The COVID-19 pandemic created one of the most severe global health crises in modern history, significantly affecting the provision of health care assistance. As quarantine restrictions did not allow patients to visit their doctors in person, some countries switched to e-health services, following a digital health path set by the World Health Organization even before the pandemic.

However, e-health applications require a well-developed digital infrastructure, advanced technological tools, and relevant digital skills by doctors and patients. For that reason, many developing countries have difficulty leveraging this opportunity.

The term “e-health” entails a broad spectrum of applications. From telemedicine — which consists of online consultation between a doctor and a patient — to remote surgery, the inputs required in connectivity, skills, and logistics vary significantly. Telemedicine is vital to deliver essential health services in rural areas, which often face a shortage of skilled health workers. Consultation with more sophisticated facilities and professionals would help provide such services to remote communities. Moreover, a connected health system makes it possible to create a shared patient and drug database and, in general, permits better communication between different actors. In this regard, it is essential to rely on a solid data infrastructure that includes data centers and cloud services.

As part of the Digital Economy for Latin America (DE4LAC) initiative — which maps the current strengths and weaknesses of the national digital economy ecosystem and identifies both opportunities and challenges for future growth — the World Bank has analyzed El Salvador’s telecommunication network to understand to what extent the national health care system could leverage the existing digital infrastructure and develop e-health applications. Our approach consisted in checking the availability of high-speed broadband to health care facilities. To do so, we examined 810,000 internet Speedtest® by Ookla® measurements taken between 2019 and 2020, which were taken within a 400-meter radius of 738 health care facilities (378 in rural and 360 in urban areas). Then, we calculated the average value of the ten nearest speed tests for each facility, assuming that a building has access to a similar level of connection quality recorded in its proximity.

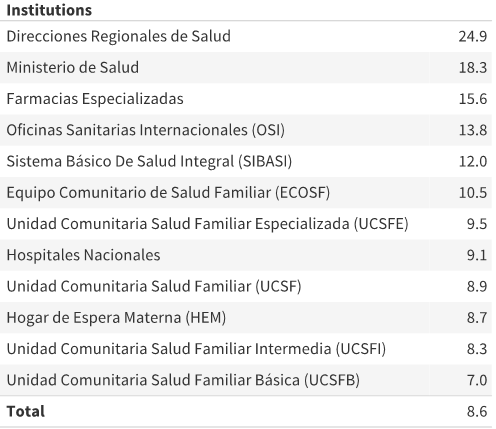

The facilities reporting the highest average internet speed were the Ministry of Health and its regional offices (25 megabits per second (Mbps) and 18 Mbps respectively), pharmacies — 16 Mbps, and international health offices — 14 Mbps. Only about 22 percent of health care facilities had internet speed above 10 Mbps. Fifty-three percent of them recorded an average internet speed below 10 Mbps. One-quarter of the facilities had less than ten tests in their proximity and were taken out of the analysis to mitigate potential distortions.

Overall, 89 sites (mainly primary care facilities) do not have any internet speed test recorded within the 400-meter radius, suggesting a lack of access to the internet.

Table 1: Average 10 Speedtest download speed recorded near health care facilities, Mbps

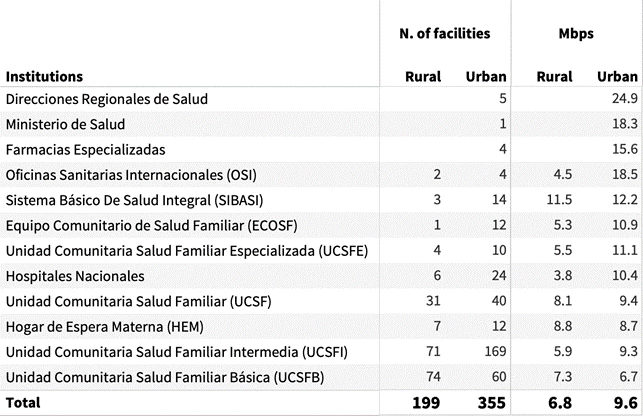

Our findings show a stark disparity in internet quality between health care facilities in urban and rural areas. Only two facilities in rural areas reported an average speed above 10 Mbps; the rest are below this threshold or did not record any access in their proximity. If we look at the split within the same health care facility category, the results are consistent with this finding. For instance international health office (OSI) facilities in urban areas can have, on average, 18 Mbps internet, while their rural facilities only have 4 Mbps.

