Have you ever seen a rhino walking into the African sunset? It’s an unbelievable sight. Now let me ask you this- have you ever seen a carcass of a dead adult rhino with its horn sawn off and the body lying on the dusty ground? It is an unforgettable and tragic sight.

The world’s wildlife is under a grave threat of either being slaughtered or captured alive. The wildlife commodities -- whether an ivory tusk, a rhino horn, live birds or reptiles -- are illegally moved through well-organized transnational supply chains and sold in international markets where consumers are willing to pay a high price.

Over the years, reports have valued the illegal wildlife trade to be a multibillion dollar industry (UNEP INTERPOL 2016). The opportunity to make huge profits with relatively low risk of punishment has given rise to the involvement of organized crime groups taking advantage of gaps in legislation, and weak law enforcement and criminal justice systems. Using sophisticated schemes they can quickly adapt to changing conditions to keep the supply going. Employing a complex web of poachers, illegal loggers, middlemen, networks of traffickers, transporters, and traders, these criminal groups stay one step ahead of the law. However, the illegal trade is not limited to organized groups as often it is small scale and country based, satisfying local demand or personal needs. The UNODC World Wildlife Crime Report 2016 goes into detail about the extent of the problem and explains how networks operate.

Because of this criminal activity, our ecosystems are being damaged beyond repair and some species of wildlife are being pushed to the brink of extinction. This is contrary to the aim of the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) a binding agreement concerning the trade in wildlife signed by 183 parties to safeguard many species from over-exploitation. Today, it accords varying degrees of protection to approximately 5,600 species of wildlife and 30,000 species of plants from a total ban in trade to trade under controlled conditions.

How do we strengthen law enforcement response to the illegal wildlife trade? Ideally, poaching should be stopped at the site level. This requires effective patrolling by dedicated law enforcement personnel i.e. park rangers with resources and equipment to face well-armed poachers. This is essential for deterrence, interception and in the worst-case scenario having to secure a crime scene. To complement these efforts, park rangers need to work alongside local communities who are the eyes and ears on the ground and can provide valuable information for investigations. The role of communities in law enforcement is essential since there are many small-scale, opportunistic poachers who are easily recognizable. Thus, incentivizing communities and raising local awareness helps law enforcement efforts.

Enforcement agencies need to think like criminals, but act within the law. They need to understand how a criminal group operates and respond quickly to information received. Data is crucial for investigators who seek out crime perpetrators and aim to bringing them to justice under national wildlife laws or the CITES agreement. There are many challenges during this phase since laws are weak, sentences for wildlife crimes are not tough, corruption can lead to the case being dropped, and lack of capacity could lead to the case being overlooked due to technicalities. Furthermore, there needs to be a judicial process that is not hindered by political interference.

Data is also key for intelligence officials who work proactively, building on information to develop intelligence packages on networks and routes. Such intelligence-led operations should lead to disruption, intervention and arrests to prevent crimes from being committed.

To make this all work, it is essential that a robust wildlife crime legal framework exists that allows law enforcement officials to work effectively and efficiently. This requires strong political will and it is the role of government to enact the laws. Additionally, there needs to be careful investment in capacity building, data collection, investigative techniques, intelligence training and judicial training. The Global Wildlife Program, led by the World Bank and funded by the Global Environment Facility is facilitating elements of law enforcement capacity building across 19 countries in Asia and Africa.

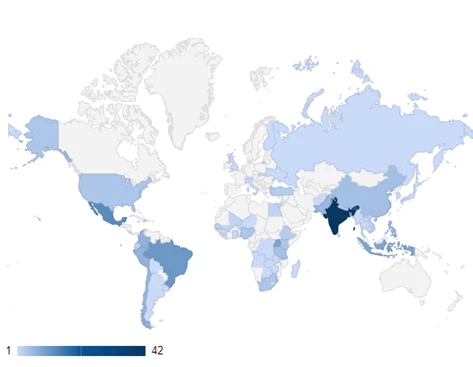

If the wildlife commodity is in transit, intercepting it requires understanding the transit routes (whether through air or ship) and knowing which containers/packages are most likely to contain contraband. The map below represents the flights used to traffic rhino horn products through the air transport sector. This includes instances where the product did not actually enter a country because it was seized earlier in the routes. Each line represents one flight and the bubbles represent the total number of flights to and from each city.

Depending upon the type of commodity, routes change, the mode of transportation changes and the method of concealment differs. For investigators and custom officials who want to intercept and seize the contraband, there are tools and databases that are available to assist in this process.

A recent analysis on international funding going towards Asia and Africa to combat wildlife trade amounted to US $1.3 billion from January 2010 to June 2016. Of this, 46% went towards protected area management to help prevent poaching, 19% to law enforcement, 8% for policy and legislation, and less than 6% went to communication and awareness.

For law enforcement efforts to succeed, there needs to be better coordination and targeted investments. This will help ensure that enforcement agencies have the training to use resources such as forensic science, scanning systems, electronic databases to effectively develop intelligence packages to implicate the offenders and make wildlife trade a risky, high capital cost business, rendering it futile to anyone who wants to get involved.

Join the Conversation