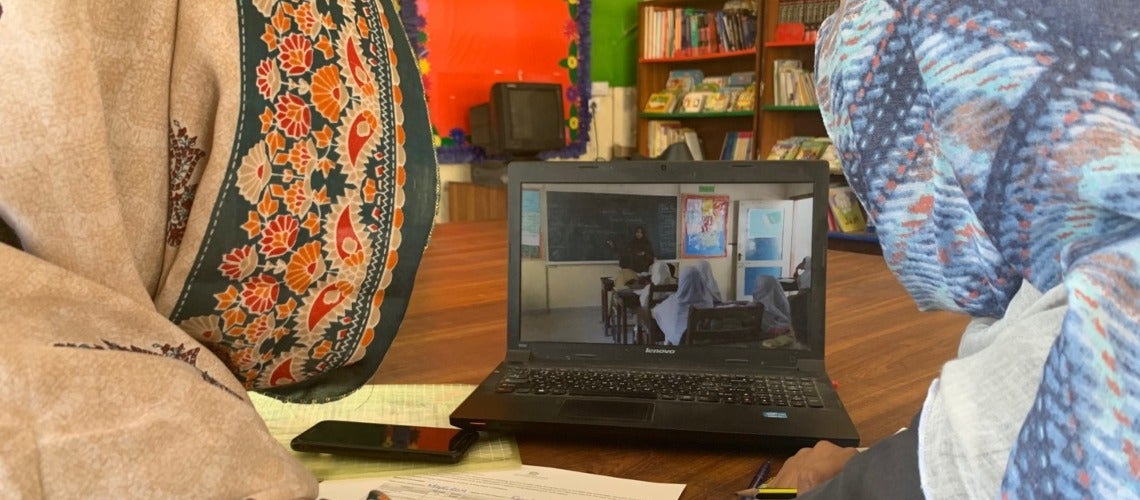

Using a video of a teacher teaching a class to assess principal candidates. Copyright: Nadia Naviwala

Using a video of a teacher teaching a class to assess principal candidates. Copyright: Nadia Naviwala

Public education systems struggle to define the role and responsibilities of administrative vs. pedagogical leaders and fail to catalyze continuous support to teachers and increase student learning. Even when public officials see the importance of school leadership, successful experiences in selecting and supporting leaders are often found outside the public education system. So, how can public systems learn from those successful practices to strengthen school leadership?

While discussions on delivering quality education tend to jump to a discussion on teachers, a large and diverse body of literature demonstrates that strong principals are the single most effective lever to raising learning outcomes after teachers (see resources at the end). Leveraging principals for learning requires seeing them as administrative managers and school leaders who support teachers to increase student learning.

Fours steps to great school leaders

In Pakistan, The Citizens Foundation (TCF) is a non-profit school system for children at risk of being out of school. With 1,450 purpose-built schools and another 380 government schools under its management, it has been part of a transformation of learning in Pakistan: 95 percent of TCF students pass the final examinations at the end of 9th and 10th grades (60 to 70 percent pass in Pakistan) in 2021.

The school chooses leaders using a process that has been successful in finding strong principal candidates and supporting them in their roles. This process, outlined below, could be replicated in other low-resource settings.

Step 1: Selecting candidates with potential

To select strong school leaders, candidates participate in a day-long Principals Assessment Center session organized around where the potential candidate would work if selected for the job. The assessment center is a series of tests, analytical activities, and games observed and scored by a four-member panel. The panel scores candidates on detailed rubrics that breaks down the elements of strong school leadership:

- Capacity (intellectual ability): subject knowledge, observation skills, clarity of thinking, problem-solving

- Achievement (experience): graduate degree, teaching experience, leadership skills, perseverance

- Relationships (building trust): respect for others, conflict resolution, communication skills

- Passion: fit with the institution’s vision

Candidates must achieve a minimum score to be hired as principals.

Step 2: Training and mentoring school leaders

Once hired, principals get a five-day training on mission, values, roles, responsibilities, key performance indicators, real scenarios, and principals’ best practices from seasoned education managers. The training also introduces them to the day-to-day administrative challenges of applying what they have learned.

During a week of shadowing a seasoned principal, new principals learn how to implement the components of their pre-service training. The shadowing allows them to observe processes in practice, how school culture is maintained, how timetables and tests are made, day-to-day challenges, how to guide teachers, and how to engage parents.

Step 3: Managing and incentivizing school leaders

After one year in the system, all principals go through an annual assessment where they are scored on a Principal Quality Index for their effectiveness as school leaders. The index scores the parameters on which they were selected and adds two more for academic and administrative leadership.

Internal evaluators certified through a rigorous selection and training process spend a day with each principal and the education manager. They aim to understand how the principal has focused and delivered on her key priorities for the academic year, what kind of support she has provided the teachers and what role the principal has played in strengthening the school culture. Evaluators complete class observations and then compare their observations to one filled out by the principal in her regular support to teachers to ensure alignment. They also probe into a principal’s insights on her teachers and students and triangulate the information with other data points available in the school to gauge whether support is adequate. Principals must clearly understand their school’s performance based on data she regularly collects and maintains.

The final score for each principal is quantitative and is delivered with feedback and negotiated targets for improvement for the coming year. The process recognizes that information that may be unique to a school or principal may not be captured in the rubrics.

The score—along with other data such as student performance—is used to assign every principal a performance rating. Qualitative information is also factored in, such as if the principal is new and has taken over a very challenging school or if there has been significant improvement in the past year.

Principals are given one of five ratings: outstanding, above expectations, meets expectations, below expectations, or needs improvement. Each category gets a performance bonus added to their monthly salaries. Needs improvement principals are put on a performance improvement plan. If they do not improve, they will not continue with the institution. Strong performance in various categories is recognized at award ceremonies.

Step 4: Supporting school leaders

The model combines accountability and continuous support. Support comes in several forms:

- Annual training through the Principals Academy.

- A network of the strongest principals is put into a Whatsapp group with other principals. This group is used for professional, day-to-day communications. Line managers of principals are part of the WhatsApp group to offer guidance, solutions, and quick approvals.

- Principals get support from their managers, who have strong credentials in education and quality management. They may be former principals or have advanced degrees in education.

Introducing the model in other countries

How can public systems introduce many or all these steps to boost the quality of their school leaders? The key is to define the characteristics and capabilities of a strong school leader and then organize systems for hiring, training, support, and performance management against those clearly defined expectations.

Many highly effective public systems have similar models to find, train and support principals. Taking these steps in developing countries is possible. Countries like Peru have elevated the importance of school principals in catalyzing change; hence they take recruitment and support seriously. Countries like Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and the Dominican Republic, to name a few, have moved into defining the role, competencies, and responsibilities of school principals. Jamaica has developed a comprehensive principal’s career with several steps. To maximize impact on learning, the more steps taken, the more impactful the reforms can be.

Other resources:

Management capacity and service delivery - WB website

Blog: Will a crisis force us to rethink school leadership? Insights from a South-South Exchange

Blog: Evolution of school principal training: Lessons from Latin America

Blog: The principal makes the difference

Blog: Are good school principals born or can they be made?

Book: Leverage Leadership 2.0: A Practical Guide to Building Exceptional Schools

Blog: The School Leadership Crisis ( Part 1, Part 2 )

Join the Conversation