Los ministerios de educación en todo el mundo buscan garantizar la continuidad del aprendizaje para los niños y jóvenes a través de la educación a distancia.

Los ministerios de educación en todo el mundo buscan garantizar la continuidad del aprendizaje para los niños y jóvenes a través de la educación a distancia.

Across more than 170 countries, some 1.5 billion students have seen schools close as part of their governments’ response to the coronavirus (COVID-19). Now, ministries of education around the world try to ensure learning continuity for children and youth through distance learning. In most cases, efforts involve the use of various digital platforms featuring educational content, and a variety of educational technology (EdTech) solutions to keep communication and learning spaces as open and stimulating as possible.

The paradox facing all countries is that, while these technological solutions seem to be the best way to minimize huge learning losses during the crisis (especially for vulnerable students), they also risk further widening equity gaps in education . Thus, if the digital gap in education were to increase while schools are closed, learning inequality and learning poverty would also inevitably increase. Learning continuity would then be ensured for some but denied to others.

Initial efforts are focusing on ensuring that all students have access to the Internet, the first dimension of the digital gap. This would allow all students to access online learning materials and digital platforms with educational content. However, even in rich countries where Internet connectivity is all but universal and there is little gap in access, the COVID-19 crisis has illuminated two more dimensions to the digital gap.

The second dimension is the digital use gap: without direction, engagement with online content is less sophisticated and less learning-oriented for students from poorer socioeconomic backgrounds. The third dimension is the school digital gap: the capacities and capabilities of each school to provide individualized, or suitably levelled and sequenced, digital learning for students; to promote and monitor engagement with these materials; and provide to feedback that helps maximize learning outcomes. For example, one school might be sending printed materials only or suggesting that students watch videos aimed at the general public, while another school is able to continue classes virtually or initiate creative ways of using digital apps for collaborative learning and individualized student support. The vast disparity in schools’ capabilities makes it easy to see why this is the most relevant digital gap for ensuring that students can keep learning during the pandemic.

Since nobody knows more about schools than their principals, we have looked at the Principals’ Questionnaire in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018 to see what they said about the readiness of their schools and teachers to create and manage digital learning experiences for students. Their responses bring some hope, but also a realistic and somewhat disappointing picture.

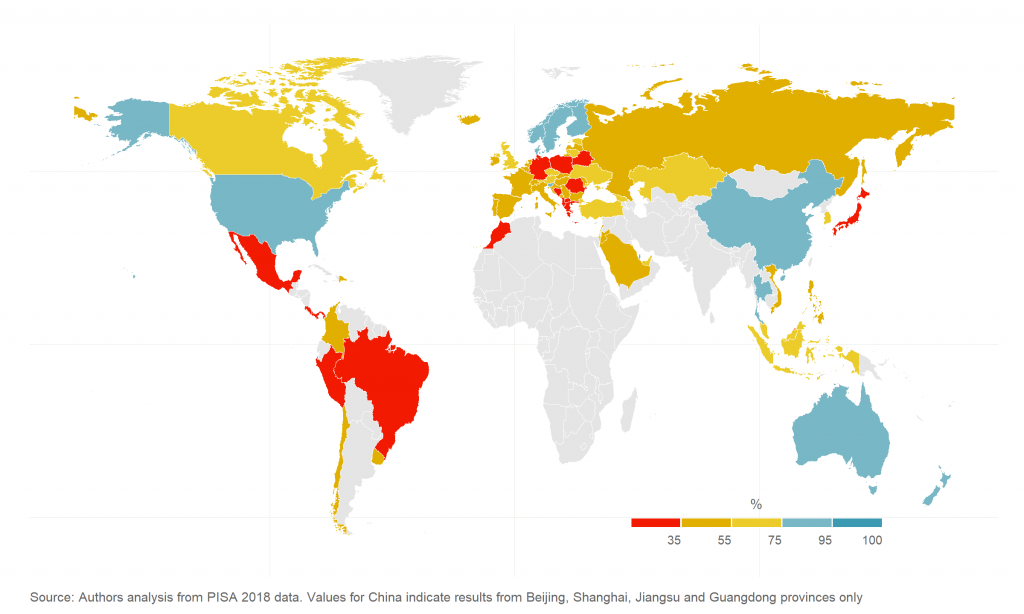

Do principals agree that there is an effective online learning support platform available to their students?

