Stylized image of a mountain landscape with a tree in the forefront in tones of yellow and green with report title "Nature’s Frontiers, Achieving Sustainability, Efficiency, and Prosperity with Natural Capital".

Stylized image of a mountain landscape with a tree in the forefront in tones of yellow and green with report title "Nature’s Frontiers, Achieving Sustainability, Efficiency, and Prosperity with Natural Capital".

There’s a widespread belief that economic growth is killing our planet. There’s plenty of research over decades that supports this. Fifty years ago, the Club of Rome published its famous report, The Limits of Growth, which argued that without big changes in consumption patterns, environmental degradation and natural resource depletion would lead to a catastrophic decline in populations and living standards.

Since the report, the global population has more than doubled to 8 billion today, and incomes—and thus, consumption—rose around the world. An unfortunate byproduct of this growth has been a decline in almost every environmental indicator.

Since the year 2000 alone, the world has lost more than 10% of global tree cover, an area roughly half of the size of the United States. Water quality is declining in countries rich and poor alike, threatening growth and harming public health. Air pollution now cuts the average person’s life short by 2.2 years, claiming more lives each year than all wars and forms of violence. And 40% of all land is now considered degraded, making the climate crisis worse, reducing biodiversity, and threatening food security.

With these vital forms of natural capital all in decline, a critical question must be asked: Can we do better? Can we use our natural capital in more efficient ways and at the same time allow people to lead better lives while protecting our planet from destruction?

"Can we use our natural capital in more efficient ways and at the same time allow people to lead better lives while protecting our planet from destruction?"

Almost all countries inefficiently exploit natural capital

To answer this question, the World Bank teamed up with the Natural Capital Project, a team of scientists, economists, software engineers, and real-world professionals. This partnership fostered the development of agricultural, ecological, and economic models that can guide us to make the best possible use of land, water, and air. These models draw on big data—over 8 billion data points—on forests and vegetation, agricultural production, water resources, climate, and air pollution. The results are detailed in a new report, Nature’s Frontiers: Achieving Sustainability, Efficiency, and Prosperity with Natural Capital.

The findings of this modeling suggest that almost all countries around the world are inefficiently exploiting their natural capital. They grow crops in climates and geographic conditions unsuitable for those crops, raise livestock on lands better suited for agriculture, and deforest vast swathes without replanting—limiting future forestry revenues and destroying critical carbon sinks and natural habitats. These actions are causing large efficiency gaps.

This misallocation of natural capital can be attributed to numerous factors, including ill-advised subsidies, insecure property rights, and lack of enforcement of protected areas. However, the primary reason is that natural capital is often unpriced or underpriced, distorting incentives. This absence of pricing results in natural capital being wasted, used unsustainably, and rarely allocated to maximize the benefits it could provide.

Closing efficiency gaps could help tackle our most pressing challenges

Yet, there is promising news. Correcting these inefficiencies and closing the efficiency gaps could help tackle some of the world's most pressing challenges. Almost every one of the 146 countries we studied has significant efficiency gaps. They could all benefit from utilizing their natural capital more efficiently. When we consolidate the data from all these countries, the results are staggering.

"Almost every one of the 146 countries we studied has significant efficiency gaps. They could all benefit from utilizing their natural capital more efficiently. "

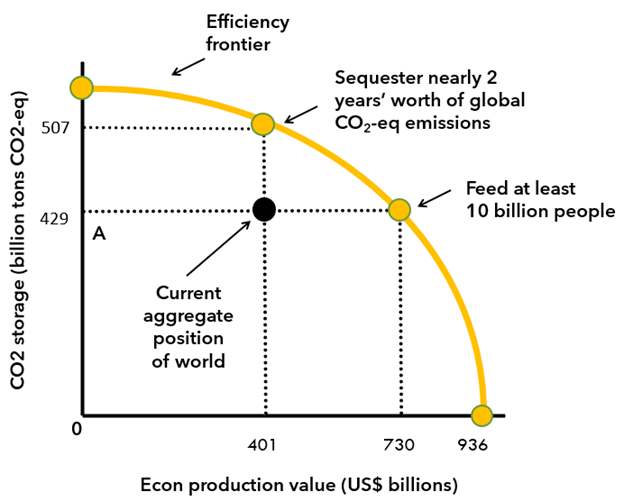

We found that countries can close natural capital efficiency gaps through different land use and land cover combinations. The figure below depicts an “efficiency frontier” of optimum levels of economic production and carbon sequestration and shows where we stand today. Currently, the world nets about $401 billion a year from its land. If all countries were to close their efficiency gaps in production while maintaining the current level of carbon storage, they could nearly double that number to $730 billion a year and reach the efficiency frontier. This could be accomplished without environmental impacts, such as the release of carbon, or methane, or the loss of biodiversity. Perhaps more impressive, if we consider this in terms of calories produced from agriculture, rather than dollars, this would amount to more than enough calories needed to feed the world out to 2050, when the UN projects the global population will hit 10 billion people.

Likewise, if all countries were to close efficiency gaps by maintaining production but sequestering more carbon, they would reach the frontier and the world could sequester an additional 78 billion tonnes of carbon in its landscapes. This is equivalent to nearly 2 years’ worth of global emissions and would give the world much needed time to decarbonize. And again, this could be accomplished without reducing economic growth or food production. The gains come simply by closing efficiency gaps and using our natural capital to its fullest potential.

Achieving these ambitious goals will not be easy. We lack a magic wand to instantly make our landscapes more efficient. We need to mobilize governments, businesses, and individuals to initiate these changes, which can only be achieved by implementing the appropriate policies and incentives. What these policies will look like depends on the country and its circumstances. The next phase of this project is to collaborate with World Bank country teams and clients to bring these goals to fruition, and we will need your support to achieve this.

Download the report: Nature’s Frontiers: Achieving Sustainability, Efficiency, and Prosperity with Natural Capital

Join the Conversation