Four photos of a virtual experience, showing animated people in a store purchasing objects

Four photos of a virtual experience, showing animated people in a store purchasing objects

Tax collection isn’t easy for most governments even in normal circumstances. In times of crisis, economic activity – and thus tax revenues – take a hit, and the role of the state to protect vulnerable individuals and businesses becomes even more crucial. However, tax compliance has become even more complicated during a global pandemic with high levels of uncertainty.

Even for model taxpayers, COVID-19 shifted priorities toward more immediate concerns such as health, childcare, and work-related issues. Our ability, willingness, and motivation to comply with citizen obligations shifted. It’s not surprising that taxes would fall under the same logic.

How can we keep things moving when everyone’s attention is directed elsewhere?

Behavioral insights have proven to be a useful tool to encourage voluntary compliance in challenging environments. Our experience applying behavioral insights to tax compliance in Armenia highlights challenges to adopting this set of tools, but also opportunities in this “new normal.”

In late 2019, the World Bank began working closely with the tax authority in Armenia – the State Revenue Committee (SRC) – to incorporate behavioral insights into strategies to encourage voluntary tax compliance. The approach involves strategically engaging with taxpayers in behavior change -namely through simplification of technical language, clear calls to action, and highlighting typically overlooked aspects of taxes (e.g., the enforcement capacity of the tax authorities or how taxes finance public goods).

The World Bank and the SRC team identified improvements to existing notifications to taxpayers across tax systems (Value Added Tax, Turnover Tax, and Corporate Income Tax) with inconsistencies in their tax returns that warranted a correction. The objective of this exercise was to identify the best language to encourage taxpayers to correct erroneous returns.

Tax experiments were conducted (independently for each tax system) in the summer of 2020 at a time when lockdowns were still in place, business activity constrained, and a geopolitical crisis developing. All targeted taxpayers (a total of 7,857 across all systems) were sent a notification. One-third were randomly assigned to receive a behaviorally-informed letter centered on the enforcement capacity of the SRC, one-third a behaviorally-informed letter emphasizing the role of taxes in financing public goods, and the remaining third a standard letter.

Our results highlight the challenges of nudging during the pandemic, but revealed the promise of certain triggers to induce compliance among taxpayers. Less than one in three taxpayers targeted by the notifications made the requested correction to their tax returns, which was highly sensitive to the tax system being targeted. We found that the rate of correction for taxpayers targeted for the VAT was significantly higher (40 percent, compared to 25 percent for Turnover Tax and 19 percent for CIT).

How tax authorities communicate matters

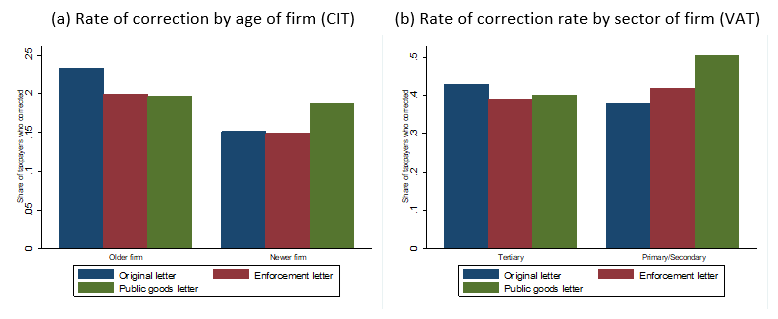

The letter emphasizing the role of taxes for public goods performed significantly better, particularly for select segments of taxpayers. For example, taxpayers were 50 percent more likely to submit a correction to their return by the stipulated deadline when assigned the public goods version of the letter than a regular letter. Moreover, the likelihood of correction differed significantly by the type of taxpayer and tax system: younger firms targeted under the Corporate Income Tax were more likely to correct their return if assigned the public goods letter. The same was true for those in the primary and secondary sectors targeted under the VAT (Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Correction of tax return by treatment assignment and taxpayer type

The team didn’t stop there: we conducted an online survey experiment among the adult population and found that engagement strategies can have important implications for tax morale. An animated video (Figure 2) highlighting the role of taxes in society found that this approach can have significant impacts on tax morale relative to a simple compliance message.

Figure 2. Snapshots of animated video on the role of taxes

Behavioral insights can be a useful tool to increase tax compliance, even during crises. Armenia does not stand alone in this regard , as recent evidence from Albania suggests. In addition to the substantial work of the World Bank and the Government of Armenia, a continued exploration of innovative solutions based on behavioral science (beyond nudging) is in order in Armenia and beyond, particularly to push the envelope about what is possible during crises.

This blog summarizes a larger body of work on applications of behavioral insights to tax compliance in Armenia under the Governance Global Practice-led project “Support to tax administration and policy leadership (STAPL)”. The project was implemented by the World Bank in collaboration with the UK Government’s Good Governance Fund.

Join the Conversation