Authors defend that dealing with climate change will require both mitigation of emissions and adaptation to the consequences. Photo: Curt Carnemark / World Bank

Authors defend that dealing with climate change will require both mitigation of emissions and adaptation to the consequences. Photo: Curt Carnemark / World Bank

Development is, at its core, the process of making investments now that increase the future growth of a country. There are few investments one can make that have as high a payoff as investing in human capital and education. In some low and middle-income countries (LMICs) the long-term return on investing in human capital is more than 10x that of investing in physical capital (Collin Weil 2018). Other work has found that differences in schooling and learning can account for “between a fifth and a half of cross-country income differences (Angrist et al., 2019).

But like physical capital, investments in human capital will be affected by climate change, and like every sector of the economy, the education sector will need to adjust to the realities of a warmer and more unstable climate. How the education sector can most effectively engage with the challenges posed by climate change remains an open question.

Dealing with climate change will require both mitigation of emissions (“mitigation”) and adaptation to the consequences of a changed climate (“adaptation”). Although all sectors of the economy will need to substantially reduce their carbon emissions to facilitate a transition to a low-emissions world, currently the education sector contributes relatively little to global emissions.

Broad-scale statistics are hard to come by but in higher-income countries it appears that the contribution of the education sector to emissions is on the order of 2-3% of a countries emissions, with most of these coming from purchased electricity. Estimates from the United States suggest that U.S. institutes of higher education account for less than 2% of emissions, with Scope 2 and 3 emissions accounting for 70% of these emissions (Sinha et al 2010). Similarly, in South Africa, total energy consumption by all schools in accounts for less than 2% of total energy consumption. This is in contrast to the industrial and agricultural sectors, which in the U.S. contribute 24% and 11% respectively, of greenhouse gas emissions.

