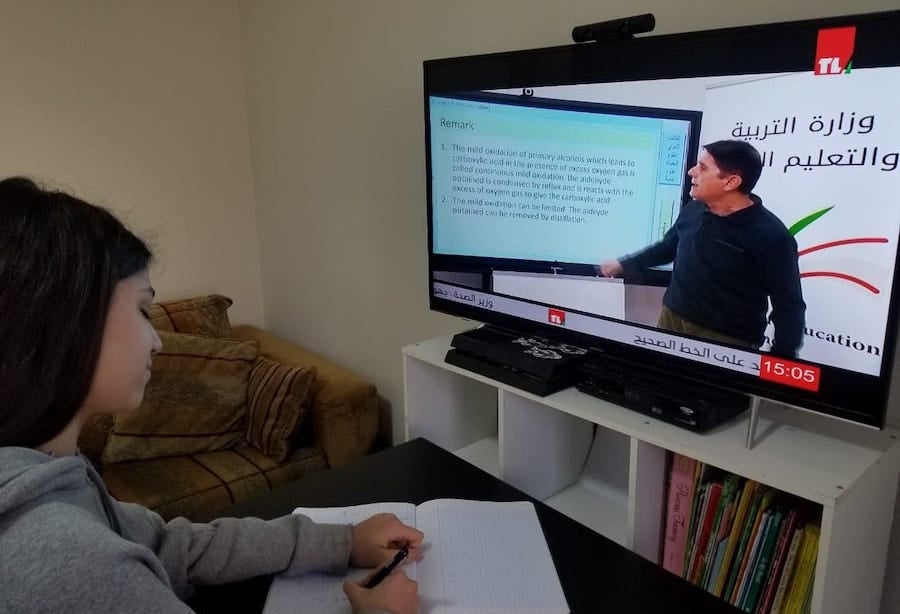

Des étudiants libanais participent à des programmes d’enseignement à distance.

Des étudiants libanais participent à des programmes d’enseignement à distance.

As the COVID-19 global pandemic has swept across the globe in recent weeks, countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have not been spared. In an effort to curb the spread of infections, governments across the region began restricting movements and closing schools in early March. Today, educational institutions remain shuttered and over 100 million students are out of the classroom.

Preliminary modeling projections point to a drop in learning outcomes, similar to what’s been documented in schooling analyses that show as much as one third of school-year learning is lost over the summer break. In a region that boasts the highest education intergenerational mobility in the world, schooling is serious and steeped in building knowledge for high-stakes exams that can make or break life-long ambitions.

To mitigate the impact of school closures, learning in MENA has gone virtual, moving online where connectivity can be established, and using television, radio, and paper-based approaches where internet access is limited. Countries like Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco are among those leading the charge, employing multi-modal approaches and building innovative partnerships overnight to deliver learning in a new environment.

The process has not been easy and the transition is far from seamless. Across the region, telecom infrastructure is inconsistent. A number of households still do not have laptops, tablets, or smartphones accessible to students for regular learning. Teachers have had little or no time to acclimate to new teaching tools and are now creating curricula and structuring remote classes. They are finding it difficult to engage and assess students remotely. The learning environment has shifted for parents, as well, many of whom were deputized overnight as homeschoolers in systems with which they may not be familiar.

Despite these inconveniences, these efforts have the potential to expand the flexibility of delivery education in MENA. Here are some examples of how:

- Homegrown innovations are becoming mainstream tools. Education technologies (edtech), largely considered supplemental add-ons to teaching, are on the rise. Mobile apps like Rawy Kids from Egypt or Kitabi Book Reader from Lebanon, or Sho'lah, and Loujee — "smart" Arabic toys aimed at learning-through-play (Arab News 2016) have emerged as useful tools introducing students to different means of learning.

- A stronger move towards cross-collaboration. Collaborations between ministries and service providers, across private entities and countries, have proliferated in recent weeks, delivering a collective greater good. In Jordan, an education portal called "Darsak" was developed through a partnership between the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship, and a private enterprise called Mawdoo3. The content, in the form of lessons tied directly to the Jordanian curriculum, was crowdsourced from a number of educational organizations including Edraak, Jo Academy and Abwab. The result is a one-stop-shop that delivers weekly-scheduled classes for all grades.

In a show of cross-country collaboration, Egypt is granting users from neighboring countries access to the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (through study.ekb), an online government library housing resources like K-12 grade lessons for educators, researchers, and students. In both Egypt and Morocco, authorities have successfully negotiated a partnership with telecom enterprises allowing access of their educational platforms to all students without internet or data fees.

In Lebanon, the Beirut Digital District Academy has teamed up with the World Bank Skilling UP Mashreq Project and Code.org to offer free coding courses in English, French and Arabic to students ages 6 to 18 across the country.

- New ways of coaching, teaching, and learning are showing the potential to close the inequity gap. In Lebanon, the Ministry of Education and Higher Education is training teachers in the use of Microsoft Teams to run online classes, receive and share information, and offer support. Coaching of teachers, normally carried out face-to-face, is moving online, allowing teachers in hard-to-reach areas to benefit equally as those in metropolitan, more accessible locations.

- Learning by doing in the virtual world is reaching new frontiers. Without regular real-time instructional support, students are increasingly using multiple sources for understanding new concepts, and relying on teachers as coaches, rather than instructors. In essence, this is the critical thinking approach to learning that has been long overdue in MENA — a new framework for education structured to deliver 21st century skills and lifelong learning for its graduates to compete in tomorrow’s economies.

While it remains to be seen when some countries will reopen and when it will be safe to bring students back to schools, these developments are signs that education delivery could change for the long-term. In MENA, these changes should be welcomed.

Join the Conversation