There’s been a lot of talk about food riots in the wake of the international food price hikes in 2007. Given the deaths and injuries caused by many of these episodes, this attention is fully justified. It is quite likely that we will experience more food riots in the foreseeable future—that is, if the world continues to have high and volatile food prices. We cannot expect food riots to disappear in a world in which unpredictable weather is on the rise; panic trade interventions are a relatively easy option for troubled governments under pressure; and food-related humanitarian disasters continue to occur.

In today’s world, food price shocks have repeatedly led to spontaneous—typically urban—sociopolitical instability. Yet, not all violent episodes are spontaneous: for example, long-term and growing competition over land and water are also known to cause unrest. If we add poverty and rampant disparities, preexisting grievances, and lack of adequate social safety nets, we end up with a mix that closely links food insecurity and conflict. The list of these types of violent episodes is certainly long: you can find examples in countries such as Argentina, Cameroon, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, and Tunisia showcased in May’s Food Price Watch.

How We Can Prevent Food Riots?

There are some serious challenges in trying to answer this question.

First, despite the fact that the term “food riot” is widely used, it is poorly understood. There is no consensus definition: some accounts of food riots involve overly restrictive definitions (for example, including only episodes that have associated deaths); while others are too broad (including even peaceful demonstrations). Not having a consensus or an agreed-upon list of riots only makes it harder to understand which drivers are common to all episodes, and which factors are context-specific.

Furthermore, rigorous empirical analyses have been unable to make a compelling argument that prices of food—and, more generally, of commodities and natural resources—have effects on different types of conflicts. (Again, the May Food Price Watch mentions some of the most relevant literature on food prices and conflict.) In the case of food prices at least, this lack of solid evidence may be explained by the fact that analyses look at the wrong clues, that is, at international prices instead of domestic prices. Looking at domestic prices poses its own problems, chief among them the inability to discern if the results obtained are the consequence of prices on riots or of riots on prices—but ignoring the role of domestic prices in local food riots leaves a huge gap in the current evidence.

So What Can We Do?

We first need to cautiously avoid proposing solutions for a challenge we do not completely understand. An essential first step will be to properly define what a food riot is. In the May issue of Food Price Watch, we propose a new definition that can be commonly used across public policy, media, and academic arenas: a violent, collective unrest leading to a loss of control, bodily harm or damage to property, essentially motivated by a lack of food availability, accessibility or affordability, as reported by the international and local media, and which may include other underlying causes of discontent.

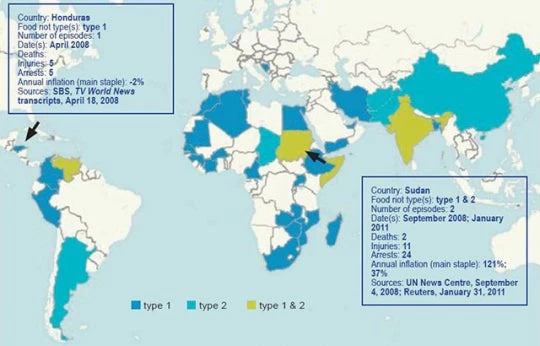

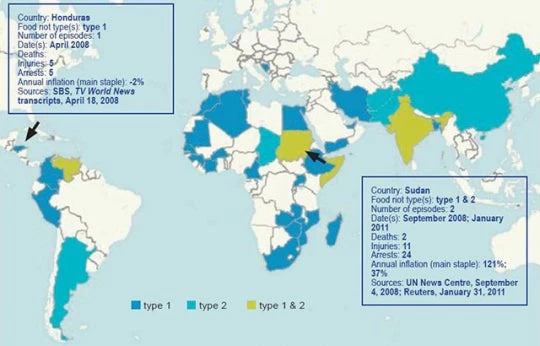

Notwithstanding the difficulties—that is, subjectivities—associated with defining violence and the true degree of responsibility of food vis-à-vis other factors for each single episode, this definition has allowed us to identify and monitor 51 episodes over 37 countries. The following map shows the result of this monitoring exercise for two specific examples, Honduras and Sudan.

We also need to move beyond the simple notion that conflict causes food insecurity (ultimately famines) to one that also incorporates the fact that food insecurity in general, and food price shocks in particular, contribute to instability and conflict. Unfortunately, this is hardly news. As Nobel Laureate and father of the Green Revolution, Norman Borlaug, eloquently put it: “we cannot build world peace on empty stomachs and human misery.” Let’s remember his message as we work toward a more food secure, prosperous, and peaceful world.

In today’s world, food price shocks have repeatedly led to spontaneous—typically urban—sociopolitical instability. Yet, not all violent episodes are spontaneous: for example, long-term and growing competition over land and water are also known to cause unrest. If we add poverty and rampant disparities, preexisting grievances, and lack of adequate social safety nets, we end up with a mix that closely links food insecurity and conflict. The list of these types of violent episodes is certainly long: you can find examples in countries such as Argentina, Cameroon, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, and Tunisia showcased in May’s Food Price Watch.

How We Can Prevent Food Riots?

There are some serious challenges in trying to answer this question.

First, despite the fact that the term “food riot” is widely used, it is poorly understood. There is no consensus definition: some accounts of food riots involve overly restrictive definitions (for example, including only episodes that have associated deaths); while others are too broad (including even peaceful demonstrations). Not having a consensus or an agreed-upon list of riots only makes it harder to understand which drivers are common to all episodes, and which factors are context-specific.

Furthermore, rigorous empirical analyses have been unable to make a compelling argument that prices of food—and, more generally, of commodities and natural resources—have effects on different types of conflicts. (Again, the May Food Price Watch mentions some of the most relevant literature on food prices and conflict.) In the case of food prices at least, this lack of solid evidence may be explained by the fact that analyses look at the wrong clues, that is, at international prices instead of domestic prices. Looking at domestic prices poses its own problems, chief among them the inability to discern if the results obtained are the consequence of prices on riots or of riots on prices—but ignoring the role of domestic prices in local food riots leaves a huge gap in the current evidence.

So What Can We Do?

We first need to cautiously avoid proposing solutions for a challenge we do not completely understand. An essential first step will be to properly define what a food riot is. In the May issue of Food Price Watch, we propose a new definition that can be commonly used across public policy, media, and academic arenas: a violent, collective unrest leading to a loss of control, bodily harm or damage to property, essentially motivated by a lack of food availability, accessibility or affordability, as reported by the international and local media, and which may include other underlying causes of discontent.

Notwithstanding the difficulties—that is, subjectivities—associated with defining violence and the true degree of responsibility of food vis-à-vis other factors for each single episode, this definition has allowed us to identify and monitor 51 episodes over 37 countries. The following map shows the result of this monitoring exercise for two specific examples, Honduras and Sudan.

We also need to move beyond the simple notion that conflict causes food insecurity (ultimately famines) to one that also incorporates the fact that food insecurity in general, and food price shocks in particular, contribute to instability and conflict. Unfortunately, this is hardly news. As Nobel Laureate and father of the Green Revolution, Norman Borlaug, eloquently put it: “we cannot build world peace on empty stomachs and human misery.” Let’s remember his message as we work toward a more food secure, prosperous, and peaceful world.

Join the Conversation