Table 2: Gap between urban and rural institutions, download speed (Mbps)

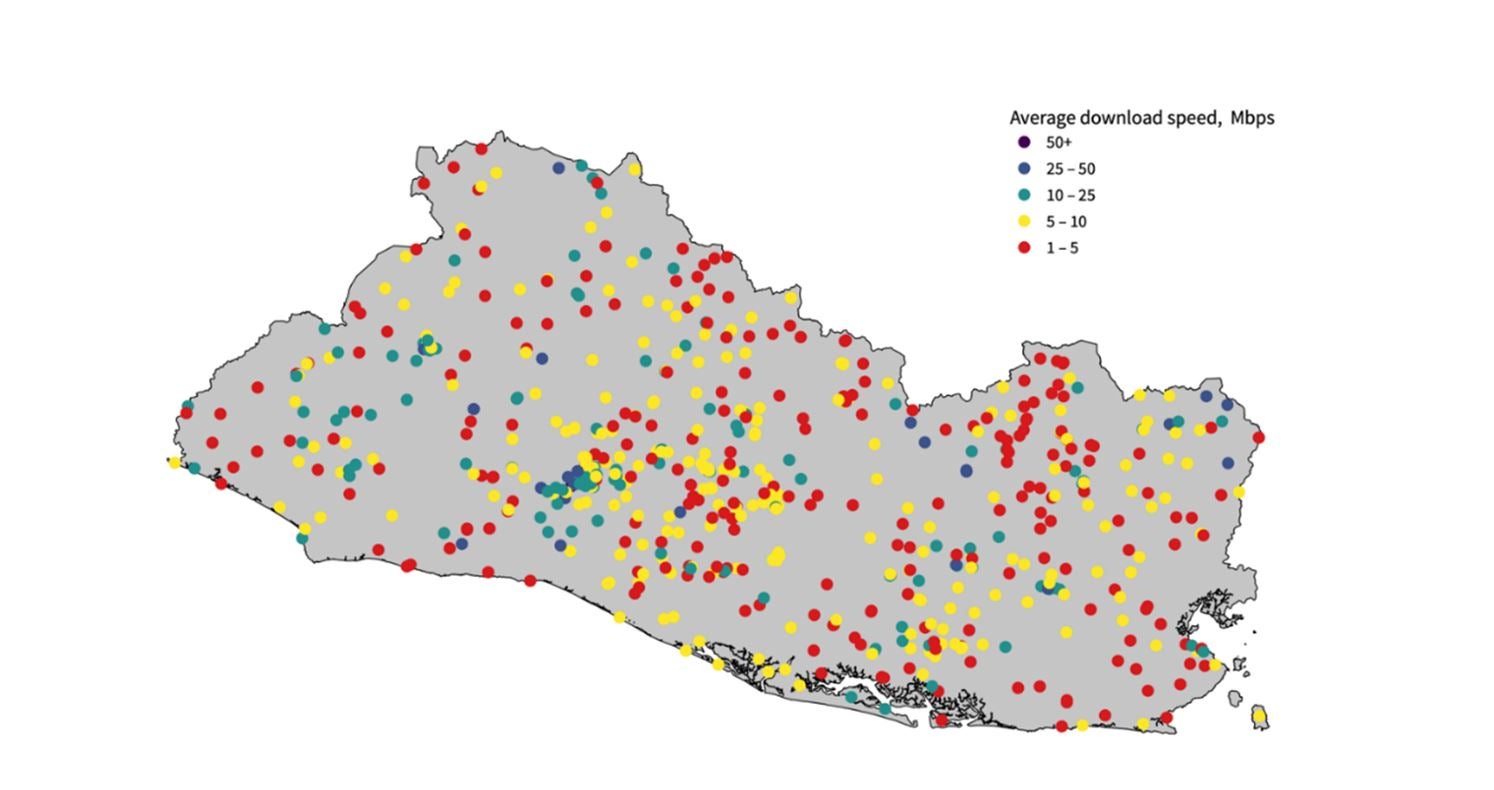

Figure 3: Map of health care facilities’ internet speeds in El Salvador

This analysis suggests that El Salvador should keep working towards deploying a more extended, reliable, and affordable data infrastructure to deliver comprehensive and inclusive e-health services. In most areas of the country, health care facilities seem to have access to a very low-speed internet, significantly limiting the number of digital applications that could be provided. The connectivity challenges also affect some potential patients as almost half of Salvadorans are not online. Good connectivity is particularly challenging in rural areas, which would benefit the most from basic e-health applications.

The public and private sectors can work together to improve the local digital infrastructure, ensuring that health providers and patients have access to an affordable, reliable, and fast internet connection. At the same time, the Ministry of Health has the opportunity to establish digital skills programs and targeted training for health workers to leverage the opportunities offered by e-health applications.

Related:

Digital Development at the World Bank

Digital Development Partnership

Join the Conversation