Do you believe us? You should. A diverse, rigorous range of evidence is accumulating, indicating that open defecation kills infants and stunts the growth of young bodies and minds. New research in biology, medicine, and economics is coming together to resolve old puzzles and to document solutions.

Whether or not you will believe us could be another matter. Evidence alone is rarely enough to attract attention to overlooked causes or to ensure decision-makers select the right solutions. That is where partnerships between governments, researchers like Dean, and programs like WSP, the World Bank’s multidonor partnership program to increase water and sanitation access for the poor, come in – partnerships that can translate evidence into persuasive and useful knowledge that makes for better policy.

The evidence: Sanitation, stunting, and child health

Over a billion people worldwide defecate in the open. This amounts to almost one in five people in developing countries not using any toilet or latrine.

We’re making a big mess. But beyond the ick factor, feces are full of germs. This means that widespread open defecation fills the environment that surrounds children’s homes with ready sources of disease. These germs accumulate in children’s intestines. Not only do fecal germs cause diarrhea, research now points to the greater importance of chronic intestinal disease. Such disease causes changes in the lining of children’s intestines that make it harder for the body to use the nutrients that children eat – even without necessarily manifesting as diarrhea.

Because early-life development is such a critical period, any net nutritional deprivation keeps children from growing to their bodies’ potential heights. And because the same health and nutrition that help bodies grow tall help brains grow smart, this analysis suggests children exposed to open defecation in the environment do not reach their cognitive potentials, either. This leads to an adult workforce that is less economically productive and less healthy – all for lack of putting feces in a safe place.

Height is an important indicator of a child’s well-being. Surprisingly, researchers have long been puzzled by the fact that average height differences across developing countries are not well explained by differences in income. For example, the average person in India is wealthier than the average person in Africa, but Indians are shorter on average. Moreover, this difference cannot be due to genetic factors.

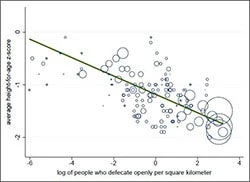

A Policy Research Working Paper by Dean offers open defecation as an explanation. The paper considers several angles, but the key message is found in the figure shown. Each circle represents one county in one year; in fact, they are collapsed rounds of USAID’s Demographic and Health Surveys. The vertical axis is an indicator of the average height of children under three; the horizontal axis measures children’s exposure to fecal germs: how many people openly defecate per square kilometer.

The downward trend is clear: countries where children are exposed to more fecal germs have shorter children. Indeed, open defecation per square kilometer can linearly explain 65% of all cross-country variation in child height in these data. Moreover, open defecation can statistically explain the puzzle of Indian stunting: with both poor sanitation and high population density, Indian children face a double threat.

The rest of the iceberg: Fluency and trust

So, there is growing evidence that policy-makers concerned about children’s health and human capital should concentrate on reducing open defecation. But statistical evidence may not be enough to empower policy change – especially if it sits in academic journals.

The World Bank Group’s global reach allows us, through the range of our financial and knowledge products, to help deliver these important messages from academic research in a timely and intelligible fashion to policy makers, translating high level knowledge into practical solutions which are relevant for the development challenges that policy makers grapple with every day. Clever experiments from the psychology of persuasion and influence demonstrate that more than a good argument is needed to create change.

For example, people are often unimpressed by complex arguments. “Fluency” is the ease with which a text can be mentally processed. Arguments might be disfluent because they are written with unnecessarily big words, or merely because they are printed in a hard to read font. Psychologist Danny Oppenheimer found in an experiment that not only do readers given the same text written more complexly rate the “author” as less intelligent, light printing from a low toner cartridge can have the same effect. What is the connection? Both make a text harder to mentally process.

Oppenheimer won an Ig Nobel prize for documenting, as he puts it, the “consequences of erudite vernacular utilized irrespective of necessity.” But the problem is no joke. Researchers are trained to speak precisely in technical language. For people like Dean, speaking econometrics is actually easier than talking normally – running the risk of missing the chance of delivering an important message in the brief meetings covering many topics with senior policy makers. People often talk about “translating” research into policy; sometimes the translation is literal.

Further, many researchers build a career by publishing many papers on a range of topics. Professionally, they have little incentive to maintain relationships with one department’s ministers and secretaries who will cycle onto other jobs next year. However, research shows that people are persuaded by those we like and trust – especially those with whom we have developed relationships. It is no accident that Danny Oppenheimer, remembered and mentioned above, is Dean’s former psychology teacher.

These are ties that organizations like the World Bank Group, and programs like like WSP can build and maintain. However, for such an organization to be trusted, it cannot offer only glitzy persuasion: it must build a history of responsibly selecting the right arguments to advance. Finally, no statistical argument can fully substitute for the practical wisdom of years of practical experience, which we can integrate with the latest research. Practical experience, gained on the ground with government officials of all ranks, not only serves to ensure that the World Bank Group understands the issues, it builds confidence that we will be there for the implementation.

Impactful evaluations?

More than ever, development economics research is concerned with clear statistical demonstrations of cause and effect. Development organizations are encouraged to conduct “impact evaluations” – often in partnership with academic researchers.

It is important to think carefully about the impact of impact evaluations. We are far from the first to observe that even the best evaluations will have little impact if trusted partners and peers do not make them accessible to policy-makers. Impact evaluation is neither an evaluation of the people implementing a program, nor need it be an assessment of value for money, but rather an additional benefit for all concerned to help shape future activities. Like many organizations these days, we are learning the value of knowledge brokers and evidence producers working together. And as we learn together, we will be spreading urgent knowledge of the alarming consequences of widespread open defecation.

Join the Conversation