on Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0 .

According to the WHO, 1.8 billion people lack access to safe drinking water worldwide . Poor source water quality, non-existent or insufficient treatment, and defects in water distribution systems and storage mean these consumers use water that often doesn’t meet the WHO’s Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality.

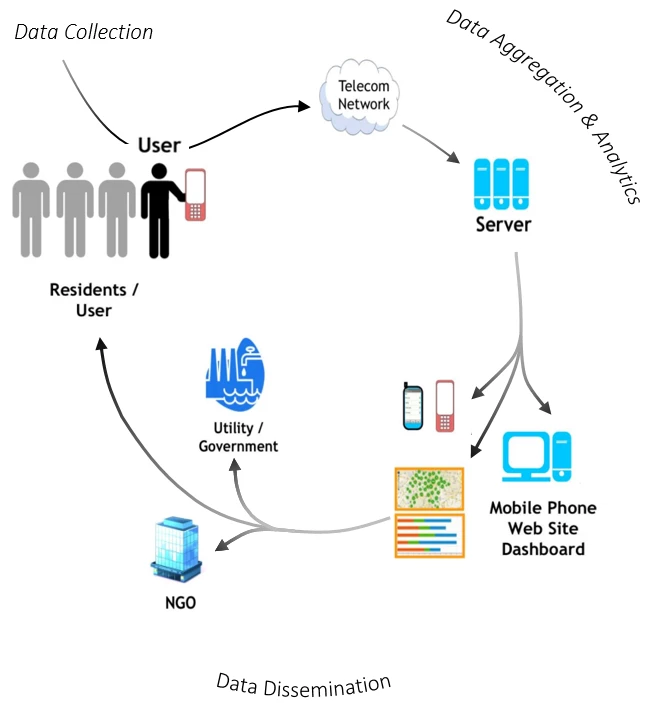

The crowdsourcing framework develops a strategy to engage citizens in measuring and learning about the quality of their own drinking water. Through their participation, citizens provide utilities and water supply agencies with cost-effective water quality data in near-real time. Following a typical crowdsourcing model: consumers use their mobile phones to report water quality information to a central service. That service receives the information, then repackages and shares it via mobile phone messages, websites, dashboards, and social media. Individual citizens can thus be educated about their water quality, and water management agencies and other stakeholders can use the data to improve water management; it’s a win-win.

Palaniappan, M., Srinivasan, V., Ramanathan, N.,

Taylor, J. 2012.“mWASH: Mobile Phone Applications

for the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Sector.”

Pacific Institute, Oakland, California. 114 p.

( Link to full text )

What makes the crowdsourcing framework unique is its focus on developing a more holistic strategy for crowdsourcing. Here are six factors to consider when developing a water quality crowdsourcing initiative:

- You’ll need an understanding of the local context (social, political, and environmental) if you’re going to meet community needs, win the buy-in of key partners, and conduct good environmental science. Project planning with the “Theory of Change” works backwards from the desired outcome and an understanding of the local context to identify the inputs that will help a project succeed.

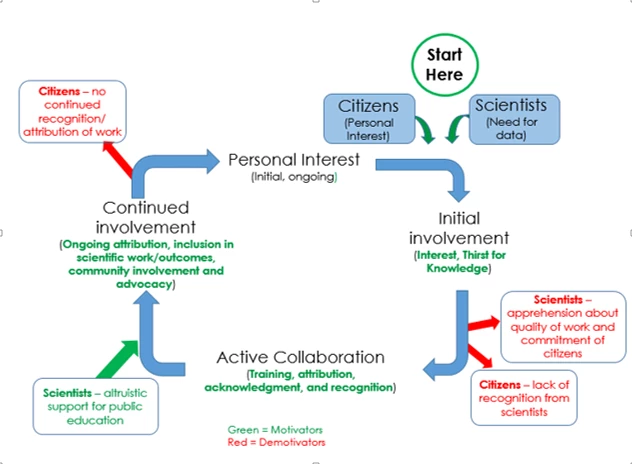

- A collaborative approach to citizen science empowers participants and builds a sense of ownership. Everyday people join a project out of curiosity or in the hope of personal gain. But their ongoing involvement hinges on the feeling that they are making a difference for themselves or for their communities. Projects that recognize volunteers’ contributions, provide feedback, let people see the impacts of their work, and encourage a sense of community involvement are more likely to be sustainable. Distrust, particularly between scientists and project volunteers, undermines citizen science.

- Participants want mobile applications that are not only useful but also easy to use, reliable, responsive, and trustworthy. Data dissemination – via the app or through other channels – should be developed to meet the needs of the various end users. Of course, it’s also important to keep project goals in mind. App development for developing world markets is often hyper-local, because of the control that mobile network operators exert over systems and content. This can limit scalability.

- Don’t forget performance evaluation! From spatial distribution of sampling to water managers’ response times after contamination events, the crowdsourcing framework includes guidance on indicators for measuring both the process and the outcome at every stage.

- Good project design is the sum of social design, technical design, and program design. Social design focuses on relevance and benefit to key actors in a socio-cultural context. This includes an awareness of user perceptions, collaboration, transparency, data privacy, and the like. Technical design focuses on technologies and software, from data collection to data dissemination. Program design considers supporting political/agency infrastructure, performance metrics, and the project’s financial model.

- Which water quality parameters will your project monitor? Available testing technologies, current water quality conditions, and local regulations will all affect your decision. So will the current and future factors that might influence local water quality. These influences may be natural (geology, hydrology, etc.) or anthropogenic (sewage, urban runoff, industrial effluent, agrochemicals, mining waste, etc.). Citizen education about water quality is a major goal , so it’s also important to select parameters that are meaningful and relevant for local users.

Source: Figure adapted from Rotman, D., Preece, J., Hammock, J., Procita, K., Hansen, D., Parr, C., Lewis, D., Jacobs, D. "Dynamic Changes in Motivation in Collaborative Citizen-Science Projects." Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. pgs. 217-226. ( Full text: subscribers only )

Join the Conversation