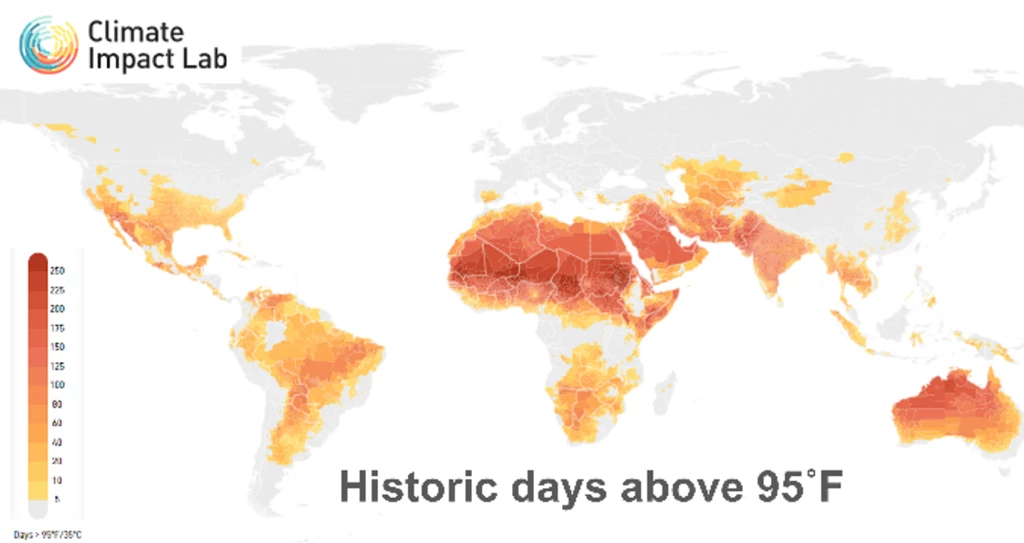

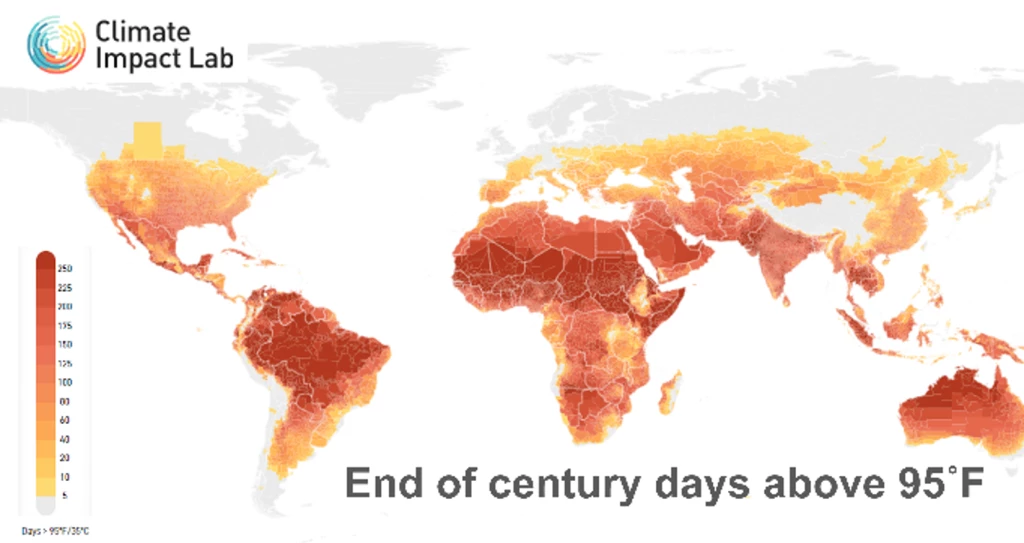

By contrast, the education sector can potentially play a large role in adaptation. A robust and rapidly growing scholarly literature is documenting the negative consequences of climate change, and of high temperatures in particular, for students. This link is important because projections show that large parts of the world will be exposed to substantially higher temperatures in a warmer world.

