As African countries accelerate the deployment of COVID-19 (coronavirus) vaccines, the issue of vaccine hesitancy looms. Globally, there has been a rise in general vaccine hesitancy but especially towards COVID-19 vaccines. In Africa, hesitancy must be viewed in the context of significant vaccine shortage; hesitancy does not explain fully the low vaccination rates in Africa. The slow vaccine rollout on the continent is due to supply constraints, structural issues, and logistical barriers.

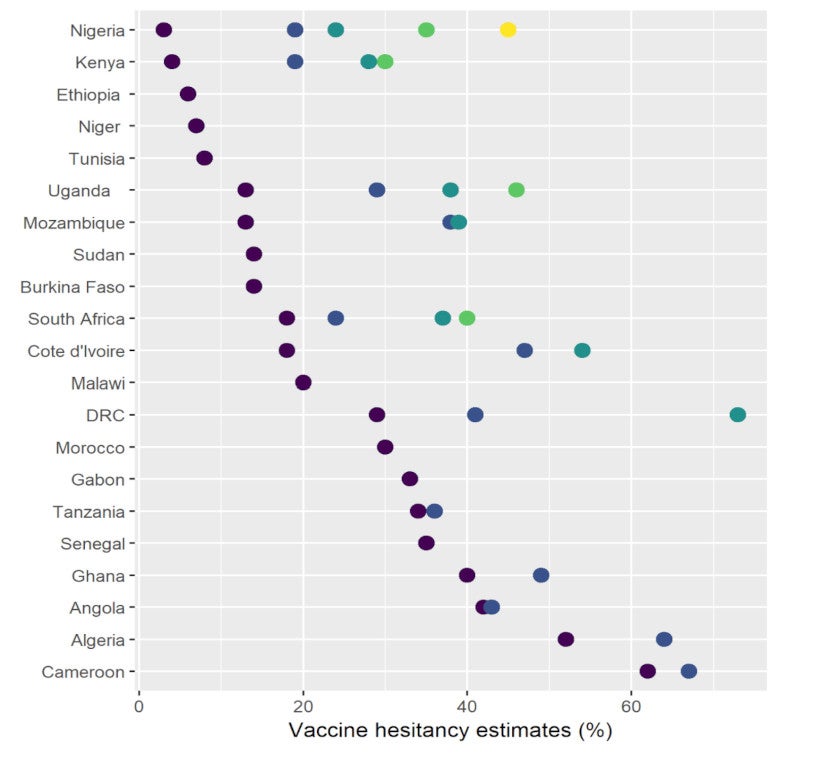

The critical question is how to increase both supply and demand. A 2020 Africa Centre for Disease Control (Africa CDC) survey in 15 countries found that while 79% of respondents would take a COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine hesitancy ranged from four to 38% (see figure 1 for more estimates). In a recent five-country Afrobarometer survey six out of 10 citizens in Benin, Liberia, Niger, Senegal and Togo were hesitant to get vaccinated.

In Africa, there are multiple drivers of vaccine hesitancy . Concerns about safety, side effects, and effectiveness are widespread—and observed among health workers in Zimbabwe, Ghana, South Africa, Kenya, Sudan, and Ethiopia. The Africa CDC survey noted that respondents viewed COVID-19 vaccines as less safe and effective than other vaccines, similar findings have been observed in Uganda, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Mozambique, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and South Africa. The suspension of AstraZeneca’s roll out in some European countries, the South African data on its effectiveness and the temporary suspension of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the United States to evaluate reports of blood clotting, affected confidence in COVID-19 vaccination. Ultimately, AstraZeneca’s vaccine was refused by several African countries.

Access to social media has facilitated the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories. In the Africa CDC study, people with high levels of hesitancy were more likely to use social media and be exposed to disinformation. Half of those surveyed in South Africa believed the virus was linked to 5G technology. In another South African study, approximately a third of those who would refuse the vaccine trusted social media as a primary source of information. A small study in Addis Ababa showed that hesitancy was 3.6 times higher among those who received their information from social media compared to those who relied on television and radio.

Trust in one’s government influences vaccination uptake. In West Africa, Afrobarometer reported high levels of mistrust in governments’ ability to provide a safe vaccine. Those who did not trust their government were five to 10 times less likely to want to be vaccinated. In Ghana, 40% of those who are unwilling to be vaccinated cited mistrust of the government while in South Africa, those who believed the president was doing a good job were more likely to be vaccinated.

Religious beliefs also inform vaccine acceptance. Close to 90% of individuals surveyed in Niger and Liberia said that prayer was more effective than the vaccine. A recent Geopoll survey in six African countries showed religious beliefs as key determinants of hesitancy.

Perceptions of the magnitude of the threat posed by COVID-19 and the risk of contracting it influence behaviour. In DRC and Côte d’Ivoire, people who did not believe COVID-19 existed were unlikely to want to be vaccinated. Vaccine acceptance among people who knew someone with a prior COVID-19 infection was 13% higher than those who did not. Though, when respondents knew someone who had been infected with COVID-19, they still underestimated the threat posed by the virus.

Mistrust of vaccines developed in Western countries is not new in Africa . It is rooted in the history of unethical Western medical practices on the continent where early efforts to address disease diminished trust in Western medicine and led to underutilization of health services. Approximately 43% of those surveyed by the Africa CDC 15-country study believed that Africans were being used as guinea pigs in vaccine trials. Similar findings were noted in DRC; and, a 2021 survey in Addis Ababa hesitancy was associated with the belief that the vaccine was a biological weapon from developed countries to control population growth.

But, perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines are not static : repeated data collection using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies is necessary to monitor changes over time. Between November 2020 and April 2021, the GeoPoll survey recorded increases in hesitancy in Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, and DRC. In Mozambique, hesitancy decreased in late 2020, only to increase in early 2021. While in Ghana hesitancy decreased from 38% in August 2020, before vaccines were approved, to 17% in April 2021 after the first batch of vaccines was delivered.

As vaccine supply increases and communication campaigns expand, changes in hesitancy are being observed. This needs to be constantly monitored to develop consistent and effective communication strategies that address the challenges posed by new variants and more divergent views on COVID-19 and vaccines continue to flood social media.

Figure 1 – Compilation of available estimates for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in different African countries (some countries have multiple estimates).

Join the Conversation