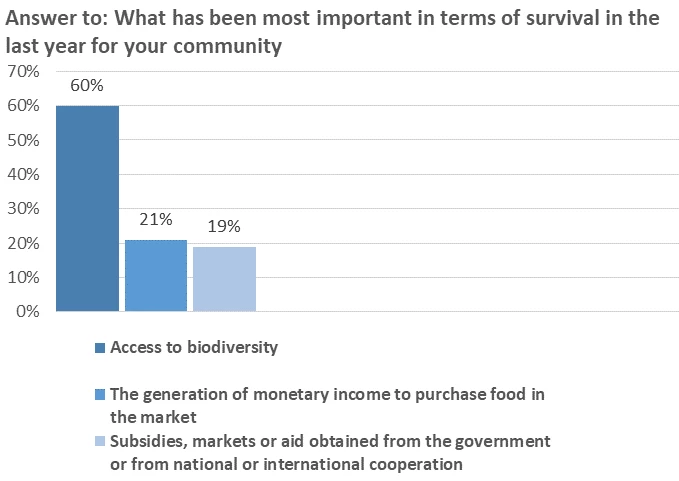

During the pandemic, it was those Indigenous Peoples with secure rights and access to lands and natural resources that were able to produce food, gather plants and herbs for medicine, and isolate to avoid contagion. The Central American surveys found that 60 percent of respondents deemed that access to biodiversity was the most important resource for their community’s survival during the pandemic, far above income or subsidies from governments or international cooperation.

Cultural Capital

Traditional knowledge, medicine, and non-monetary economies have been critical for Indigenous peoples to leverage their natural capital for survival. Traditional medicine has been the primary, and in many cases, the only health resource for Indigenous peoples during the pandemic. The Central American surveys found that traditional healers far outnumber western health specialists working within Indigenous communities. Within the communities surveyed, 97% of respondents reported relying on traditional medicine to treat their health needs during the pandemic, and of these, 80% reported midwives as the primary care source for pregnant women.

Traditional Indigenous economies were vital for food security. These economies rely on a collective organization of production and care for the most vulnerable through the exchanges of food, seeds, medicine among families and communities. Among the 15 communities surveyed, seven had highly active traditional economies with 70 percent or more of their food attained through self-production or inter-communal trade. Of these, five reported no food shortages or hunger over the past year. To the contrary, the three communities who reported the most severe food shortages and hunger had a much higher dependence on purchasing food from external sources. For example, an Embera community in Chargre, near Panama City, who was dedicated entirely to tourism and enjoyed a relatively low poverty rate (23 percent) pre-pandemic, found themselves without food or income once the pandemic hit. Their survival depended greatly on the solidarity of others, including that of the much poorer Embera communities (48-70 percent), living within their ancestral territories, who sent food for over three months.

Social Capital

Social cohesion and solidarity are at the foundation of Indigenous cultures throughout the world. Communities with strong traditional governance structures were able to close community borders, organize support for the most vulnerable within their communities, broadly distribute seeds, activate traditional economies for food production, and coordinate efforts with government authorities. The Central American surveys found that in 12 of 15 communities women managed the family income and led efforts to mobilize limited family savings and community bank resources for the most vulnerable.

Over the last year, the World Bank has put forward different frameworks committing the institution to principles around inclusion and sustainability, including through the COVID-19 Response and Recovery, Building back through a Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development Model (GRID) and a Climate Change Action Plan (2021-2025). These frameworks create a platform for the Bank to support Indigenous Peoples’ resilience. Experience witnessed globally and lessons from the Bank’s ongoing dialogues with Indigenous Peoples indicate that supporting their resilience will require nuanced approaches that recognize, safeguard, and empower their own capital—which is highly intertwined with their secure access to lands and natural resources and their traditional knowledge, medicine, and economies.

Join the Conversation