Principals in slightly more than half of education systems surveyed said that most 15-year-old students are in a school without an effective online learning support platform. This is the case in all participating countries from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), most of those from Europe and Central Asia (ECA) (not the Baltics, Turkey, and Kazakhstan) and all of those from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), except Qatar, plus a considerable number of high-income and OECD member countries (France and Portugal had 35 percent of students with no access, Germany 34 percent, and Japan 25 percent). While most countries are in the range of 35 to 70 percent, universal access to such platforms is within reach only for a few countries, including all the Nordic countries, Singapore, Qatar, and the four Chinese provinces participating in PISA 2018, and to a lesser extent Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the United States. Overall, most countries are in the range of 35 to 70 percent of students attending schools in which the principal reports the availability of effective online learning support platforms. Hence the world’s education systems remain very far from universal availability of effective online platforms for student learning.

Figure 1. An Effective Online Learning Support Platform is Available

Percentage of 15-year-old students whose school principal agreed or strongly agreed

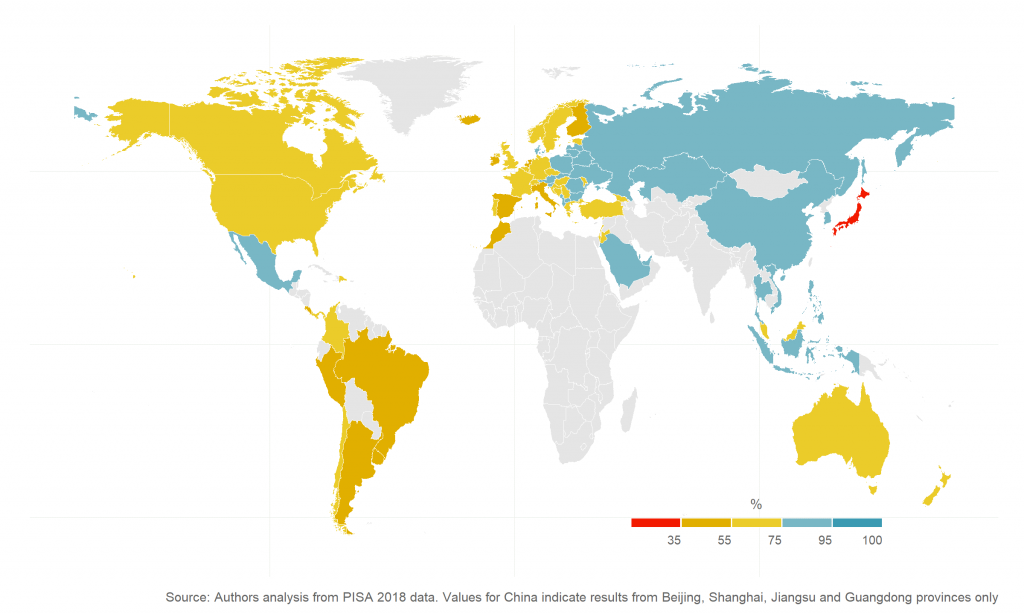

Do teachers have the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction?

Principals had a much more positive opinion on this question. With just a few outliers (most notably, Japan), most countries have around two-thirds of 15-year old students in schools whose principals think their teachers have the technical and pedagogical skills for digital learning. High-income OECD members, again, do not fare better than middle-income countries. Differences between regions are comparatively small, although LAC and MENA lag behind ECA and East Asia and Pacific (EAP). In the COVID-19 crisis, the responses on this question offer some hope, though two-thirds seems low for teachers while at the same time raises concerns about the remaining third, whose teachers do not have skills that are now indispensable for successful digital learning during the school closures.

