Agriculture students learn how to use the latest technology to better manage scarce land and water resources and withstand the onslaught of climate change.

Agriculture students learn how to use the latest technology to better manage scarce land and water resources and withstand the onslaught of climate change.

Travelling through India’s northeastern state of Assam, we were pleasantly surprised to meet Kavita, a young agriculture student, and hear her talk knowledgeably about how this primarily agricultural state could usher in a new green revolution. She had learnt to read satellite images and program drones so that the right amounts of inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides could be applied to the crops at the right time. And, she had learnt it all through the remote classes she could now attend from her village home.

Further south, in Tamil Nadu, far removed from Assam and with very different agricultural needs, we were equally delighted to meet Bharthiban who studies veterinary medicine. The young man excitedly described how he had used cattle simulation models to become proficient in artificial insemination because his university – the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University – had recently been equipped with suitable digital platforms that facilitated this.

India is one of the world's leading producers of agricultural commodities, producing more milk and pulses than any other country. It is also the second largest producer of rice, wheat, fruit and vegetables. But, in the face of climate change, water scarcity, a rising population and decreasing land available for cultivation, India will need to ramp up the use of agricultural technology and accelerate innovation if it is to continue to be a food secure nation and remain at the forefront of global food production.

For this, the country will need to infuse its traditionally labor-intensive farm sector with a vast pool of trained agricultural professionals who are proficient in the latest practices and technology. At present, however, India faces a huge shortfall: it needs almost 100,000 graduates in agriculture and related areas but has about half that number.

To increase the number of technologically-savvy agricultural graduates, the World Bank’s National Agriculture Higher Education Project is helping India’s apex body for agricultural research and education - the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) - to raise the country’s 74 agricultural universities to world standards, with revamped curricula and forward-thinking classes.

More than 100 vocational skill-based courses have been introduced, and the curricula of 79 disciplines have been re-designed to make them more contextual and relevant in terms of competitiveness and employability.

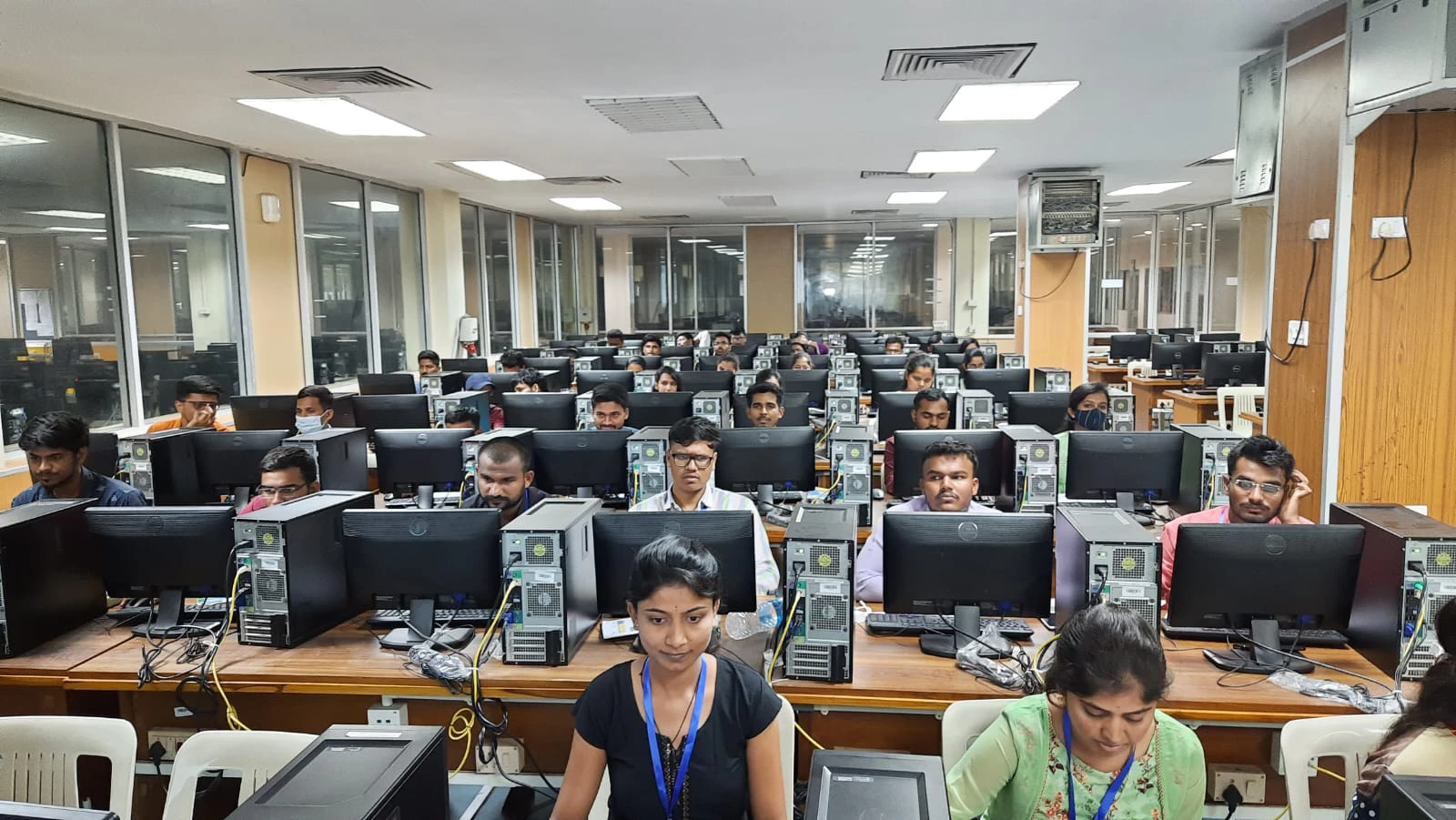

Since traditional in-person teaching, together with online learning, is one of the best ways to educate a large number of young people at lower costs, many universities have established virtual classrooms, allowing students to see places they cannot visit, watch events they would rarely encounter, and learn directly from national and international experts.

Dr R.C. Agrawal, Deputy Director General in charge of Agriculture Education and National Director, NAHEP, calls this a paradigm shift that will lead “institutions to organically evolve into multi-disciplinary clusters offering professional education both seamlessly and in an integrated manner”.

And the impact of these efforts is becoming increasingly evident. Between 2017 and 2021, more than twice the number of students enrolled in agricultural universities throughout India - from some 25,000 to nearly 55,000 – making agriculture a viable career option for young people. What’s more, the share of female students climbed to over 45 percent. The quality of graduates also improved, with their placement rate rising from 42 percent to over 60 percent, indicating growing job opportunities for such disciplines.

Importantly, ICAR’s efforts will not only benefit agriculture but will impact society at large. Apart from reducing the carbon footprint of food production ¬ - agriculture contributes 29 percent of global GHG emissions – the use of the latest technology such as GPS, remote sensing and drones will help the country manage scarce land and water resources. Data analytics and artificial intelligence will also enable farmers to better withstand the onslaught of climate change.

Countries like Australia, Israel, the Netherlands, South Korea and the United States have already taken a lead in this regard, with agricultural technology reducing operational costs and enabling less resource-intensive growth.

Unlocking the transformational power of technology will completely change the way India produces and distributes food. It will also bring the country one step closer to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision for a digital India: “I dream of a digital India where quality education reaches the most inaccessible corners driven by digital learning.”

This will, perhaps, unleash a new force that will drive India’s evergreen agricultural revolution.

Join the Conversation