Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine / Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine / Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

As many of us are returning to “normal” life following what will hopefully be the worst of this pandemic, governments in low-income countries (LICs) are still grappling with how to dramatically boost COVID-19 vaccination rates. As of the end of July 2022, only around 1 in 4 people in LICs had received a COVID-19 vaccine, and only one percent of the population had received a booster. While this is driven by a range of factors, such as supply shortages, limited demand for COVID-19 vaccines is also a major challenge. To date, relatively little attention has been given to the extent to which people’s willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine is influenced by the attitudes of other members of their household .

We examine this issue in a new study that draws on a unique, nationally representative, in-person survey and a novel online randomized survey experiment. These surveys took place in Zambia, which has similar levels of COVID-19 vaccination rates to many other Sub-Saharan African countries. The in-person survey involved asking all the members (aged ten years and above) of over 10,000 households whether they would be willing to get vaccinated, and the online experiment tested how accurate information about the benefits of getting a COVID-19 vaccine boosted willingness to get vaccinated.

Key insights from the study:

-

The strongest predictor of people’s willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine is whether other household members were also willing

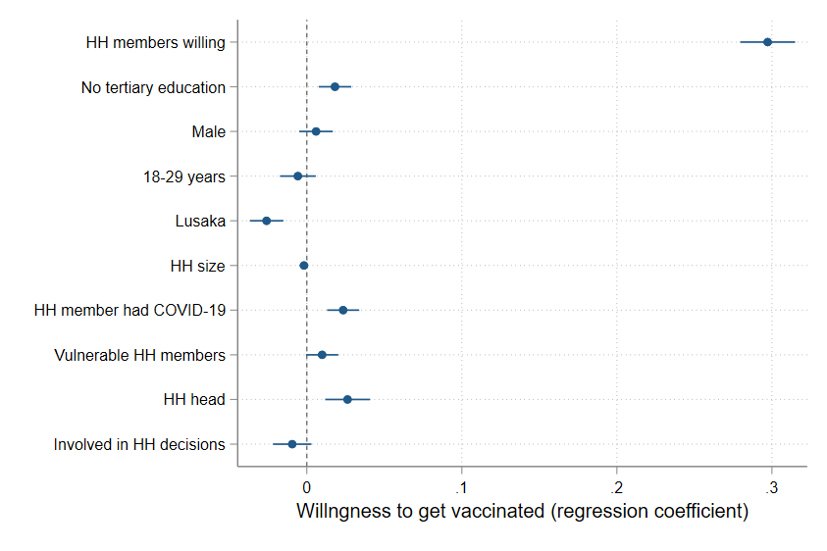

The in-person survey revealed that over 60 percent of household members were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine when the household head was, while less than 15 percent were willing when the household head was not . People’s willingness to get vaccinated was also strongly correlated with not only the household head’s attitudes but also whether other household members were willing. The figure below shows that after controlling for the background characteristics of respondents, the likelihood an individual would state they were willing to get vaccinated was around 30 percentage points higher when other household members were also willing to get vaccinated. No other characteristics had such a strong correlation with people’s willingness to get vaccinated.

This result suggests that in many instances, it would seem appropriate to consider the attitudes towards vaccines of household members as a collective unit instead of a group of individuals. Similar points have been made about other topics, such as political preferences, whereby the correlation of attitudes within households tends to be extremely high. From a policy perspective, this suggests that targeting outreach campaigns at the household level may be a very effective way to boost vaccination rates.

-

Information about the benefits of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine leads to greater willingness to get vaccinated, particularly for people in households where other members were unwilling

The online experiment showed that communicating the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines can markedly increase people’s willingness to get vaccinated . Respondents were randomly assigned to either a treatment group (received a message about the benefits of being vaccinated) or a control group (did not receive a message). The figure below shows respondents who received the treatment were more willing to get vaccinated, particularly if they were in households where other members were unwilling. A similar pattern holds regarding the impact of the treatment on reducing people’s unwillingness to get vaccinated. Interestingly, there were no notable differences between respondents in households based on whether the household head was willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine.

-

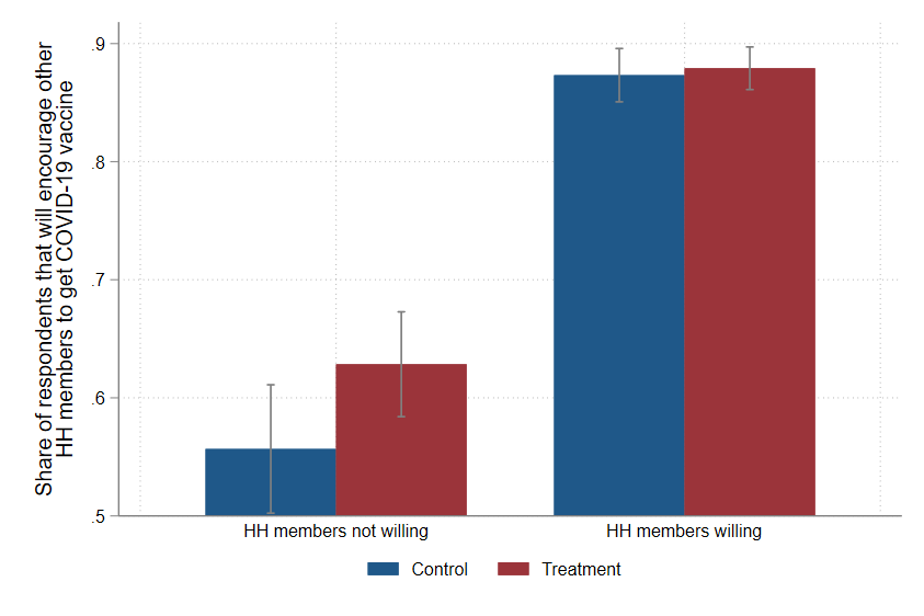

People who receive information about the benefits of getting vaccinated are also more likely to encourage other household members to get vaccinated

The online experiment showed that communicating the benefits of COVID-19 did not only lead to increased willingness for respondents to get vaccinated but also led to people being more likely to encourage other household members to get vaccinated . The figure below shows this treatment effect was exclusively driven by respondents in households where other members were unwilling to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. In other words, respondents in previously “reluctant” households were more likely to respond positively to the treatment than those in households who reported acquiescence to COVID-19 vaccination.

These results show a second-round effect from the treatment (whereby respondents were more likely to encourage others in their household to get vaccinated). As such, communicating accurate information may create a virtuous cycle whereby both recipients of the information and others in their household become more willing to get vaccinated.

Collectively, the insights from the study suggest that there would be considerable value in policy makers taking a multi-pronged approach (i.e., at both the individual and household level) to vaccine outreach. If one person in a household is provided timely and relevant information to ease their concerns about vaccination, they may be able to encourage their household members to get vaccinated. If a household is approached together, any concerns can be addressed in one interaction with the family unit.

Join the Conversation