The Joint Learning Network provides space for countries to discuss best practice approaches for providing essential health services to their people. Photo: Nugroho Sunjoyo/World Bank

The Joint Learning Network provides space for countries to discuss best practice approaches for providing essential health services to their people. Photo: Nugroho Sunjoyo/World Bank

Collaboration encourages problem-solving and shared learning. This philosophy underpins the Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage (JLN), a cohort of health practitioners and policymakers from 36 countries who get together regularly to share “what’s working and what isn’t” in their respective health systems. With ongoing support from the Government of Japan, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Australian Government, the JLN has been successfully co-developing solutions to a broad range of pressing health issues since 2009.

Recently, through its Domestic Resource Mobilization Collaborative (DRM Collaborative), the JLN has been looking at how countries in the Asia Pacific region can work smarter to finance their health systems using their own domestic resources. The topic raises tricky questions for those who have, in the past, been supported by funding from external sources. What’s the best way to navigate a health financing transition that does not lead to increased out-of-pocket (OOP) spending by patients? How can domestic resources be mobilized through general taxation, and augmented by health taxes and social health insurance contributions?

Political will is critical

Increasing publicly funded health expenditure requires political will. As a country’s average income grows, health officials need to actively lobby for an increase in health’s share of total government expenditure. Vietnam illustrates this reprioritization well. Faced with a low share of public spending on health, the National Assembly passed Resolution No. 18/2008/NQ-QH12 (Article 2) “…to increase the share of annual state budget allocations for health, and to ensure that the growth rate of spending on health is greater than the growth rate of overall spending through the state budget.” Following implementation, the annual growth in government health budgetary allocations since 2009 has generally exceeded the average growth of the total government budget.

Speak the language

There is a growing realization that speaking the language of finance decision makers is important. Health-specific arguments do not resonate with finance officials as well as arguments framed around economic concepts such as growth and productivity. The DRM Collaborative’s knowledge product, `A Messaging Guide for Domestic Resource Mobilization,’ was developed to address this need. Drawing on the guide’s messaging, a role-reversal play simulating a meeting between officials from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finance has been run as part of DRM Collaborative meetings. Participants regularly note the strength of evidence-based arguments delivered in language that finance policymakers can relate to – “investing in health improves human capital” or “healthier populations strengthen labor markets, especially for women.”

Allocate money strategically

More money doesn’t always lead to impactful health spending. Efficiency is critical. For example, a country may spend more on drugs, but if it has not negotiated the drug price with population health objectives in mind, increased spending will not improve health. Such inefficiencies raise the question of whether the health sector can effectively absorb additional resources. Conversely, as the DRM Collaborative’s recent report `Old Scars, New Wounds? Public Financing for Health in Times of COVID-19’ prescribes, when fiscal space is limited, targeting the poor with health services to improve health outcomes is a more efficient way of utilizing the health budget. Strategic allocation can provide “more money for health” by improving the efficiency and equity of public health spending (“more health for money”).

Strengthen health taxes

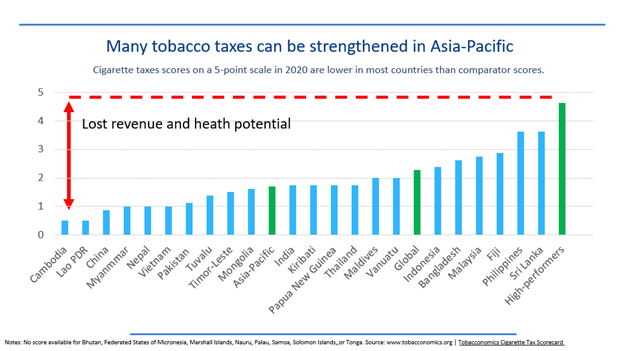

There is room for strengthening health taxes in the Asia-Pacific region. Levies, like those on tobacco or sugar-sweetened beverages, can reduce unhealthy consumption and generate revenue. When the strength of countries’ cigarette taxes is scored against a five-point scale, scores are lower in virtually all Asia-Pacific countries compared to the highest-performing countries (See figure below). Globally, high-performing countries score 4.6, the global average is 2.2, while the Asia Pacific average is below 2.

Countries could direct additional revenue towards the health sector by increasing the health sector budget or earmarking revenue for health programs. This approach has risks - the government may decrease the general budget in the presence of earmarked funds – but on balance it is something that should be looked at.

The time is right to invest in health

COVID-19 delivered a powerful message that ongoing investment in health systems should be a priority for every government. The pandemic primed finance ministries and other non-health stakeholders about the importance of efficient and effective health service delivery. However, a pressing need remains to advocate for resources that support prevention and preparedness, particularly as many non-health sectors that suffered during the pandemic compete for the attention of policymakers. By harnessing political will, speaking the language of their finance colleagues, strategically allocating funding, and implementing win/win tax options, health officials can do more with the domestic resources they have while also making a stronger argument for increased investments in health.

The authors would like to acknowledge Somil Nagpal and Aditi Nigam for their part in writing this blog.

Join the Conversation