Afghans represent the world’s largest protracted refugee population, and one of the largest to be repatriated to their country of origin in this century .

More than seven million refugees returned to Afghanistan between 2002 and 2017, mainly from Iran and Pakistan .

Afghan returnees now make up as much as one-fifth of the country’s estimated population.

At the same time, conflict-induced population displacement within Afghanistan has sharply increased due to the escalation of insecurity across the country.

In an already difficult context, large-scale internal displacement and returnees from abroad have strained the delivery of public services and increased competition for scarce economic opportunities for both the displaced and the rest of the population.

Afghans are living under difficult economic conditions. More than half of all Afghans lived below the national poverty line in 2016-17, and many more are vulnerable to falling into poverty .

To support struggling communities through scarce humanitarian and development assistance is challenging but necessary.

But policymakers struggle with many questions.

First, who are Afghanistan’s displaced people, and how do their living conditions, vulnerabilities and opportunities differ from those Afghans who have never had to leave? Is someone who was a refugee 15 years ago but repatriated to Afghanistan 10 years ago considered a returnee, in the same way a returnee who returned last month is?

Second, where do internally displaced persons (IDPs) and returnees settle, and will they be able to remain in their “temporary” locations? Should they be hosted in cities or should investment be directed towards their places of origin in rural areas?

To provide some answers, the World Bank prepared a note on the socio-economic conditions of IDPs, returnees (former refugees who returned to Afghanistan between 2002 and 2014), and compared them to host communities’ using national household survey data[1].

Importantly, the results document socio-economic conditions just before the transfer of security responsibilities from international troops to the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) in 2014, which was associated with a subsequent decline in aid, both security and civilian, and a sharp drop in economic activity.

The results presented here cover the largest return of Afghans to the country since 2002 but precede the more recent large-scale return of Afghan refugees from Pakistan in 2016 and 2017.

The results reiterate that Afghans live in difficult economic situations and with limited resources (in terms of human and physical capital). Moreover, and perhaps more interestingly, the results point to noticeable differences in socio-economic outcomes between returnees, IDPs, and hosts.

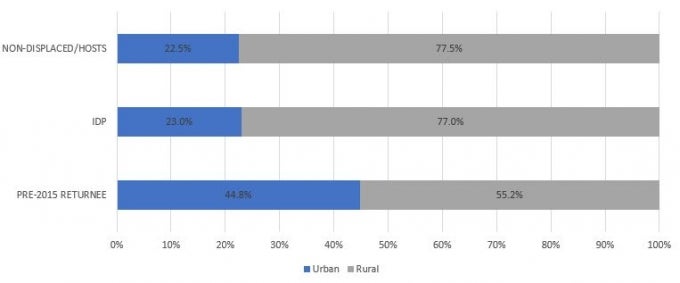

We observe that in 2013-14, Afghanistan’s returnees were more urbanized than other groups . Almost half of all pre-2015 returnees lived in urban areas, compared to less than one-quarter of IDPs and hosts (Figure 1). The sharp difference in rates of urbanization of returnees relative to other groups was also associated with differences in other dimensions of socio-economic outcomes such as education, dwelling characteristics, and labor market outcomes.

Figure 1: Percentage of households living in urban and rural areas, by displacement group, 2013-14

Educational attainment and exposure to formal education were low across all groups (with more than half of Afghans having no formal education) and characterized by sharp gender disparities and urban-rural differences.

Only 35 percent of Afghans can read or write, and few have ever attended formal school, particularly in rural areas .

Literacy rates in urban areas are almost double those in rural areas.

Against this backdrop, pre-2015 returnees had substantially higher literacy rates (47 percent) than did IDPs (36 percent) and hosts (34 percent). Returnees also had the highest rates of formal school attendance and thus returnees showed the highest educational levels, with 55 percent reporting some form of formal education (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Literacy rates and rates of formal education among pre-2015 returnees, IDPs, and hosts, by location

While labor market outcomes were very poor across all groups, returnees had a higher chance of employment and IDPs had the lowest employment rates.

In general, access to secure, salaried jobs was low across all groups with the highest rates found among returnees (Figure 3). IDPs, on the other hand, had the most insecure jobs – almost every fifth IDP worked as casual daily labor and a third as unpaid family worker.

The elevated overall prevalence of unpaid family work across the three groups was primarily driven by high rates of such work in agriculture in rural areas.

Figure 3: Employment types, by displacement group and location

Aligned with a higher likelihood of living in urban areas of the country, returnees enjoyed better dwelling characteristics and greater access to infrastructure services.

For example, over 60 percent of pre-2015 returnees had access to improved sanitation, compared to 50 percent of IDPs and less than 40 percent of hosts. Almost 82 percent of returnees had access to safe drinking water, compared to only 50 percent of IDPs and 62 percent of hosts .

One indicator on which returnees lagged behind IDPs and hosts was dwelling ownership, there was a 10-percentage point gap in dwelling ownership between hosts and returnees.

The dire security situation and economic downturn of recent years imply that refugee returns and internal displacement strain the fragile public service system of Afghanistan.

This affects not only displaced people, but all Afghans. This note adds to our understanding of differences in socio-economic outcomes and needs of displaced people and hosts which is vital to a robust policy response and an effective management of the displacement challenge, a critical aspect for Afghanistan’s economic and political future.

Join the Conversation