Identifying and making policies that effectively counter the drag of aging on global growth is imperative for the long haul. During the last 15 years, close to 80 percent of global growth took place in middle- and high-income countries that, during the next few decades, will undergo rapid aging, with shrinking population shares in working age and growing shares of elderly.

Apart from slowing down global growth, these developments will make it more difficult to achieve the World Bank’s objectives of eradicating extreme poverty and enhancing shared prosperity. This is an insight of our Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016 – Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change, launched last year jointly with the IMF. Echoing this message, a recent Policy Research Note, “ Slowdown in Emerging Markets: Rough Patch or Prolonged Weakness?,” singles out declining rates of working-age population growth in emerging markets (EMs) as a source of the recent growth slowdown for this group of countries, which accounted for more than 60 percent of global growth 2010-2015.

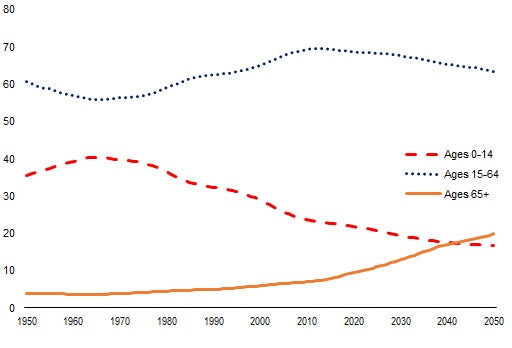

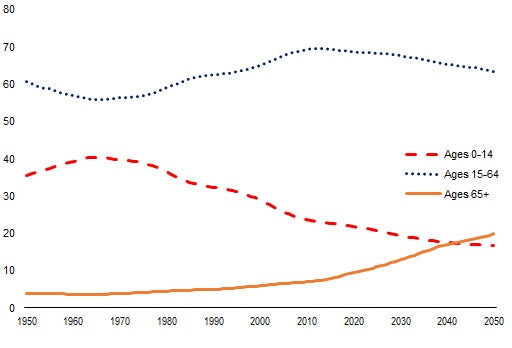

At a recent Brookings – Australian National University workshop on drivers of the global economy towards 2020 and beyond, a presentation on the BRICs shows that these demographic trends also apply to this critical subset of the EMs and will continue in coming decades – see Figure.

BRICs: Population shares by age group, 1950-2050 (%)

So what policies may effectively counter the negative effects of aging on growth and prosperity?

The strongest positive effects on growth and welfare may come from efforts to maximize the share of the working population. Efforts to raise fertility and increased immigration may certainly help. However, their positive effects will only be felt with a long lag (for the case of fertility increases) and may not be politically feasible at levels that make a difference (in the case of immigration).

The share at work may be boosted by delaying the participation declines that set in as people age. In many countries, it may also be possible to raise labor force participation in younger age groups, especially among women. (Of course, one should be careful to make sure that education is not sacrificed.) Higher labor force participation may be brought about via a package of measures including (a) pensions systems that automatically adjust minimum retirement ages upwards as life expectancy increases and reward delayed retirement; and (b) public support for child care and flexible work arrangements that make it easier for both parents to work while bringing up their children.

In support of a highly productive labor force in a world with rapid technological change, incentives are needed to make learning a life-long process, ensuring that older workers, who can draw on long experience, don’t fall behind. Financial sector policies are needed to support the high savings rates that enable households to contribute to financial security as they age and finance investments in physical capital that contribute to high labor productivity.

To make sure that shared prosperity encompasses all, special efforts will be needed to attend to the needs of the growing numbers of elderly, including a social safety net that catches those with insufficient incomes and systems for health services and long-term care. Together, such policies can bring about stronger growth and prosperity, not only in the aging countries but also globally thanks to flows of trade, workers, remittances and capital.

Do currently aging countries offer lessons for low- and middle-income countries that are in a less advanced demographic stage? Yes.

The main lesson is that, in the long run, policies that today seem unimportant (since the elderly represent a small population share and the fiscal costs are small) in fact, in the long run, turn out to have major consequences for living standards and government spending. Policies that are put in place at earlier demographic stages influence people’s expectations and create institutions with clout in the political economy. As a result, it is often very difficult to change policies and systems even as they become increasingly ill-advised and unsustainable. Also when it comes to aging, it pays off to think ahead, both for individuals and countries.

Apart from slowing down global growth, these developments will make it more difficult to achieve the World Bank’s objectives of eradicating extreme poverty and enhancing shared prosperity. This is an insight of our Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016 – Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change, launched last year jointly with the IMF. Echoing this message, a recent Policy Research Note, “ Slowdown in Emerging Markets: Rough Patch or Prolonged Weakness?,” singles out declining rates of working-age population growth in emerging markets (EMs) as a source of the recent growth slowdown for this group of countries, which accounted for more than 60 percent of global growth 2010-2015.

At a recent Brookings – Australian National University workshop on drivers of the global economy towards 2020 and beyond, a presentation on the BRICs shows that these demographic trends also apply to this critical subset of the EMs and will continue in coming decades – see Figure.

BRICs: Population shares by age group, 1950-2050 (%)

So what policies may effectively counter the negative effects of aging on growth and prosperity?

The strongest positive effects on growth and welfare may come from efforts to maximize the share of the working population. Efforts to raise fertility and increased immigration may certainly help. However, their positive effects will only be felt with a long lag (for the case of fertility increases) and may not be politically feasible at levels that make a difference (in the case of immigration).

The share at work may be boosted by delaying the participation declines that set in as people age. In many countries, it may also be possible to raise labor force participation in younger age groups, especially among women. (Of course, one should be careful to make sure that education is not sacrificed.) Higher labor force participation may be brought about via a package of measures including (a) pensions systems that automatically adjust minimum retirement ages upwards as life expectancy increases and reward delayed retirement; and (b) public support for child care and flexible work arrangements that make it easier for both parents to work while bringing up their children.

In support of a highly productive labor force in a world with rapid technological change, incentives are needed to make learning a life-long process, ensuring that older workers, who can draw on long experience, don’t fall behind. Financial sector policies are needed to support the high savings rates that enable households to contribute to financial security as they age and finance investments in physical capital that contribute to high labor productivity.

To make sure that shared prosperity encompasses all, special efforts will be needed to attend to the needs of the growing numbers of elderly, including a social safety net that catches those with insufficient incomes and systems for health services and long-term care. Together, such policies can bring about stronger growth and prosperity, not only in the aging countries but also globally thanks to flows of trade, workers, remittances and capital.

Do currently aging countries offer lessons for low- and middle-income countries that are in a less advanced demographic stage? Yes.

The main lesson is that, in the long run, policies that today seem unimportant (since the elderly represent a small population share and the fiscal costs are small) in fact, in the long run, turn out to have major consequences for living standards and government spending. Policies that are put in place at earlier demographic stages influence people’s expectations and create institutions with clout in the political economy. As a result, it is often very difficult to change policies and systems even as they become increasingly ill-advised and unsustainable. Also when it comes to aging, it pays off to think ahead, both for individuals and countries.

Join the Conversation