Photo credit: Shutterstock

Photo credit: Shutterstock

This blog is a repost from the Brookings Institute, first published on March 18, 2022.

Inflation has returned, and it is wreaking havoc. Surging economic activity, supply-chain disruptions, and soaring commodity prices combined in 2021 to push global inflation to its highest level since 2008 (Figure 1). Among emerging market and developing economies, inflation reached its highest level since 2011. It now exceeds inflation targets in more than half of these economies with an inflation-targeting framework.

With the war in Ukraine, matters are going quickly from bad to horrid. Food and fuel prices have spiked, as Russia and Ukraine are big exporters of many commodities including gas, oil, coal, fertilizers, wheat, corn, and seed oil. Several economies in Europe and Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa are almost entirely dependent on Russia and Ukraine for wheat imports. For lower-income countries, disruption to supplies as well as higher prices could cause increased hunger and food insecurity. And disruption to supply chains could broadly intensify inflation pressures.

For many households across the world, rising inflation poses a significant challenge. Higher prices can erode the value of real wages and savings, leaving households poorer. But these effects are not felt equally: Low- and middle-income households tend to be more vulnerable to high inflation than wealthier households. That reflects the composition of their income, assets, and consumption baskets. Inflation may affect the very poorest households living below the global poverty line less directly, however. That’s because the poorest households have minimal wage incomes or assets and tend to rely on nonmonetary income, such as subsistence farming or barter, which may be less vulnerable to inflation.

COMPOSITION OF INCOME

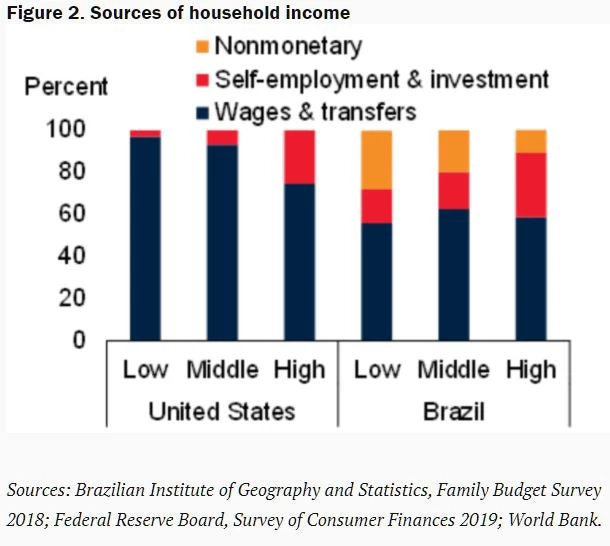

In advanced economies, low- and middle-income households tend to rely more heavily on wage income and transfer payments than wealthier households (Figure 2). Price inflation often outstrips growth in wages and transfers, while self-employment income and investment income may be more likely to keep pace with inflation. As such, inflation can reduce the incomes of poorer households relative to those of the richest. Among emerging market and developing economies, the picture is similar. In Brazil, for example, self-employment and investment income account for a larger share of income in high-income households than in low- and middle-income households. However, the very poorest households also rely on nonmonetary income.

COMPOSITION OF FINANCIAL ASSETS

Poorer households often lack access to financial products that can protect them against inflation, because these products can have upfront or ongoing costs and therefore be unaffordable. In the United States, for example, almost all households have a transaction or checking account at a financial institution. However, far fewer households have savings or investment products. The distribution, moreover, is highly skewed: The wealthiest quartile of U.S. households is five times as likely as the poorest to hold certificates of deposit, six times as likely to hold savings bonds, and 12 times more likely to hold investment funds.

High inflation, in short, tends to worsen inequality or poverty because it hits income and savings harder for poorer or middle-income households than for wealthy households. Households that have recently escaped poverty could be pushed back into it by rising inflation.

COMPOSITION OF CONSUMPTION BASKETS

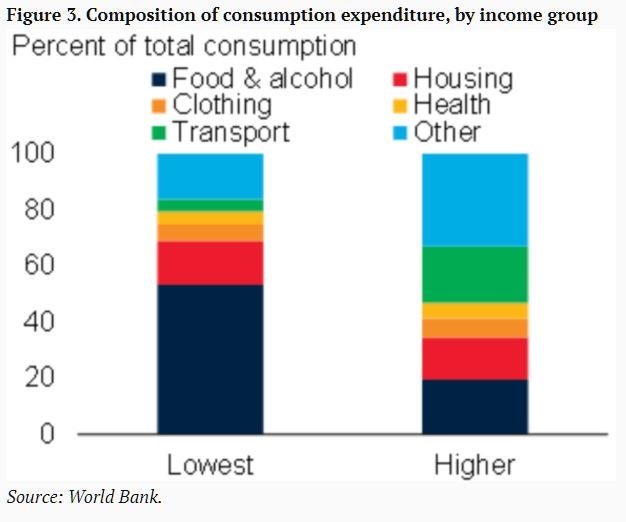

Poorer households may actually experience higher rates of inflation than wealthy households. Consumer-price inflation measures are calculated using a basket of goods that is representative of the average consumer. But the actual composition of spending varies significantly by income group. For example, the lowest-income households in emerging and developing economies spend roughly 50 percent of their income on food. For the highest-income households, the amount is just 20 percent (Figure 3). The recent increase in food and energy prices could disproportionately impact the poorest households. High-income households can easily switch from higher-quality goods to lower-quality goods in times of economic crisis. They can also take greater advantage of discounts on bulk purchases and sales. Poor households ordinarily don’t have those options.

In some emerging and developing economies, rising food prices do hold the potential to benefit a sizeable segment of the poor. In the average developing economy, more than one-fifth of households around or below the poverty line are net food sellers, so higher food prices could be good for them. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the poor in developing economies remain net buyers of food, so food-price spikes tend to increase poverty overall.

WHAT POLICYMAKERS CAN DO

Governments have been turning to subsidies to dampen the impact on households. In some cases, subsidies can be an effective transitional tool to ameliorate the impact of shocks. But they tend to be left in place for too long, leading invariably to adverse effects. Subsidies can quickly detract from spending in infrastructure, health, and education. Energy subsidies tend to go to wealthier households more than poorer households and encourage excess consumption.

Worryingly, many governments are considering the use of trade restrictions and export bans to protect domestic supplies of food. They should desist. Policies such as these that seem appropriate at the country level tend to have terrible global consequences. During the 2010-11 food price spike, trade restrictions amplified the increase in world prices and pushed millions of people into poverty, though they dampened domestic price increases.

Policymakers should instead use social welfare policies to protect the poorest from rising prices. These policies could include targeted safety nets such as cash transfers, food, and in-kind transfers, school feeding programs, and public works programs. Calculating inflation indexes for different income groups provides better information on inflation actually experienced by the poor and should inform the design of social safety nets. International cooperation and communication will be needed to avoid tit-for-tat measures.

Central banks in emerging markets and developing economies have also moved swiftly to curb inflation. In deciding what to do next, they should keep in mind the potential effects on poverty and inequality. Governments can also improve their access to financial products that might protect the real value of the assets of poor families against inflation—spurring greater competition in the financial sector will help to achieve that outcome.

Join the Conversation