Desertification & Drought Day

Desertification & Drought Day

As the world marks Desertification and Drought Day today, I thought I’d share my experience working in climate change, specifically, in one of climate change’s most subtle, not so well understood, and deadly manifestations: droughts. Case in point: when images of droughts are shown in news articles, webinar invitations, and the like, all we see is a patch of cracked, dry land. Visually, this does not compellingly convey a drought’s varying characteristics, nor does it illustrate the three main ways droughts impact lives and communities in developing countries:

- Economic and food security impacts include losses in the agricultural sector and drastic production losses in subsistence agriculture and agribusiness. There are also often price increases that cause drops in household food consumption, which then lead to malnutrition and stunting.

- Infrastructure and public health impacts include reduced drinking water supply, cities instituting extreme water rationing, and emergency construction work to secure additional water resources.

- Environmental impacts include biodiversity loss, migration changes, decreased water quality (and increase in disease prevalence), increased soil erosion, and wildfires.

In Southern Africa, the Kingdom of eSwatini (meaning “land of the Swazis”) is vulnerable to numerous natural hazards, but drought is by far the most pervasive and inflicts the most harm to this landlocked Kingdom. Drought events in eSwatini occur every couple of years and cost an average of $US44 million. The 2015/2016 drought season was particularly devastating, costing the government roughly 19 percent of its annual expenditure and equivalent to over 7 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Causes and consequences of droughts do not exist in isolation

During my work in eSwatini, I’ve noticed that communities are dispersed, which makes it difficult to provide safe and affordable access to drinking water and water for crops and livestock. These challenges are only exacerbated when a drought hits, and again, the consequences reverberate across the economy.

This scenario is not unique to eSwatini. The Southern African region is one of the world’s most vulnerable regions from the effects of droughts. From 1980 to 2015, droughts cost the region US$ 3.4 billion, directly affecting well over 100 million people, according to estimates. Looking ahead, the region is expected to become hotter and drier with climate change, a trend that will increase the likelihood for more extreme droughts.

Understanding and addressing recurring droughts in Southern Africa continue to be big challenges. Still, we must acknowledge that drought events can serve as windows of opportunity to proactively build drought preparedness and resilience. With exactly this goal in mind, a multidisciplinary team of the World Bank designed and launched the Southern Africa Drought Resilience Initiative (SADRI) technical support program in 2020, with support from the Cooperation in International Waters in Africa (CIWA). SADRI aims to build analytical and institutional foundations to catalyze national and regional investments in drought preparedness and help to lay the foundations for a more resilient region to the multi-sectoral impacts of drought for the 16 member states of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC). SADRI’s work is structured around three key pillars: (1) Cities, (2) Energy Systems, and (3) Livelihoods and Food Security.

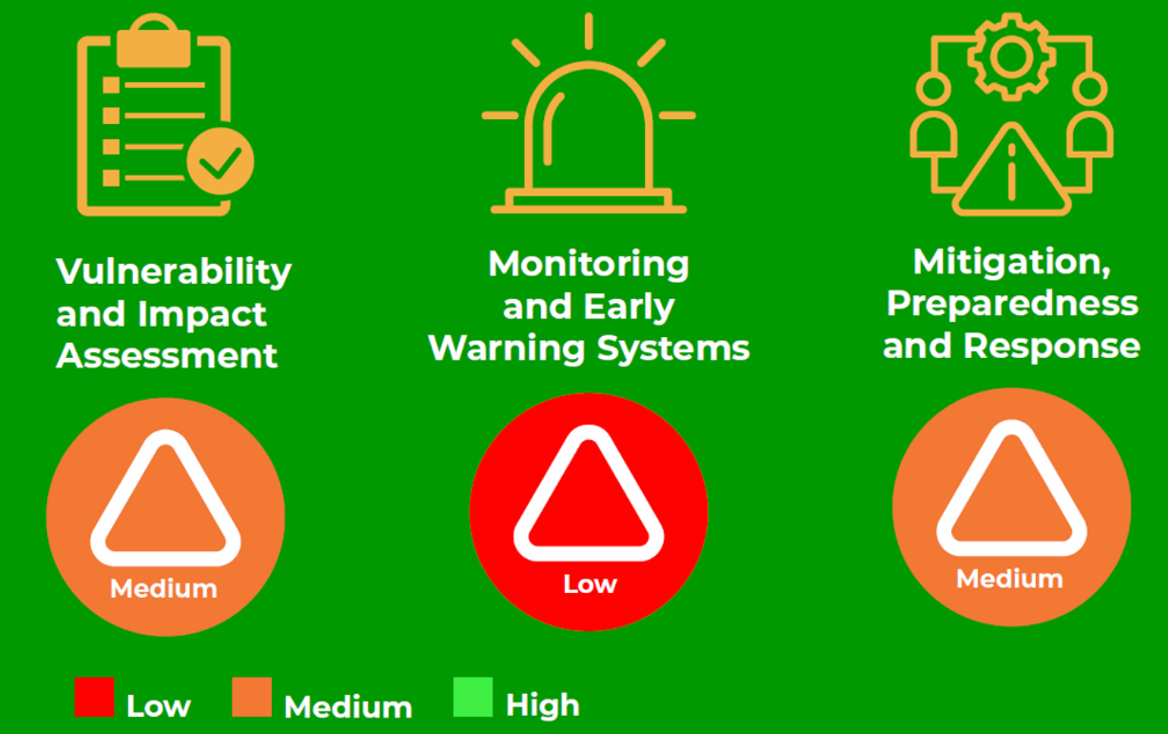

Given that the mechanisms for improving drought preparedness are often regional and transboundary in scope and implementation, SADRI’s approach is predicated upon an integrated drought risk management framework:

The Southern Africa Drought Resilience Initiative’s New Drought Resilience Profiles

One way that SADRI is contributing to the knowledge base and helping to move the region towards a more robust drought policy and management is through the development of its new Drought Resilience Profiles for these 16 SADC countries. These profiles, which SADRI is launching today, featuring Botswana, eSwatini, Lesotho, Namibia, and South Africa (other SADC member states to follow soon after), provide a snapshot of each country’s current drought resilience scenario, as evaluated within SADRI’s organizing framework. They are meant to establish a baseline and to serve as a conversation starter for where and how to move from reactive to proactive drought management. Along with other SADRI efforts taking shape over the next year, these profiles will hopefully pave the way for improved regional planning, collaboration, and action.

“As droughts continue to put the Southern Africa region’s prosperity and livelihoods at risk, these new Drought Resilience Profiles represent an important first step in clearly understanding individual country trends, vulnerabilities, as well as identifying opportunities to build in drought risk resilience measures.” – Anna Cestari, SADRI Program Team Leader

A new path forward for eSwatini in implementing drought resilience-building measures

The situation has improved considerably in eSwatini since the 2015/2016 drought period. What is playing out in eSwatini is in many ways emblematic of what it means for a country to transform from reactive to proactive drought risk management – turning a previous crisis into an opportunity for improvement. Through a combination of efforts across the Kingdom, led by its National Disaster Management Agency, and with the support from the World Bank and other development partners, the government is making significant progress in operationalizing a drought monitor and early warning system, developing drought contingency plans for all its cities and towns, and creating risk financing mechanisms.

By fully embracing resilience-building activities like those being advanced in eSwatini, SADRI hopes to support this paradigm shift more broadly across the Southern Africa region.

Join the Conversation