MENA Blog

MENA Blog

One striking feature of the recent economic history of the Middle East is high-income Gulf economies financing the persistent external imbalances of its geo-strategically important neighbors. This column asks what happens when, as a consequence of the technological disruptions of the global fossil fuel market, the current account deficits of key countries in the region are no longer sustainable.

When Lebanon faced reluctant financial markets earlier this year, Qatar lent a helping hand. "We wish stability and prosperity for the Lebanese republic and the Lebanese people, and that the Lebanese economy will recover. The region needs a strong and prosperous Lebanon," said Qatari Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani in a statement after his country agreed to buy $500 million of Lebanese government bonds (Reuters, 2019a).

Soon thereafter Lebanon’s sovereign bond spreads fell. A few days later, Saudi Arabia’s finance minister declared the country would support Lebanon ‘all the way’ (Reuters, 2019b). Months later, Lebanon’s sovereign bond spread rose again after the newly formed government was unable to enact fiscal and structural reforms quickly.

This episode is emblematic of an economic history of the Middle East characterized by high-income economies financing persistent external imbalances (current account deficits) maintained by geo-strategically important economies.

Thanks to capital inflows from official sources, many economies of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) could afford persistent trade and current account deficits. Many oil-importing countries – such as Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia – have been running large and persistent trade and current account deficits for more than a decade. Hence a fundamental macroeconomic question for the region is whether this model of surplus economies financing the deficits of their neighbors is sustainable.

The answer is probably not in the long run, although run-of-the-mill emerging market crises are unlikely to occur in the short run. Technological breakthroughs in renewable energy and in shale oil are holding oil prices down and hence limiting the region’s ability to mobilize regional savings.

The long-term equilibrium price of fossil fuels is expected to remain low and, with it, the capacity of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members’ current account surpluses. The oil price decline over the period 2015-17 is an instructive prelude. Average current account balances for the GCC countries dropped from a large average surplus of 16.5% of GDP between 2000 and 2014 to a small deficit of 0.7% of GDP during 2015-17 (see Figure 1).

In addition, MENA’s historical growth record is poor. Despite the World Bank forecast of a modest uptick in regional GDP growth for 2019-21 (1.5% in 2019, 3.4% in 2020 and 2.7% in 2021), MENA’s growth rate will remain comparatively low.

Figure 2 shows average growth rates in per capita GDP for each MENA economy (represented by blue diamonds). It also shows the median growth rate of their corresponding income group (represented by red horizontal lines). Most of them are projected to grow at a slower pace than a typical (median) country in their corresponding income group during 2018-21. Indeed, this pattern of comparatively low growth has persisted for decades in the region (see Figure 2).

What factors could drive both low growth and persistent current account deficits? In Arezki et al (2019), we argue that, for MENA, it is low labor productivity. We examine the fundamentals of current account balances, namely demography, forecast growth, aggregate labor productivity (relative to the United States), commodity prices and exchange rate regimes. This analytical approach is similar to that used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2013) but focuses on a smaller, more clearly exogenous, subset of ‘fundamentals’.

We find that if the capital account is completely closed, a 1 percentage point decrease in relative productivity compared with the United States is associated with a 0.16 percentage point decline in the current account balance. Note that in the last ten years, MENA’s labor productivity relative to the United States has been declining, from about 56% in 2007 to about 46% in 2017. (Opening the current account worsens the current account deficit as capital inflows are expected to be higher.)

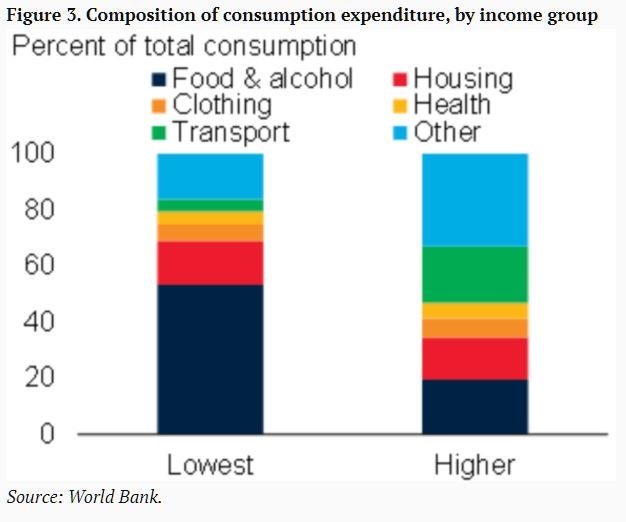

Our predictions suggest that many MENA economies have current account balances that cannot be explained by fundamentals (see Figure 3). In other words, after all the long-term fundamentals are considered, these countries’ current account balances are still statistically negative.

The unexplained component is calculated as the residual from the main specification of the World Bank MENA chief economist’s model, which is the difference between the actual current account balance and the predicted current account balance. The upper and lower bounds of the unexplained current account balance, as well as the forecast to 2020 are shown in Figure 3.

Nevertheless, the good news is that MENA’s capital account composition seems less susceptible to ‘sudden stops’ of capital inflows, because it consists largely of the more stable inflows of foreign direct investment and official assistance, and much smaller portfolio investment inflows compared with countries from corresponding income groups. Hence our initial statement that classic balance of payments crises are unlikely to occur in MENA in the short run. On the other hand, they rely on a steady inflow of official assistance, which in the long run might not continue as a consequence of the technological disruptions of the global fossil fuel market.

Consequently, the key policy question is what can be done about the unsustainable current account deficits of MENA economies that remain geo-strategically important for a variety of global and regional actors?

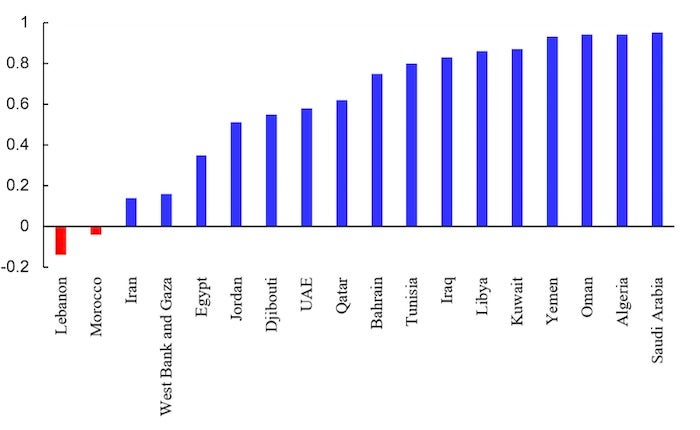

Some analysts, including at the IMF, believe that fiscal austerity is the answer and that it is urgent. But the evidence indicates that the correlation between fiscal deficits and current account deficits during the past twenty years or so has been low or even negative in several MENA economies (see Figure 4).

As fiscal policy has lost some of its traction, implementing structural reforms capable of raising GDP per worker is a more long-lasting way to go. Our report discusses reforms in fiscal expenditures, trade-related policies, social protection and labor markets, and state-owned enterprises in network industries. Current account and trade deficits in key MENA economies cannot persist indefinitely, and the capacity of the GCC to finance them is withering away. The time for structural reforms in MENA has arrived with force.

Join the Conversation