Industry participants discussing BPO expansion plans. © Edson Bañare Philippine Information Agency (PIA) Region 6. Used with the permission of the PIA. Further permission required for reuse.

Industry participants discussing BPO expansion plans. © Edson Bañare Philippine Information Agency (PIA) Region 6. Used with the permission of the PIA. Further permission required for reuse.

There will be more improvements, as our internet infrastructure undergoes further upgrades. Our National Fiber Backbone and Broadband ng Masa projects will also deliver high-connectivity and high-speed internet. We are prioritizing geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas.

—President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., State of the Nation address, July 24, 2023

Elena is a resident of Donsol, a municipality in Sorsogon, the southernmost province in Luzon.1 Although near a tourist spot, Elena’s barangay (village) lacks Internet connection. She spends P40 ($0.70) traveling to and from a computer shop at the poblacion (town center) where she pays P25 ($0.50) an hour for internet access. In total, one-hour of internet costs her P 65 ($1.20) a day or P 1,950 ($35) a month.

Digital divide is expanding

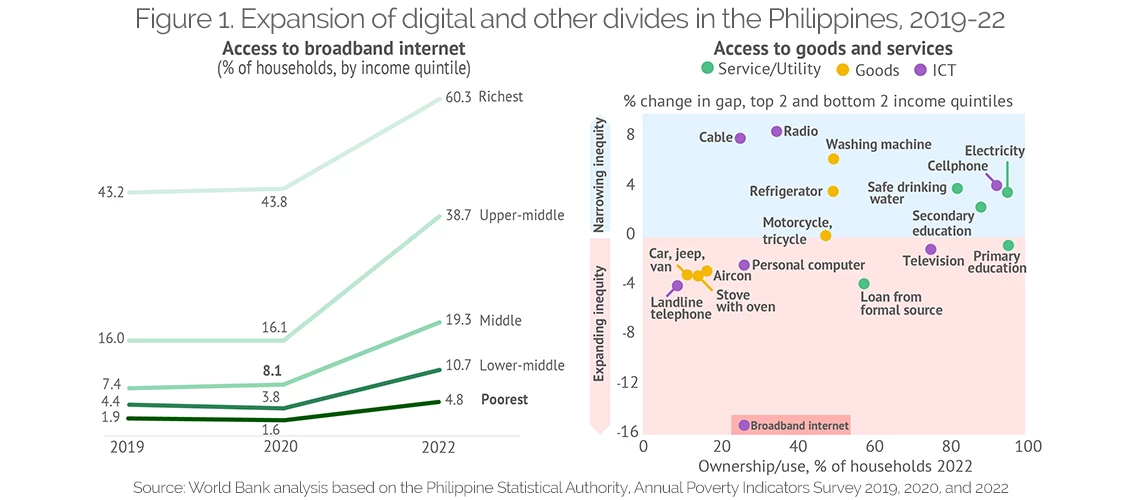

The access gap in broadband internet between the rich and the poor in the Philippines has been rapidly expanding, making digital opportunities out of reach for many. From 2019 to 2022, access to fixed broadband increased by around 20 percentage points for the richest 40 percent of the population, against less than 3 percentage points for the poorest, and around 7 percentage points for the lower-middle income group. In three years, the broadband access gap increased by 16 percentage points, from 26 to 42, between the top two and bottom two income quintiles (Figure 1).

Broadband internet stands out for its increasing disparity in access in contrast to other public and private services, utilities, and goods. The Philippines has made progress toward universal access to safe drinking water, electricity, and education, accompanied by a decrease in inequity; similarly, the availability of cars, air conditioning, and bank loans has increased. However, broadband internet penetration remains low, and the inequity in access has significantly widened. If this trend continues, the digital divide may grow as the key determinant of broader inequity in access to opportunities, and digitalization of public and private services may not effectively contribute to poverty reduction.