Figure 2. Teachers Have the Necessary Technical and Pedagogical Skills to Integrate Digital Devices in Instruction

Percentage of 15-year-old students whose school principal agreed or strongly agreed

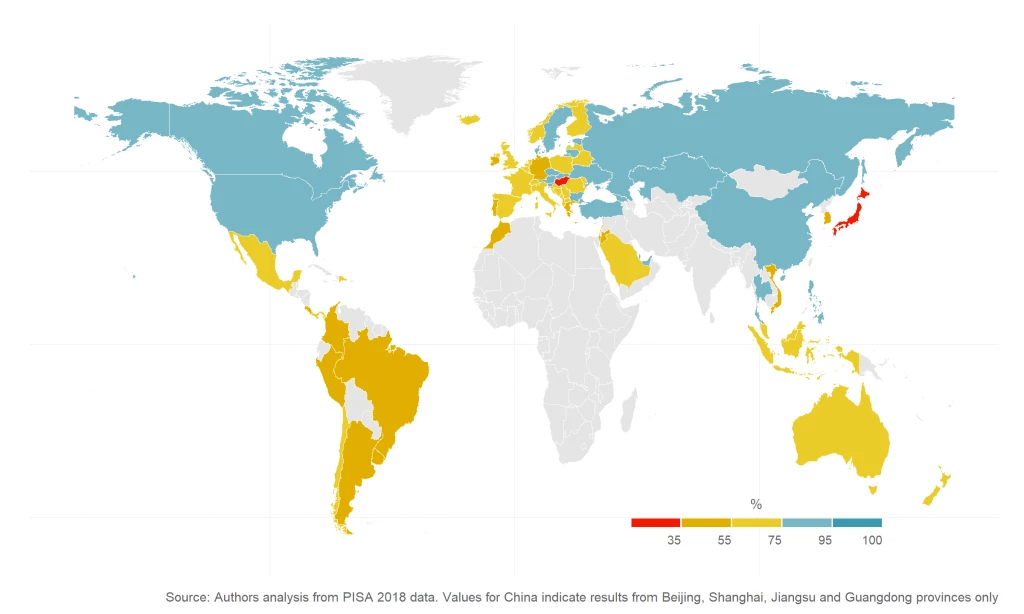

Are there effective professional resources to learn how to use the digital devices that are available to teachers?

Principals were reasonably positive in their views on this question. For most countries, between 45 and 80 percent of students are in schools whose principal considers that effective resources exist for teachers to use the digital devices available, with quite a few countries reaching 90 percent and higher. Here again, rich countries are not particularly different from middle-income countries across LAC, MENA, EAP, and ECA. The two outliers are Japan and Hungary, where principals report a lack of such resources (affecting 19 and 29 percent of students, respectively). With close to a third of students having teachers who lack access to these professional resources, the COVID-19 crisis increases the urgency for ministries of education and private sector providers around the world to create and make available more and better resources for teachers (and now parents as well).

Figure 3. Effective Professional Resources for Teachers to Learn How to Use Digital Devices are Available

Percentage of 15-year-old students whose school principal agreed or strongly agreed

Conclusion: Digital gaps in education are important to address in response to COVID-19 and future crises

When it comes to education inequalities, the digital paradox is inescapable. In most of the 82 education systems participating in PISA, there is a positive correlation between the three variables described above and student socioeconomic status (a positive and statistically significant correlation is found in 46, 47 and 56 countries for each of the three variables described respectively). Thus, during COVID-19 and any future need for intermittent school closures, digital learning has the potential both to avoid widening learning inequalities and, paradoxically, to exacerbate them.

The good news is that most school principals are quite confident about the pedagogical skills of their teachers and the availability of resources to help them use digital learning while students remain at home. It is critical now to ensure universal access to the Internet, as this can enable schools to use EdTech effectively, in age-appropriate ways, as part of their regular instruction. The aim is a smooth transition to distance learning, to allow continuity of learning during any future disruption in school operations.

Join the Conversation