Жизнь студентов колледжа Тайлулулу в столице Тонга Нукуалофе изменится с появлением в Тонга высокоскоростного широкополосного Интернета. Нукуа'лофа, Тонга. Фотография: Том Перри / Всемирный банк

Жизнь студентов колледжа Тайлулулу в столице Тонга Нукуалофе изменится с появлением в Тонга высокоскоростного широкополосного Интернета. Нукуа'лофа, Тонга. Фотография: Том Перри / Всемирный банк

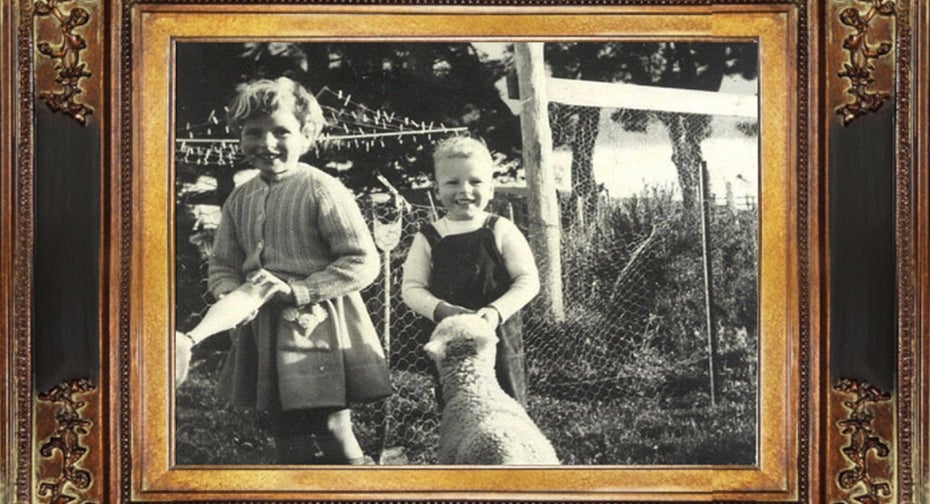

I grew up in Palmerston North in the 1960s during a period of generous government investment in health and education. I was part of a generation that benefited from great child health and early childhood development services, such as free milk given out at school, Playcentre (parent-led early childhood education facilities) and Plunket (an organization that provides support services to parents of newborns). We had opportunities that our parents did not: my Mum and Dad had both left school at the end of what was then Form Two (the sixth year of school), but they were determined that their four children would complete high school.

Today, I am the Vice President for Human Development at the World Bank Group, overseeing financing operations and projects worth more than NZD$15 billion (USD$10 billion) a year—and in no small part this is because I was fortunate enough to grow up in a stable, prosperous country that made effective investments in health, nutrition and education, especially in early childhood.

New Zealand’s success story is often told in terms of its lamb, wool, kiwifruit and agricultural exports. But our country’s greatest asset has always been our people who have been equipped to do amazing things in Aotearoa (New Zealand, using its Māori name) and on the global stage – from Nobel prize-winning scientist Alan MacDiarmid to film-maker Taika Waititi to international dance company Black Grace.

New Zealand’s own development story with its history of investment in ‘building human capital’, to use the World Bank’s language, means our country has much to share with the world and especially low-income countries.

Beyond knowledge-sharing, one of the most effective ways to demonstrate solidarity with the world’s poorest countries is through the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), the fund for the poorest countries, which is negotiating its next three-year funding package with our 55 country donor partners.

New Zealand has been a member of IDA for more than 40 years. In that time, IDA has been hugely successful in helping countries grow their way out of poverty, and many of these successful countries are now themselves donors, and New Zealand’s trading partners.

But the countries that remain poor today are frequently extremely fragile and are struggling to invest in their own people, while also dealing with long-running conflicts and the effects of climate change.

IDA fights extreme poverty by creating opportunities for people in the world’s poorest countries through grants and very concessional loans. It is now the second-largest donor in the Pacific region, supporting 61 projects with nearly NZD$2.35 billion (US$1.5 billion). Since 2011, the number of Pacific operations has more than tripled, while disbursements have more than sextupled.

Many of these grants and loans are delivered in line with the Bank’s global Human Capital Project – an accelerated effort to help countries invest more and more effectively in people. Around the world, nearly 60 percent of children born today will, at best, be only half as productive as they could be if they had complete education and full health and more than half the children living in developing countries cannot read, by the age of ten years.

In Tonga, IDA is helping 10,500 youth to reach their full potential by supporting the government to provide cash transfers so parents can afford to keep their children in high school. We are working too to improve technical and vocational courses to make graduates more employable not only in Tonga but also in Australia and New Zealand.

In Papua New Guinea, support from IDA has helped more than 18,000 disadvantaged young people complete employment training and work placement, and open bank accounts. It has created more than 800,000 days of work, including on projects to improve infrastructure.

As well as supporting human capital, IDA is investing across the Pacific in building systems and infrastructure that can better withstand shocks from climate change, boosting regional integration, helping strengthen debt policies and debt management, and is ready with access to finance when crises occur. IDA’s mission is in lockstep with New Zealand’s Pacific Reset policy in supporting Pacific countries’ resilience to climate change, improved governance, and closing gender gaps.

New Zealand is small but punches above its weight in the international arena. It relies on—but also strengthens—global institutions like the World Bank with its presence and voice. By standing together, we can continue to develop shared prosperity. This is true not only in the Pacific, but also globally. With every $1 we receive from donors, IDA is able to commit $3 to beneficiary countries. This in turn translates into country-led efforts that create improved living standards and greater stability, benefiting everyone. In the Human Capital Project’s first year, 63 low- and middle-income countries have signed up to invest more in their people.

The Gambia, for example, prioritized a program to enable the poorest households to cover basic needs while investing in childhood education. Pakistan launched a flagship policy to use data and technology to reduce inequality. And Mali announced major reforms that will make health services free for under-5s and pregnant women.

I was lucky to be born at a time when New Zealand was able to invest in nurturing Kiwi children. That made my life chances so much greater than those of a girl born today in Chad – a country with one of the world’s highest infant mortality rates. Every single child deserves to be given the head-start that comes from investment in early childhood development, health and education.

By showing solidarity with the world’s poorest nations through IDA, New Zealand can use its experience and voice to export its human development success story —and can continue to use its mana (prestige) to help build greater stability and prosperity around the world.

This op-ed was originally published in The Herald.

Join the Conversation