Poor internet limits access to opportunities

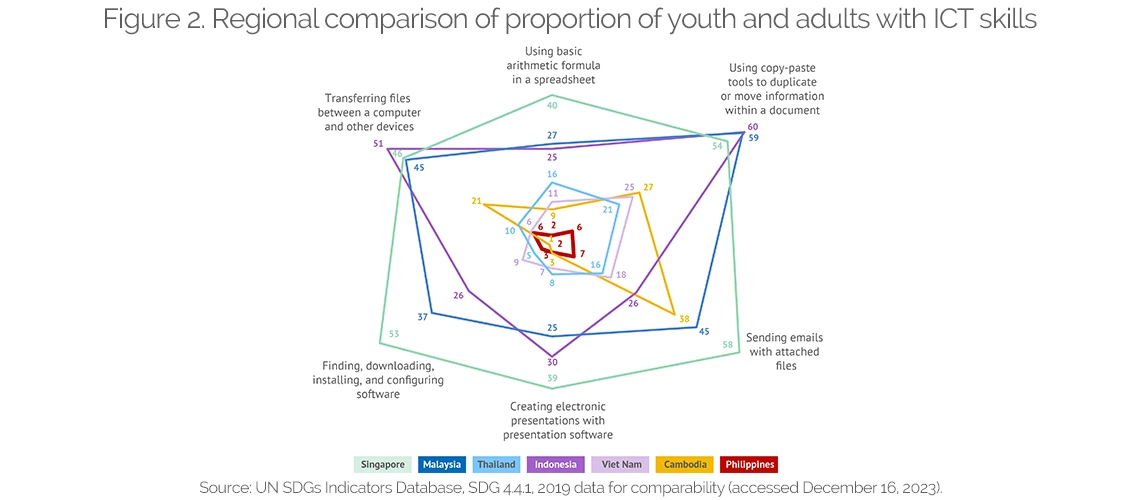

Despite the potential of digitalization in spurring economic growth, poor internet infrastructure constrains digital opportunities for citizens and businesses, as experienced by Elena. If majority of children from low-income families cannot learn with computers connected to internet either in schools or at home, the large deficits in digital skills in the Philippines will not prepare youth and adults for future jobs (Figure 2). Poor internet access also leads to poor technology adoption and limited innovation and productivity growth by firms, especially the micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Fiscal and economic consequences

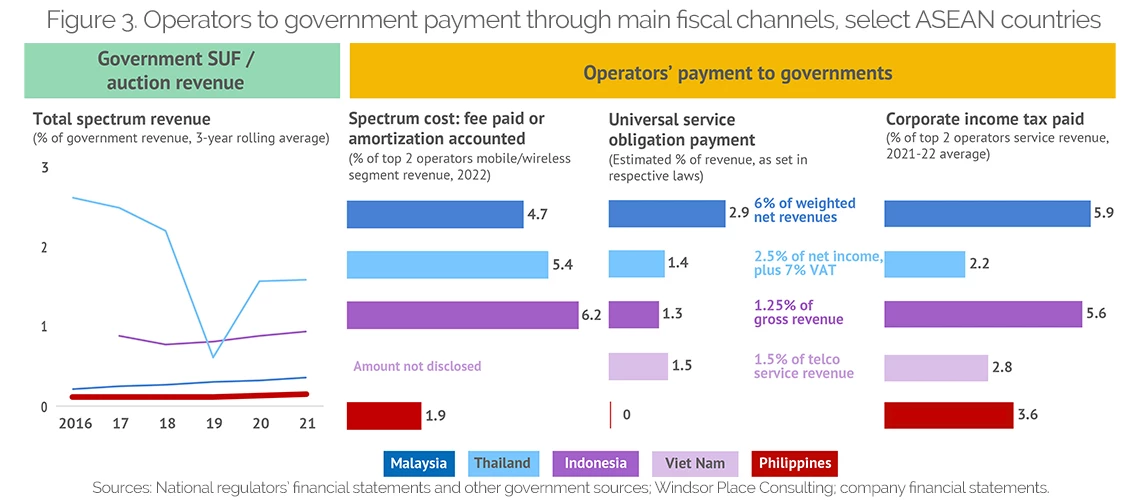

Governments worldwide are tasked with making fiscal policy decisions that strike a balance between generating revenue from spectrum allocations, funding universal service initiatives, and ensuring the sustainable growth of the telecommunications sector. In the Philippines, the ratio of spectrum revenue as a percentage share of total government revenue is 3 to 10 times lower than its ASEAN middle-income peers. The Philippines also collects less direct or indirect taxes from the sector through universal service obligation payment and corporate income tax (Figure 3).

The industry calls for further support from the government to address infrastructure challenges inhibiting the equitable delivery of connectivity across the country. However, the government lacks sufficient policy options or fiscal space for innovative business models to address the digital divide that the market alone cannot resolve. Unlike most regional peers, the country does not have a universal service fund (USF) to ensure that telecommunications services are available to all citizens, regardless of their geographic location or income level. Top operators are not obliged to expand rural network coverage when renewing their license for operation or radiofrequency spectrum, due to the country’s outdated licensing framework.

Policymakers could consider starting with immediate changes to increase internet access for Filipinos, as discussed in "Updating policies to upgrade the Internet for all Filipinos". They could also implement mid-term reforms like rearranging radio frequencies to improve wireless networks, licensing and allowing access to spectrum per subnational regions to incentivize technology deployment more suited to geographic and socioeconomic conditions and trying out spectrum auctions where telecom companies bid for rights to use certain parts of the spectrum. These steps could provide fiscal options to eventually lower broadband prices and expand coverage in rural areas.

The cost of inaction on broadband policy reforms—loss of growth opportunity, people remaining unequipped for future jobs and widening of the digital divide—is too high for the Philippines. Updating policies to upgrade internet infrastructure can accelerate the expansion of digital opportunities and spur faster, inclusive economic growth.

To learn more, see Better Internet for All Filipinos: Reforms promoting competition and increasing investment for broadband infrastructure.

1Elena (not her real name) was a respondent in a field survey on GIDAs conducted by Better Internet PH in 2019.

Join the Conversation