Co-author: Katie Connolly

A recent publication in the health journal The Lancet makes a strong argument for how inequality could be an enabling factor in the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. It argues that people living in poverty are more likely to have chronic health conditions and live in close quarters, thus putting them at a higher risk of contagion. Furthermore, they are less likely to have a safety net and access to adequate healthcare services. In countries across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), which are characterized by deep socioeconomic inequalities, the poorest households are also more likely to experience high economic tolls associated with the pandemic.

These economic disparities are often further exacerbated by a lack of access to adequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services, which in turn increases vulnerability to COVID-19. A lack of on-site WASH services makes practicing good hygiene habits significantly more difficult, thereby increasing the risk of disease transmission. Moreover, as social distancing measures become central to mitigating the spread of the pandemic, those fetching water face increased coronavirus exposure risks by traveling in groups to collect water, gathering at water points and relying on communal sources to retrieve water.

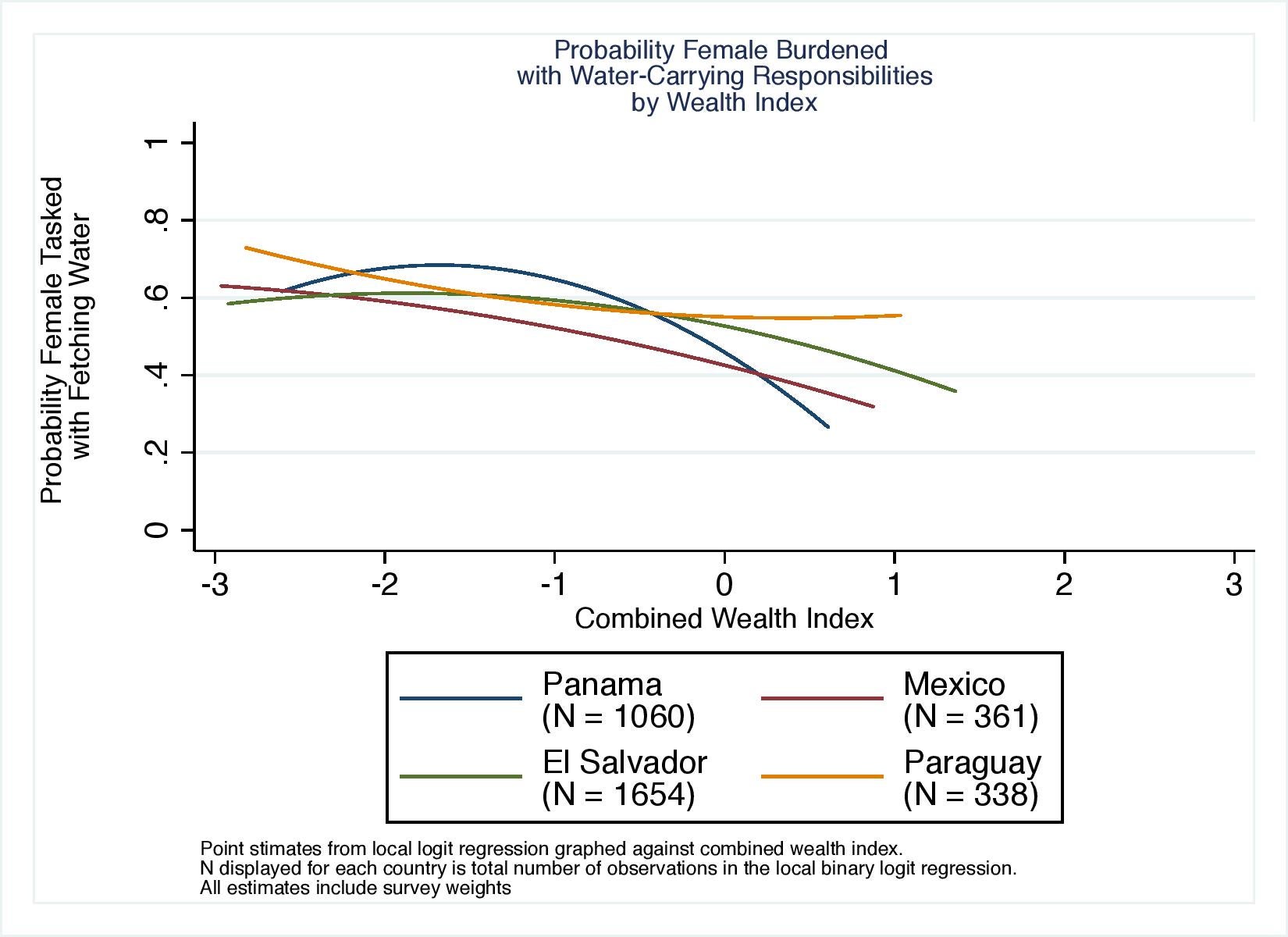

Targeted interventions to increase on-site access to adequate WASH services could go a long way in preventing disease transmission and lessening the economic risks associated with COVID-19, as well as in helping disrupt the gendered dynamics of water-fetching within households. This is especially true among low-income families which, in addition to being most at risk of COVID-19 contagion, are also more likely to burden women with the responsibilities of fetching water (Figure 1).

With the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the needs of women, girls and those in vulnerable populations became mainstreamed into the SDG WASH indicators. These indicators help highlight the numerous gendered disparities in access to WASH services around the globe. One of the clearest ways in which gender inequalities play out in access to WASH services is in how heavily the burden of fetching water falls on women. A UNICEF report, 2017 Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, found that “women and girls are responsible for water collection in 8 out of 10 households with water off premises.”

In a previous blog, we conducted a simple analysis based on the recent Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) in Latin America to illustrate how, across the region, women bear most of the responsibility for collecting water. According to the survey data, when water needs to be collected for a household, it is typically a woman who undertakes this task: 57% of those collecting water in El Salvador, 55.6% of those fetching water in Panama, and 57.9% of those fetching water in Paraguay are women. In Mexico, the burden of fetching water is more evenly divided, with 50.8% of women burdened with water-collecting responsibilities.

