Delivering pension or disability services may sound mundane, but if you have seen the recent award-winning movie, I, Daniel Blake, it is anything but. As the film poignantly demonstrates, treating citizens with respect and approaching them as humans rather than case numbers is not just good practice -- it can mean life or death. In the film, Mr. Blake, an elderly tradesman with a heart condition, attempts to apply for a disability pension. In the process, he navigates a Kafkaesque maze of dozens of office visits, automated phone calls, and dysfunctional online forms. All of this is confusing and often dehumanizing.

Modern reform-minded governments try to re-imagine public service delivery from the point of view of service users, as the costs of failing to do so are too high. These governments do not take the dignity of their citizens lightly and look for ways to improve administrative service delivery. Putting citizens at the center means increasing convenience , striving for minimal wait times, treating citizens politely, and reducing red tape and corruption. In a growing number of countries, citizens can now obtain everyday necessities such as drivers’ licenses or passports with both speed and smiles.

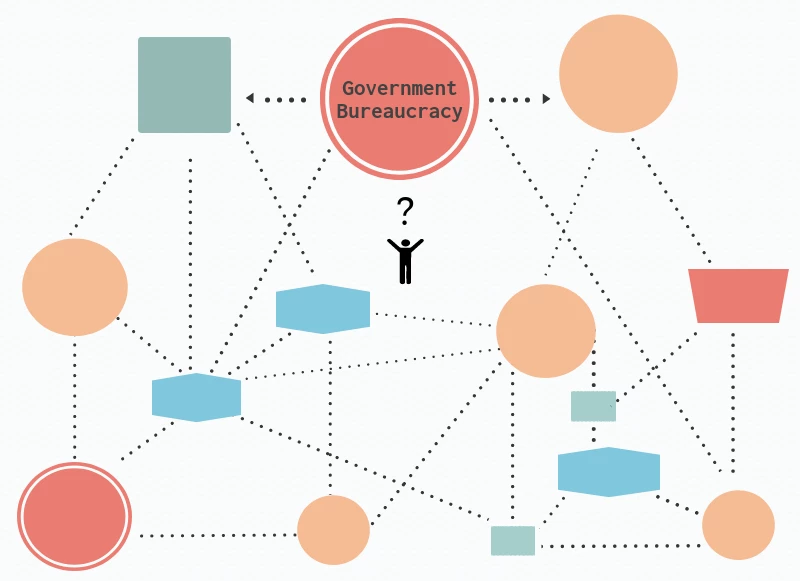

In recent years, a trend of providing public services through One-Stop Shops has taken hold worldwide . These centers act as a citizens’ primary contact point for accessing multiple public services and information, and vary in both scope and form. Some deliver a variety of services under one roof, others focus on a single sector, such as judicial or transport services. They can be operated by a central government or by municipal authorities and can target different groups such as citizens or firms.

A recent three-day peer-learning event, held in Singapore and Johor Bahru, Malaysia, provided the opportunity for practitioners to exchange their experiences with different models of One-Stop Shops. The workshop— co-organized by the UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence, World Bank Group Global Knowledge and Research Hub in Malaysia, and Regional Hub of Civil Service in Astana—brought together practitioners from 29 countries around the world to talk about the future of citizen-centric service delivery and take stock of successes, challenges, and lessons learned from setting up One-Stop Shops.

The main takeaways include:

- Political leadership, government coordination, and a phased approach to implementation are critical. For reforms to be sustainable, high-level reform champions and steering committees must support coordination and communication among stakeholders, ensuring government ownership at all levels.

- Take a problem-driven approach and understand the broader context of the reform. When introducing One-Stop Shops, it is important to define one or more problems that the One-Stop Shops are expected to solve. This could include reducing time and administrative burden for citizens and businesses, improving access for rural and disadvantaged citizens, or reducing corruption. Depending on the underlying mix of problems, the design and purpose of the One-Stop Shops will differ. While factoring in the problems specific to the country, One-Stop Shops must also complement the governments’ broader administrative reform agenda.

- Implementation: feasibility and operational architecture. Once the problem and the objectives have been defined, countries with successful One-Stop Shops conducted a study to show the feasibility of this reform. The feasibility study usually explores whether business process re-engineering or simplifying administrative processes are needed, whether any adjustments to the policy and legal frameworks are required, and how the One-Stop Shop will be financed. After that, the government should choose the operational architecture for implementation. This means reviewing the options for integration of the available IT systems; securing broadband connectivity to enable data exchange across agencies; and ensuring interoperability so the databases can be used by different agencies and service providers. Significant improvements in the speed and quality of service delivery through One-Stop Shops can only be achieved with digitized databases and some existing interoperability.

For an in-depth analysis of the proceedings from the international peer-learning workshop on One-Stop Shops earlier this year, please see the resulting report.

Tweet these:

- In film @idanielblake one man struggles w/ bureaucracy. How can we make gov more efficient?

- Gov practitioners from reform minded countries get 2gether to improve service deliveries for citizens

- Humility can get lost in a govt bureaucracy. Citizens deserve respect and quality services

- Govts are increasingly using One-Stop Shops: citizens can have multiple govt services under one roof

Join the Conversation