Accelerating Poverty Reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa Requires Stability. Credit: Stephan Gladieu

Accelerating Poverty Reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa Requires Stability. Credit: Stephan Gladieu

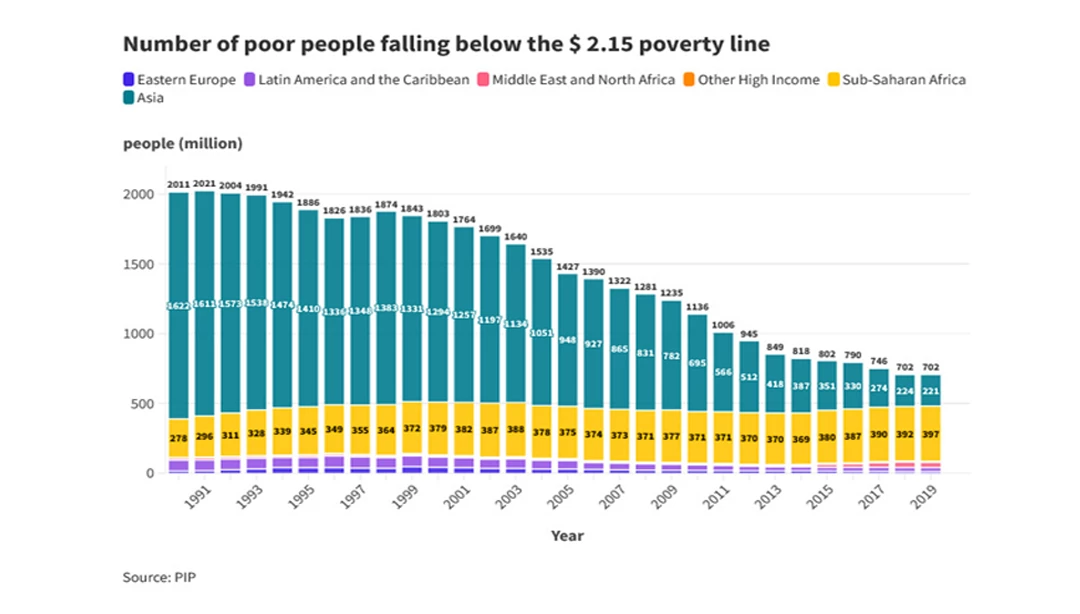

The last 30 years have seen dramatic reductions in global poverty, spurred by strong catch-up growth in developing countries, especially in Asia. In 1990, the number of people living under the $2.15-a-day extreme poverty line in Asia exceeded 1.6 billion. By 2019, this had reduced to 221 million. Globally, over the same period, 1.3 billion people were lifted out of extreme poverty.

The success of global poverty reduction is dominated by China and India where strong economic growth drove poverty down rapidly. In other parts of the world, poverty trends were more disappointing. In Latin America, poverty fell much more gradually, while in the Middle East and North Africa it fell until 2013, after which it rose due to a combination of conflict following the Arab Spring and disappointing economic growth.

Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced low economic growth per capita, a very slow decline in poverty incidence, and the number of people living in extreme poverty has been rising steadily. As a result, extreme poverty is increasingly concentrated in this region. In 1990, 14% of the world’s poor lived in Africa, by 2019, 57% of the world’s poorest lived in Sub-Sahara Africa.

Learning from the Asian example, it seems self-evident that attaining the objective of eradicating poverty requires accelerated economic growth, in the Middle East and North Africa and especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

