At the heart of Kabul City in Makroyan 3, lies the all-boys ‘Abdul Hadi Dawi’ school. Despite having 3,000 students, there are no latrines, only a remote plot of land dotted with containers for the students to use. The school is also located near the Supreme Court, an area with potential security risks.The Abdul Hadi Dawi School encapsulates many of the problems with the education system in Afghanistan.

There is little evidence of high-quality instruction or learning happening in the classroom. And neither were teachers being assessed on their performance nor the quality of their teaching.

Improving learning is a priority for Afghanistan. Therefore, the government of Afghanistan sought our support to document the reality of primary education in Afghanistan and identify bottlenecks in schools that impede the delivery of high-quality education.

Thirty-two schools participated in our pilot study in Kabul city in April 2017. Our findings break new ground and are based on SABER Service Delivery methodology already tested in the Africa region through the Service Delivery Initiative.

Our survey provides indicators necessary to track progress in student learning and inform education policies to provide high-quality learning environments for both students and teachers. The indicators are standardized, allowing comparisons between and within nations over time.

Here’s an overview of what we discovered:

1. How much time is spent teaching?

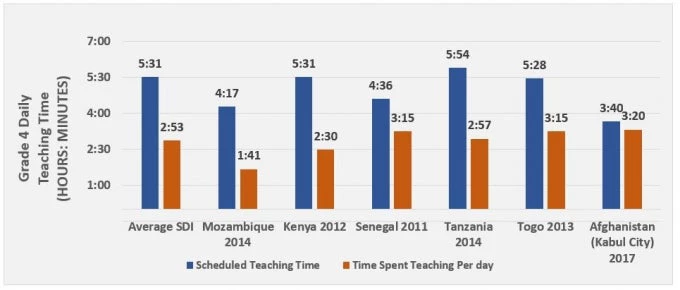

Based on the survey results, a lesson in Afghanistan public schools lasts a maximum of 45 minutes in the spring and 35 minutes in the fall. Grade 4 Students spend an average 3 hours and 40 minutes in school. Since the shifts are very short, with a break of 20 minutes, they spend 3 hours and 20 minutes in classrooms learning. This is above the average in African countries such as Kenya and Mozambique, which respectively provide grade 4 students with 2hours and 30 minutes and 1hour and 41 minutes of instructional time per day despite longer scheduled teaching time with lengthier breaks between classes.

Out of 32 schools visited in Kabul city, 15 had triple and 16 had double shifts indicating less time for students to learn.

2. Are teachers present in schools?

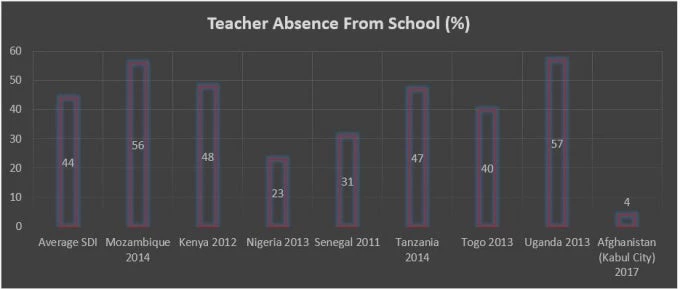

During our pilot in Kabul city, on the day of visits, out of 324 teachers who were randomly selected, 13 teachers were absent from school. Afghanistan’s situation is not unique: teacher absence has been reported to be between 23-57 percent in countries we previously evaluated. Preliminary observations indicate that teacher absentee is not as widespread or common as in other comparable countries. However, further observations are needed to confirm that trend.

3. Is student attendance a problem in Afghanistan?

Student absence ranges between 2 percent and 35 percent on the day of our visit depending on the neighborhood and the gender makeup of the school. Absenteeism is more pronounced in boys’ schools, with a rate that is 60 percent higher than girls’ school in Kabul city. Several school principals and teachers noted that boys generally need to work to provide for their families in addition to attending to school.

4. How do teachers interact with students in the classroom?

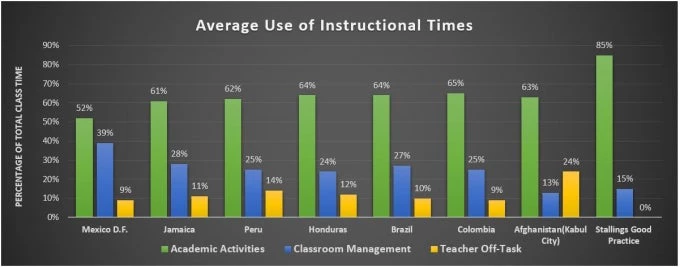

To quantify what teachers do in the classroom, we conducted classroom observations using the Stallings Classroom Snapshot to record the range of activities teachers accomplish during the lesson. This method uses a standardized coding grid to register the activities and materials being used by a teacher and students over the course of a single class. As shown in the graph, the total percentage of teachers not being engaged in academic activities or “off-task” (i.e. either doing classroom management or being idle) is very similar to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, such as Brazil and Honduras indicating students have less time to learn.

5. Do teachers have the skills to teach effectively?

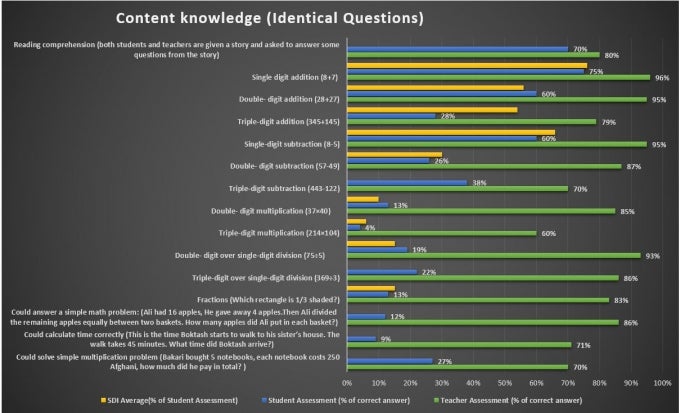

Students (grade 4) and teachers (teaching grades 3-6) were assessed on the math and language (Dari/Pashto) subjects. Teachers were assessed on their mastery of grade 4 level mathematics and language, in addition to their pedagogical skills. The test involved asking teachers to grade a mock student test and suggest a correct answer to incorrect responses.

Overall, 79 percent of the teachers could perform triple-digit addition, as opposed to 28 percent of students who mastered this operation. The average SDI countries results for students who can correctly calculate triple- digit addition is 54 percent. When it comes to solving a simple math story (See Graph Below), 86 percent of the teachers and only 12 percent of the students managed to understand and solve the problem.

Going back to our initial question, how bad the learning crisis really is in Afghanistan.

Based on the limited pool of students and teachers we met, it is obvious that Afghanistan reflects education trends seen in other parts of the world. Namely—and strikingly-- that teachers often lack the skills to teach effectively.

As noted in the recent World Development Report, average grade 6 teachers across 14 Sub-Saharan countries were found to perform no better on reading tests than the highest-performing grade 6 students.

In Afghanistan, our evidence suggests the same. When given a story and asked to answer questions about it, both students and teachers demonstrated similar low levels of comprehension, implying that teachers lacked basic necessary skills to perform adequately in the classrooms.

As we finalize our survey in 200 schools in 20 provinces of Afghanistan, we will provide more insights on the learning crisis in Afghan schools. We hope our data will help Afghanistan improve its education system so that all Afghan children can learn and teachers can acquire the skills and resources to perform effectively.

Join the Conversation