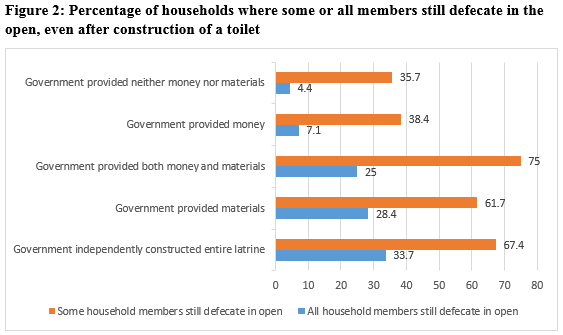

Since 2011, that has changed. As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of people with access to a toilet has more than trebled – from under 20 percent to nearly 68 percent. Of 9,892 Gram Panchayats, the local level of government in India, almost a third – 3,545 – has been declared free of open defecation. That includes all Gram Panchayats in five of the state’s 33 districts, with more set to follow. What has gone right?

This rate of progress is difficult to imagine without top-level political will. Strong support and leadership by the Prime Minister and the personal commitment the state’s Chief Minister to the national Swachh Bharat (“Clean India”) Mission have helped to push sanitation from the bottom of planning meeting agendas to the top. However, that alone does not explain why Rajasthan is outpacing many of its peers.

One significant factor has been state-level institutional reforms that allow districts the freedom to experiment – and the willingness of some District Collectors, the top administrative officials at the district level, to pioneer new ways of working that their peers and the state can pick up on.

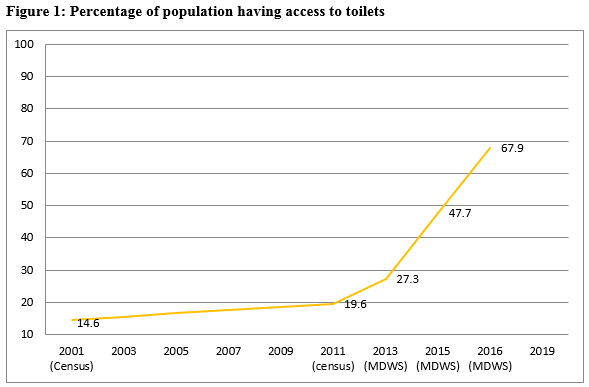

Some of those new ways of working are incentivizing people to construct their own toilets, putting in their own resources, and building toilets that meets their aspirations and needs. Historically, and still currently in much of India, government “incentives” for toilet construction are handed to third-party service providers, who then build toilets for people.

The problem with this approach is that people may not like the toilet that is built for them – it may be poorly constructed, or of a design they would not have chosen for themselves. Across India, unwanted toilets remain unused while their owners continue to defecate in the open.

Some pioneering District Collectors in Rajasthan, learning from other states, started paying the incentives to people directly – but only after they had built the toilet. That means people had to use their own money – or borrow money – to finance the construction upfront. While this may appear to be a more difficult way to achieve results, it has become necessary to convince people about the need of the toilet before a toilet is constructed.

Putting in their own money, even if they know they will be quickly reimbursed a considerable part of the investment by the government, incentivizes people to choose carefully the kind of toilet they want and who to engage to construct it – and to make sure the work is being done to a high standard. That sense of ownership, in turn, makes them more likely actually to use the toilet once it is built.

As shown in Figure 2, the percentage of households where members still defecate in the open after a latrine is constructed is lowest when the household meets the entire cost, and highest when the government independently constructs the latrine. But many households cannot meet the entire cost – and when the government provides just money, without materials, the result is almost as good.

One reason is the systematic capacity building of District Resource Group (DRG) members. These are the “sanitation storm troopers” who run behavior change campaigns – going into villages to persuade villagers that open defecation is a threat to their health and dignity.

A district of one or two million people might have 50-100 DRG members. In groups of three to five, they go into villages, typically for three days at a time, to “trigger” the villagers and encourage them to set up nigrani (“vigilance”) committees.

Members of these committees patrol the village at the times of day when people typically defecate in the open, which makes the practice feel more socially unacceptable. Subsequently, DRG members follow up with visits to check on progress.

The work of DRG members in Rajasthan is made more effective by careful selection procedures – with tests of natural aptitude in situations such as group discussions – followed by initial training, and exchange visits to learn from their peers in other districts. Mobile videos are also used to share good practices.

Enabling policies and guidelines at the state level supported all these changes. For example, operational guidelines and standard operating procedures issued by the state government encourage approaches that promote behavior change rather than mere toilet construction. The state government encourages districts to engage DRG members and nodal officers for behavior change campaigns.

Another policy which has helped to make sanitation a priority for local leaders is making toilet construction mandatory for contesting in local government elections. Regular workshops for District Collectors, led by the Chief Minister, help to share good practices and motivate more Collectors.

Technical assistance from the World Bank since 2011 has helped to catalyze Rajasthan’s progress. For example, the early champions among District Collectors were inspired by learning visits to Himachal Pradesh facilitated by the World Bank – and supporting them in their districts created success stories the state could then showcase to other districts.

More than half of Rajasthan's districts have now initiated community-led campaigns on sanitation , and the state government has ambitions of becoming entirely free of open defecation by 2018 – a target that would have seemed unthinkable just a few years ago.

Join the Conversation