Credit: Elle Aon / Shutterstock.com

Credit: Elle Aon / Shutterstock.com

Reform committees (also known as reform councils) are institutional mechanisms or structures tasked to hold policy discussions, make specific recommendations on regulatory issues, monitor improvement efforts, and ensure regulatory coherence between agencies, while guaranteeing regulatory quality. Earlier this year we wrote about a new project on business reform committees, which studies these institutional bodies that focus on business regulatory reforms and ensure successful reform implementation. We are gathering these data because appropriate institutional arrangements have been recognized as an important component of a comprehensive strategy for regulatory reform. The ultimate objective is to provide data to better understand which roles and attributes of these bodies matter for development. In this blog we share three preliminary findings:

Finding #1: Globally, the vast majority of economies have a business regulatory reform body, although there are large cross-country differences

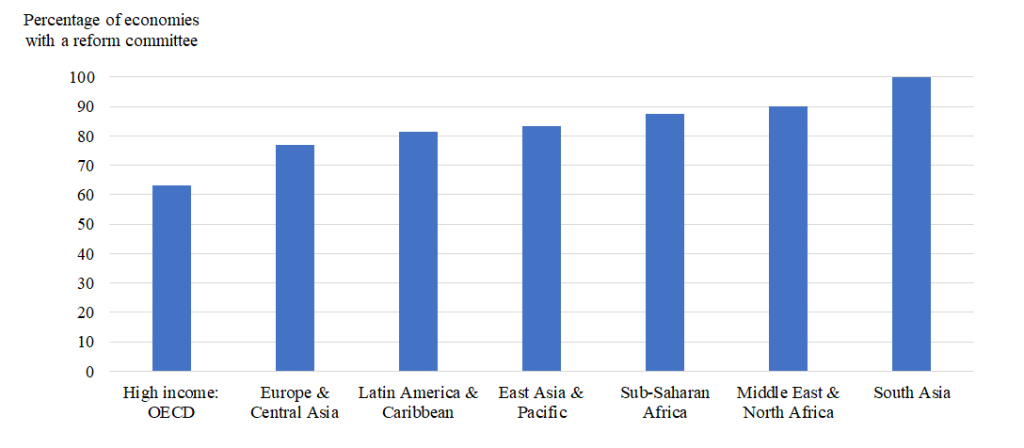

Our analysis of 100 economies shows that 80 percent have a functioning reform committee, defined as an active public, private, or public-private entity responsible for implementing reforms in business regulations, with a mandate to improve the business environment and the country’s competitiveness (figure 1). Our findings suggest that reform committees exist across all regions and income groupings. While an official governmental decree or cabinet decision defines the committee’s mandate in most economies, their structure, level of autonomy, scope, and other attributes can be very different.

Reform committees across the OECD high-income countries have been well studied, such as the case of the Republic of Korea, whose Regulatory Reform Committee has been in place since 1998. Established directly under the authority of the president, the committee has a strong oversight component to develop and coordinate regulatory policy, and review and approve regulations.

Our data provide new insights into reform committees that have been established recently, such as, Ecuador’s Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship Committee, which was established in 2019 to promote and strengthen competitiveness by monitoring and implementing the coordination of public policy for the economic development.

Figure 1: Business regulatory reform committees across regions

Source: DECIG Reform Committees Data

Note: The analysis consists of 100 economies: East Asia & Pacific (12), Europe & Central Asia (13), High income OECD (19), Latin America & Caribbean (16), Middle East & North Africa (10), South Asia (6), Sub-Saharan Africa (24).

Finding #2: For almost half of the reform committees, the priorities are set directly by the president’s and/or prime minister’s office

The level of political support can contribute to the overall success of regulatory reforms. Leadership at the presidential or prime ministerial level allows reform committees to successfully coordinate actions across government departments, overriding typical bureaucratic barriers that often prohibit inter-ministerial coordination. Such approach is taken across close to half of the reform committees globally. For example, in Colombia the National Commission for Competitiveness and Innovation (Sistema Nacional de Competitividad e Innovación) is led by the president and composed of regional governors as well as business and academia representatives. Similarly, in Senegal, the Presidential Investment Council (Conseil Présidentiel de l'Investissement) is housed in and led by the president’s office.

Other countries have chosen a different – rather decentralized - structure. A more decentralized system doesn’t imply a lack of coordination, but could be as a result of the decentralized model of government administration. For example, Spain’s Committee for Better Regulations is an inter-administrative cooperation committee whose secretariat sits within the Directorate General of Economic Policy, housed in the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation. In Jamaica, the Secretariat of the National Competitiveness Council (NCC) created in 2010, is housed at the investment promotion authority, Jamaica Promotions Corporation (JAMPRO). Under supervision of the Ministry of Industry, Investment & Commerce and JAMPRO, NCC facilitates and monitors business reforms and serves as a platform for public-private dialogue to promote business environment.

In Mongolia, the committee is independent from the government. The Business Council of Mongolia (BCM) is a membership-based association of 260 businesses, NGOs and international organizations (including the World Bank). Private sector representatives work voluntarily in six working groups that provide suggestions to the government in the areas of finance, competition, energy and infrastructure, environment innovation and taxation. A private representative elected by the council oversees the council.

Finding #3: The private sector is represented at the steering board or in working groups of the reform committee in two-thirds of the economies; however, representation does not equal engagement

An early and active involvement of private sector representatives helps public officials better understand bottlenecks affecting the productivity of a sector. Thanks to their knowledge of existing sector-specific bottlenecks and practical challenges, private sector representatives can provide critical insights into the existing regulatory issues and thereby inform evidence-based structural reforms.

Our data show that in two-thirds of the economies, the private sector is represented at the level of the steering board or working group of the reform committee. However, its role and level of engagement can be very different. For example, PEMUDAH, Malaysia’s reform committee, is co-chaired by representatives from both the public and the private sector and comprises 10 private sector representatives. Its institutional structure facilitates an active role of the private sector and makes these representatives equal players in the business regulation reform agenda. Empowering the private sector with adequate agenda-setting and decision-making powers enhances their incentive to participate.

In Mexico, the private sector participates in the National Council for Regulatory Improvement through the Regulatory Reform Observatory composed of members from the civil society and businesses. One of the functions of the Regulatory Reform Observatory is to suggest improvements to the regulatory policy to the National Council, as well as to propose indicators or methodologies to implement, measure and follow up on reforms.

In some economies, reform committees have little engagement with the private sector. For example, the State Regulatory Service of Ukraine, a structure created in 2014 to improve business environment specifically for domestic companies, has no established working groups and private sector participation is limited to workshops where legislative changes are announced.

A successful private and public sector collaboration early in the process of formulating business regulatory proposals is important for an economy’s overall development and can be credited with improving investment climate conditions, sustained economic growth, good governance, and innovation.

Going forward, in the second year of the project, our team will continue to collect data on specific attributes of reform committees, including whether these structures have a temporary or permanent mandate. The project will also dive deeper into the roles and obligations of the private sector as stakeholders in the regulatory system. The ultimate objective remains the same – provide data and knowledge to help governments strengthen their institutions for better business regulations.

Join the Conversation