Ooli showing her identity documentation and Multicaixa card. Photo: Helly Dharmesh Mehta/ World Bank

Ooli showing her identity documentation and Multicaixa card. Photo: Helly Dharmesh Mehta/ World Bank

Frail and with a baby hanging in her arms, Ooli seemed to be living all by herself in a little shack built of straw and mud. She is a beneficiary of the Kwenda program, Angola’s flagship social protection program, from the Bata-Bata community within the municipality of Humpata in Huila province. When she received her cash transfers, she judiciously invested in livestock. Her first round of investment was in pigs, but the dry season left them dead shortly. Undeterred, she used part of her second tranche of cash transfer, to buy chicks. The chicks seemed healthy and were roaming around free next to her house. Yet only time will tell whether these chicks can withstand the challenges at the onset of the next dry season.

Dry seasons and droughts have become a consistent and prolonged feature of the ecosystem of Huila and other parts of Southern Angola.

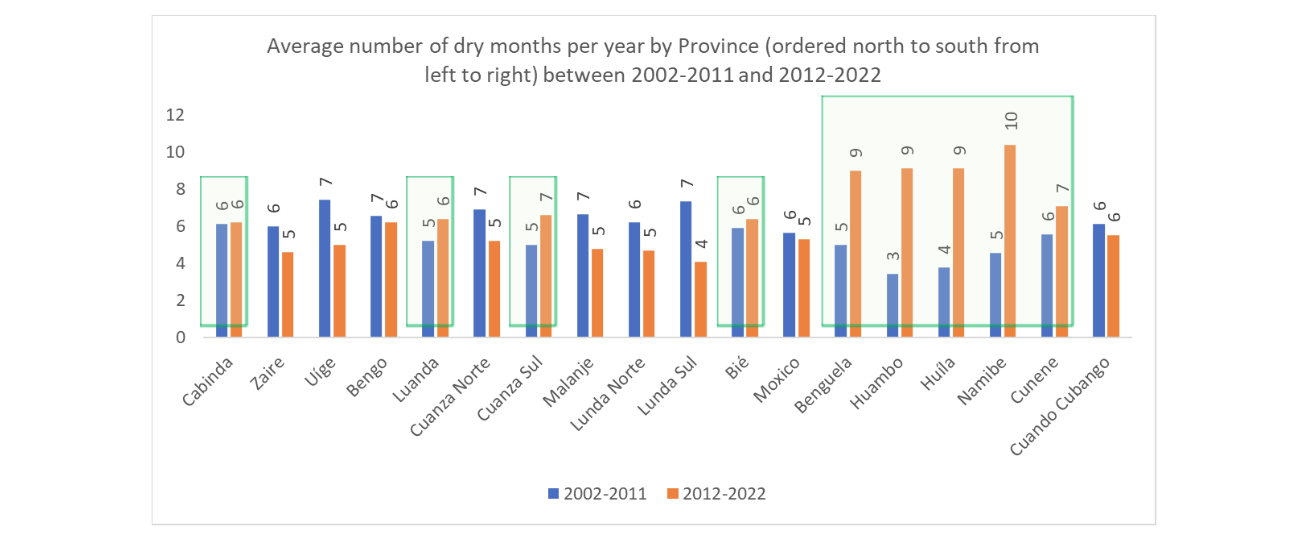

Dry seasons and droughts have become a consistent and prolonged feature of the ecosystem of Huila and other parts of Southern Angola. Recent analysis, in Establishing an Adaptive Social Protection System in Angola (2024), using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI, a proxy for vegetation health from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, MODIS) shows that, on average, the frequency and duration of dry seasons have been increasing quite steeply in Angola, particularly, in the southern region. Dry months are marked by negative NDVI anomalies, defined as the difference between the values observed at a particular point in time in a specific province and the long-term averages in that province. In the provinces of Huila, Huambo, Benguela, and Namibé, between 2002 and 2011, there was on average 3 to 5 dry months annually. However, from 2012 to 2022, this average rose sharply to 9 to 10 dry months per year. This trend is starkly visible at the municipality level too - municipalities experiencing prolonged droughts now endure on average over nine consecutive dry months annually. Additionally, half of all provinces show an increase in the average number of dry months per year between 2002-11 and 2012-22 periods. In these provinces and municipalities, dry seasons and droughts have become the new normal. And with the global temperatures continuing to rise, it is only a matter of time before the other provinces follow suit.

Fig 1. - Average number of months per year with negative NDVI anomalies have increased particularly in the Southern Provinces of Angola

Source: Analysis based on Establishing an Adaptive Social Protection System in Angola (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

This is not just Angola’s story—it reflects a global trend. Since 2000, the frequency and duration of droughts has increased by 29 percent globally. Country-specific analysis undertaken in Brazil and Ethiopia reveal the same pattern. This can erode livelihoods of the poor and diminish their resilience to shocks.

Since 2000, the frequency and duration of droughts has increased by 29 percent globally.

While cash transfers have shown to build resilience among poor households likely to be affected by climate shocks, overlapping constraints faced by households can limit their impact. In Ooli’s village, what stood out was its extreme isolation: the nearest motorable road, water source, and markets were kilometers away. Accessing water required at least a couple of hours on foot, and by the cloudy brown water Ooli showed us, our guess was that it likely came from an open water source. And, while Ooli is among the households receiving cash transfers through a Multicaixa card (one third of a million beneficiary households receive cash transfers this way), the card proved to be quite futile for her until a banking agent arrived with cash. With the remoteness, the lack of access to essential services also meant poor education and health outcomes for her and her children.

Addressing these overlapping constraints requires a layered approach at the household, community, and local economy level. For cash transfers to have a sustainable impact on livelihoods, complementary services and interventions must also be provisioned. At the household level, these include life and business skills trainings, start-up grants, inclusion in savings groups, mentorship and coaching programs—approaches aligned with global evidence. Climate resilience training can further empower households to adopt improved technologies, such as drought-resistant seeds, and recognize early signs of drought to adapt proactively. At the community level, activities could include sensitization on understanding patterns of climate change, and how to protect community resources against its negative impacts. At the local economy level, these problems call for governments to start investing in broader infrastructure and services, such as access to health and education facilities, water, and sanitation. Incorporating such a layered approach to support Ooli could mean substantially improved livelihood and welfare outcomes for her and her family.

To truly build resilience and break the cycle of poverty in a climate-challenged world, cash transfers must be complemented by investments in skills, services, and infrastructure.

To truly build resilience and break the cycle of poverty in a climate-challenged world, cash transfers need to be complemented by investments in skills, services, and infrastructure. A holistic approach that empowers households, strengthens communities, and supports local economies is key to enabling vulnerable populations not just to survive, but to thrive.

Join the Conversation