To tease-out some of the patterns underlying these relationships, in this blog, we conduct a local-linear regression of the gender of the water-carrying individual against the aggregate household wealth index included in the MICS.1 The wealth index provides a numerical value from poorest (negative values) to richest households (positive values.).

The findings point to strong, negative associations between the gender of the person in charge of collecting water and the wealth of the household. In other words, women are more likely to be responsible for water collection in poorer households. This is a preliminary, non-causal association that’s likely explained by the literature pointing to a strong relationship between gender and income inequality.

In Panama, amongst the poorest families, 63 percent of households task women with collecting water compared to 30 percent of the richest families. In Mexico, more than 60 percent of households on the poorest side of the spectrum have women fetching water, compared to around 38 percent of the richest households. In Paraguay, almost 80 percent of the poorest households task women with the responsibility of fetching water, compared to 59 percent of the richest households (Figure 1).

This association between poverty and gender inequity has been documented in other studies as well. For example, a 2015 flagship study by the IMF found that gender inequality is strongly associated with income inequality and economic growth. According to the study, “an increase in the multi-dimensional Gender Inequality Index (GII)2 from 0 (perfect gender equality) to 1 (perfect gender inequality) is associated with an increase in net inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) by almost 10 points.” Moreover, the same study finds that “an amelioration of gender inequality that corresponds to a 0.1 reduction in the GII is associated with almost 1 percentage point higher economic growth.”

The reality highlighted in this research can also have numerous repercussions on the health and wellbeing of women and girls in the LAC region – particularly in economically disadvantaged households. Read the second blog in this series to learn more about how these disparities negatively impact women on a day-to-day basis, and what steps can be taken to lift the water-carrying burden off of women’s shoulders.

1 The wealth index is built by MICS, and calculated via an aggregate score of: a “household's ownership of selected assets, materials used for housing construction; and types of water access and sanitation facilities.”

2 The United Nation’s Gender Inequality Index (GII) was developed by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 2010, and is a composite measure of gender inequality in the areas of reproductive health (maternal mortality ratios and adolescent fertility rates), empowerment (share of parliamentary seats and education attainment at the secondary level for both males and females), and economic opportunity (labor force participation rates by sex). Source: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1520.pdf

Join the Conversation