|

|

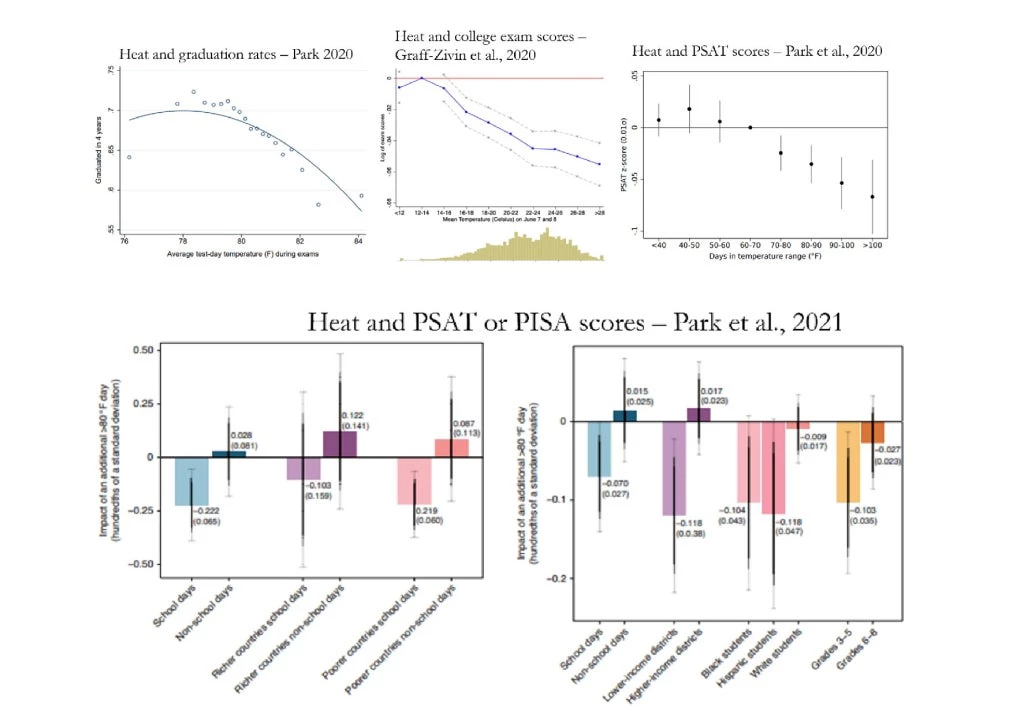

Recent work reveals that students perform substantially worse on exams when they take them on hotter days. This effect is true of high-stakes exams that determine whether students can graduate from high school (Park 2020) and of lower-stakes exams without such long-term consequences (Zhang et al 2022). In New York City, taking an exam on a day 90⁰F (32⁰C) or hotter reduced performance by 13% of a standard deviation. Increasing the temperature on the day of the exam by roughly 5⁰F (2.7⁰C) reduces the likelihood of graduation by almost 5%. In China, data from 14 million high-stakes college entrance exams suggest that students who take the exam on a day with temperatures over 82.5⁰F (28⁰C) have scores that are 6% lower compared to students who take it under optimal temperature conditions (Graff Zivin et al 2020).

These effects are not limited to the short term either. Looking at 10 million test scores taken by students over 13 years, Jisung Park and co-authors find that the same student performs worse on an exam when taking that exam following a year with more days over 90⁰F (32⁰C) than average, controlling for the temperature on the day the exam itself was taken (Park et al., 2020). The same result holds looking at data from 67 countries on scores of 15-year-olds on the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) exam, when the exam is taken following hotter-than-average years, students perform worse, suggesting they learn less during the intervening years (Park Behrer Goodman, 2021). These impacts are largest in low-income countries, for poor students, and for minority students, presumably driven by less access to effective adaptations. As a result, increases in extreme temperature stand to exacerbate existing inequalities in the education sector. In on-going work we – along with Kibrom Tafere – are expanding this work to examine outcomes in Ethiopia, Chile, and Mexico.

Temperature also has indirect effects, causing families in agricultural communities to pull students out of school in years with larger crop losses from high temperatures in ways that negatively impact their human capital formation (Garg et al, 2020). High temperature also increases absenteeism and disciplinary problems, but only in settings without air conditioning.

Addressing the negative consequences of heat exposure on human capital formation by encouraging investments in adaptation may be more consequential than reducing emissions from schools directly. To see why, consider the following example. Imagine a reasonably large high school in the southeastern United States installs solar panels on the roof of the school, reducing its electricity-related greenhouse gas emissions by half. Based on typical school electricity consumption, the carbon intensity of electricity in the southeast, and the U.S. government’s social cost of carbon ($50), the present value of the global benefits of the avoided tons of CO2 emitted over the next ten years is likely on the order of $1.5 million USD. If, instead of installing solar panels, the school had invested in installing air conditioning in all its classrooms (which may have a different set of costs than installing solar), the results from the papers above suggest that the present value of the increased future earnings of its students would have been approximately $2.6 million dollars.

That is not to say the adaptation front is the only one on which the education sector should engage with climate change. Schools may in any case benefit from reducing their energy costs—for example, the savings can be put towards paying teachers more. Other energy efficiency investments in school buildings—like upgraded windows and insulation or high-efficiency heat pumps—can also improve climate control. And the education sector can potentially play a role in changing opinions about climate change. However, research on how effectively education alone can achieve societal change is mixed. Work from the United States suggests that a 1-year intensive course led to reductions in self-reported personal emissions of 10%, a large portion of which came from choosing to buy a different car. Recent work in Chile indicates that environmental education programs did not succeed in changing the opinions or behavior of students’ parents (Jaime et al., 2022).

Still, adapting educational institutions to the impacts of climate change strengthens one of the other ways that education can help combat climate change. Research suggests that those with higher levels of education have higher adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change, and so suffer fewer damages from the consequences of climate change (O’Neill et al 2020). Advancing adaptation to climate change in the education sector makes it easier for to achieve its goals of better learning outcomes, which is itself a means of combatting climate change.

Education is a powerful engine of growth that is threatened by climate change. Discovering ways to adapt schools and modes of educating students to reduce the negative consequences of exposure to climate extremes is a critical role of education research and policy. Considering the substantial, compounding effects of improving students’ ability to learn and accumulate human capital early in life, discovering and promoting climate adaptations for young learners may be the most consequential way for the education sector to engage with the challenges posed by climate change.

Join the Conversation