Photo Credit: Kathy Eales / World Bank

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 targets “universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all”. However, in Africa’s fast-growing cities, just accessing water is a daily struggle for many poor families . While Africa’s urban population is expected to triple by 2050, the proportion of people with improved water supply has barely grown since 1990, and the share of those with water piped to their premises has declined from 43 percent in 1990 to 33 percent in 2015. Poor families bear the brunt of these inadequacies through poor health, the long time required to collect water, and higher costs when purchasing from on-sellers’.

However, some cities stand out as exceptions. What can we learn from cities and utilities that successfully provide reliable and safe water to almost all of their inhabitants? A study I led recently, Providing Water to Poor People in African Cities Effectively: Lessons from Utility Reforms, analyzed how the water utilities in Kampala, Nyeri, Dakar, Ouagadougou and Durban achieved stand-out performance, and how this made a difference for the poor people in these cities.

In these cities, improving financial performance was critical to effective and sustainable provision. The utilities charged tariffs that recovered their costs and implemented strategies to effectively collect revenues, while ensuring that services were affordable for their customers, especially poor households. A variety of pro-poor strategies were employed, such as carefully designed rising block tariff structures and cross-subsidies for residential consumption, and capping on-sellers’ mark-ups. They also adopted new technologies such as prepaid standpipes and mobile self-metering and payment, and improvised to overcome barriers that prevent them from supplying water to informal areas. For instance, the National Water and Sanitation Office (L'Office national de l'eau et de l'assainissement, ONEA) in Ouagadougou works with small providers to deliver services where the utility cannot due to land tenure rules.

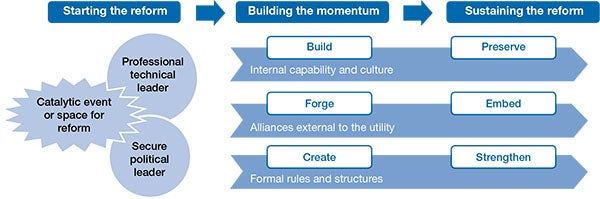

Effective management was essential in achieving the above. In each case, effective management resulted from a reform of the utility, which moved from poor performance to relatively good performance. We also found three key characteristics of successful reforms in each case -- a catalytic event, a skilled and motivated manager, and a confident political leader who supported and protected reform.

In Ouagadougou and Dakar, the catalytic events were water resource shortages; in Durban, the end of apartheid in South Africa created the political impetus to redress service inequalities. Capable utility managers charted the way by addressing urgent needs first, combining technical and financial strategies with institutional reform and winning political support. Outsiders cannot create such conditions, although in some cases development partners have contributed technical advice and financing.

Making reforms sustainable is as challenging as getting them started . As utilities provide better service, they gain more resources and become more tempting targets for predation. Yet, success can also be the first line of defense. Proven competence in service delivery can win support from external stakeholders and raise the political costs of predation. Nyeri’s water utility demonstrates how, when allegations of political meddling surfaced, citizens called to ask how they could prevent it.

Formal structures, such as independent boards and regulators, can help bolster professional corporate cultures, but may be insufficient on their own. In Burkina Faso, ONEA’s performance contract with the government is supervised by a multi-stakeholder committee with customers, nongovernmental organizations, and development partners. Other successful utilities also developed relationship networks with external stakeholders, mobilizing support against predation.

It is possible for rapidly growing African cities to provide their poorest residents with near-universal access to reliable and affordable water. Success is possible even in difficult circumstances – poor water resource endowments, low levels of economic development and seemingly inauspicious governance environments. Where political economy factors can be mustered to enable, support and protect professional management and service provision, combined with the necessary financial and technical support, other cities could similarly extend and sustain water service to poor households.

I am going to present more findings from the study on 30 August at the session “ Water No Get Enemy! Drivers of urban water supply improvement” of World Water Week 2016. Please join us for an in-depth discussion on urban water supply improvement if you will be in Stockholm. Feel free to also share any experience or examples in the comments below!

Related: The Guardian: The African water companies serving the poorest and staying afloat

Join the Conversation