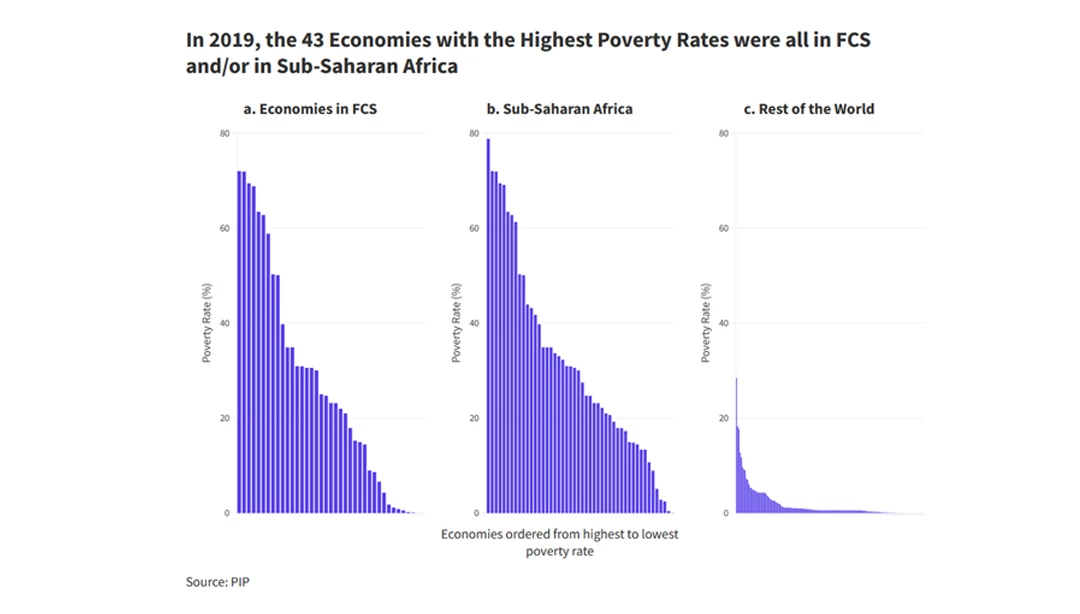

Within Sub-Sahara Africa, poverty is also increasingly concentrated in Conflict Affected and Fragile States (FCS). In 2019, 50% of the poor lived in Fragile and Conflict Affected States. By 2030, an estimated two third of the world’s poor will live in FCS (Corral et al. 2019). This, even though FCS comprise just 6% of the global population, although that percentage is changing as more countries fall into fragility.

The joint importance of fragility and being in Sub-Sahara Africa is illustrated by the finding that the 43 countries with the highest poverty rates in 2019 were either in an FCS or in Sub-Sahara Africa.

Economic growth is premised on stability, and the fact that China and India were stable for the past 30 years is easily taken for granted.

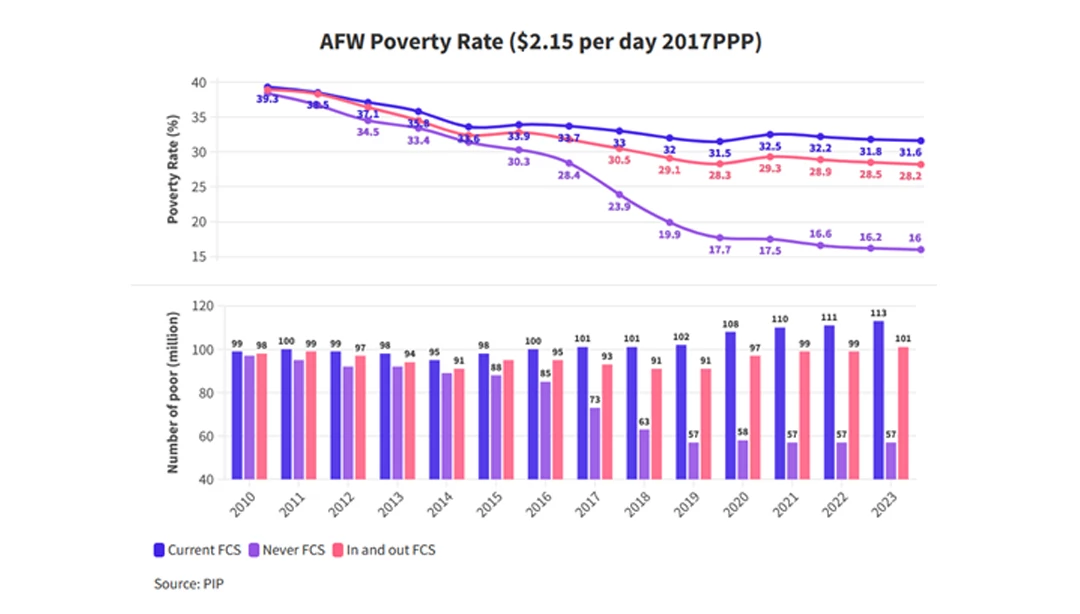

The importance of stability for future poverty reduction can be seen from the graph below, prepared for Western and Central Africa. Countries that managed to avoid fragility (Benin, Cabo Verde, Gabon, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea and Senegal) managed to steadily reduce poverty. Relative to countries that are presently fragile, or that moved in and out of fragility, stable countries reduced poverty by an additional 15 to 20 percentage points.

Stability, by the way, goes beyond an ability to maintain peace. Macro-fiscal and debt sustainability are equally critical, as Ghana which recently defaulted on its external debt unfortunately shows. Poverty (at $ 2.15) increased from 25% in 2020 to 33% in 2023.

The implication is clear. Future poverty reduction will increasingly be premised on the ability to ensure stability, as stability is a precondition for economic growth and poverty reduction. In a world in which conflict and instability are on the rise, and debt distress is rising, this is a sobering realization and bad news for the global community’s ability to eradicate poverty anytime soon.

Join the Conversation