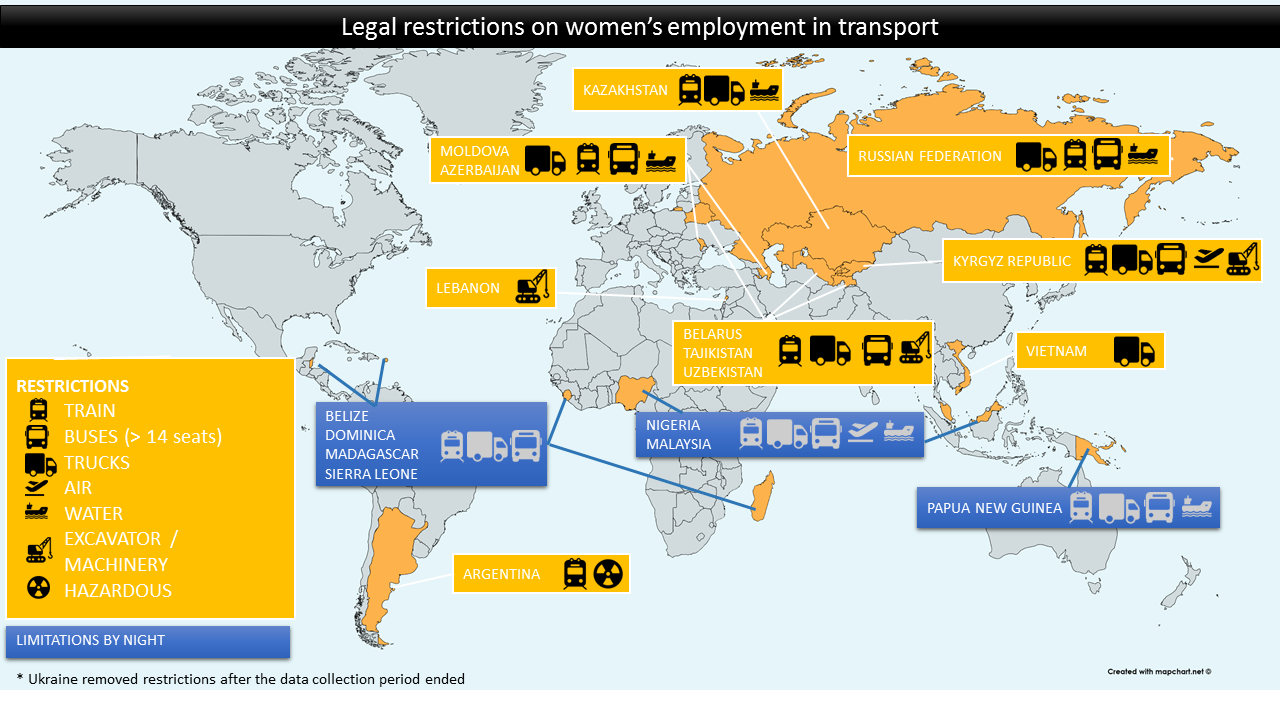

Starting this month, an estimated 9 million women will be able to get behind the wheel in Saudi Arabia after the historic announcement in September last year lifting the ban on women from driving. While international attention has often focused on the driving ban on women in Saudi Arabia, it has often missed the fact that women in several other countries are legally debarred from certain driving jobs. The World Bank’s recently released Women, Business and the Law 2018 report finds that 19 countries around the world legally restrict women from working in the transport sector in the same way as men.

In countries such as Belize, Dominica, and Nigeria, women cannot work in the transport of goods or people at night, a likely holdover from colonial-era laws based on outdated International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions. In countries such as the Russian Federation, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, numerous transport sector jobs are off-limits to women. If a woman in these countries wants to be a train, truck, metro or bus driver, she may find that the law precludes her from doing so solely because of her gender.

Why reform?

Laws that restrict women’s employment are internationally recognized as an affront to human rights. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the ILO’s Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention encapsulate the principles of freedom from discrimination in the field of employment and the free choice of profession and employment.

Apart from traditional human rights arguments, there is ample evidence showing that such laws are stunting economic growth and hurting businesses. Women, Business and the Law finds that where legal restrictions on women’s employment exists, less women work and the gender pay gap is wider.

In the case of Saudi Arabia, part of the government’s motivation for the landmark change in policy is economically driven. According to the New York Times, Saudi leaders hope that the new policy will help the economy by increasing women’s participation in the workplace: only 22% of women participate in the labor force as compared to 79% for their male counterparts in Saudi Arabia. However, it is still unclear whether women will be allowed to work as professional drivers.

The business case for hiring women in transport sector jobs is also strong. Improving gender balance can help transport companies meet their staffing needs by ensuring that they are not missing out on half of the population in their recruitment practices. It can also improve their customer service by putting both women and men in public-facing roles, such as driving, as well as enhance their public image: companies with a more equal balance of women and men can project a more progressive image that is representative of their customer base.

Changes are coming

The good news is that more reforms are expected. In December 2015, Ukraine repealed a Soviet-era regulation that barred women from driving trucks, trains, locomotives, trolleys and certain types of buses, along with almost 450 other jobs. And just this past April, the Russian Ministry of Labor issued a draft regulation to potentially replace Resolution No. 162 of 2000—which bans women from 456 professions—that narrows the list of prohibited jobs to 35 categories. Truck drivers, metro train driver and bus drivers are notably missing from the list.

Indeed, governments are taking note that women’s equal participation in the transportation sector can yield gains for all. Individual transport companies are also starting to realize that gender inequality has negative implications for their customer service, revenue generation and operational efficiency. At the same time, removing legal restrictions is just a start that needs to be followed by a whole range of actions tackling other perhaps less visible but deeply embedded barriers that impede women’s access to employment in the sector. This includes addressing gender stereotypes, which have a strong influence on the education choices that women and men make and which see driving positions as a ‘male’ occupation, as well as workplace health and safety issues ranging from lack of appropriate facilities to sexual harassment in the workplace. To keep the momentum going, it is important to continue drawing attention to the progress being made on this front and to highlight human rights, economic and business arguments for having more women in the sector.

Join the Conversation