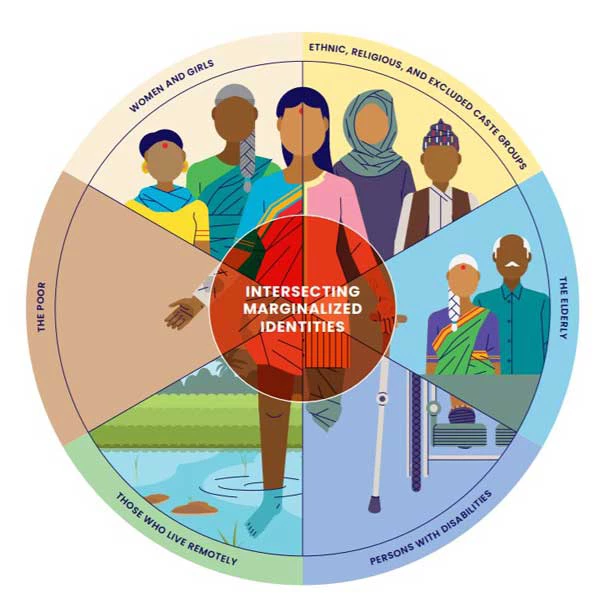

Major social exclusion factors observed in South Asian countries include gender, age, disability, economic status, geographical location, as well as ethnic, religious and caste status

Major social exclusion factors observed in South Asian countries include gender, age, disability, economic status, geographical location, as well as ethnic, religious and caste status

On April 25, 2015, when a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Nepal, Bandita recalls the urgency with which she moved her young children and elderly mother-in-law out of the house.

Once at a ‘safe’ location, her other major concern was her nonagenarian grandmother, infirmed and with limited mobility. Would there be evacuation support for her, and people in vulnerable situations like hers? Would her grandmother be able to find shelter? Would she have access to food, water, medicine?

In the aftermath of the earthquake, the poor and the marginalized sections of Nepal suffered immense losses due in large part to an absence of adequate knowledge on safety protocols, including how to access evacuation sites, emergency relief and rescue services, and post-disaster assistance packages. These anecdotes bring to the fore questions about who disproportionately suffers due to climate change or disaster events.

Social exclusion remains pervasive in South Asia and has a significant impact on both development and resilience outcomes . But, how exactly does exclusion undermine disaster preparedness, risk management and response efforts? What types of policies, programs and frameworks are necessary to make disaster risk management inclusive for all? These are not concerns limited to developing countries.

Growing up at the foot of the most active volcano in Japan, with a sister who was born with heart disease, and old grandparents, Keiko’s concerns about what preventive actions her family could take when a disaster hit were not very different from Bandita’s.

Similarly, Melody, growing up in earthquake and fire-prone California, felt vulnerable as a child dependent on family, and the Government, to adequately consider children's needs in a disaster-context.

In disaster risk management (DRM) systems, opportunities to advance social inclusion are considered regardless of the individual country's economic level.

Why Inclusion Matters for Resilience in South Asia?

South Asia is one of the regions’ most vulnerable to the impacts of natural hazards, particularly climate-induced extremes . As the South Asia’s Hotspots (World Bank, 2018) indicates, the anticipated increase of temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns will reduce living standards in communities across South Asia.

Shock Waves : Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty (World Bank, 2016) established a strong link between poverty and climate vulnerability. It found that poor people are more likely to be exposed to hazards; lose more as a share of their limited wealth when hit; and receive less support after disasters.

The World Bank’s approach towards Inclusive Resilience in South Asia

Given these pressing challenges facing South Asia, the World Bank’s new publication Inclusive Resilience: Inclusion Matters for Resilience in South Asia (2021) offers a timely contribution to address social inclusion in climate and disaster resilience. The report builds on the World Bank’s flagship report on social inclusion, Inclusion Matters: The Foundation for Shared Prosperity (2013).

While many South Asian governments have made significant and important strides towards addressing social inclusion issues in DRM policies and frameworks, there often remains a gap in translating these commitments into de facto actions on the ground.

Examples of Inclusive Resilience actions from the report:

- Design early warning systems that enable delivery of warning messages to the excluded: Bangladesh is a champion in integrating disability-inclusive DRM. Under the Bangladesh Weather and Climate Services Regional Project (BWCSRP), agrometeorological (agromet) services and early warning systems have opportunities to enhance inclusive communication by breaking barriers based on literacy, poverty, landownership status, disability, and ethnic identity. For example, diversifying message delivery methods (e.g. voice messages, pictograms etc.), customizing information to the needs of excluded farmer groups, and enhancing the “disaster literacy” of community with focus on excluded groups improves access and benefits of agromet systems.

- Make cyclone shelters and services accessible to all: Hundreds of Multipurpose Cyclone Shelters have been built in India through National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project Phase I and II. These shelters were built with universal access design features such as ramps, designed with facilities for people with limited mobility (e.g. elderly, pregnant women, persons with disabilities), and ensure the privacy in toilets and showers. Further, the Shelter Management Committees proactively seek representation from marginalized groups. These measures promote more inclusive access to the shelters.

- Provide tailored support for vulnerable groups throughout the reconstruction process: The Nepal Earthquake Housing Reconstruction Project helped people restore houses in the most-affected districts of the country. Those who met the government’s vulnerability criteria received additional grants to accelerate the reconstruction process. Yet, the majority of the affected population were already poor and marginalized. Pairing financial support with capacity building can empower marginalized groups to access information, understand their own benefits, liaise with masons, engineers and other reconstruction service providers.

- Expand the scope of community engagement to build the resilience truly for the community: In Pakistan, the Sindh Resilience Project is enhancing the Community-based Disaster Risk Management (CBDRM) approach. Adopting a holistic approach to CBDRM and using it to integrate community’s needs across the DRM cycle can enhance participation and ownership of the CBDRM process; thereby enhancing community resilience. Inclusive CBDRM can enhance outreach through non-traditional channels to engage traditionally socially excluded groups such as women, and CBDRM trainings that reflect the needs and constraints of excluded groups.

- Leverage infrastructure investments for enhanced social inclusion outcomes: Sri Lanka is expanding the investment in resilient infrastructure, including through the Climate Resilience Multi-phased Programmatic Approach. To enhance the accountability and transparency process over the lifespan of these investments, establishing a citizen monitoring committee to oversee those infrastructures during the design and construction phase will promote community ownership and contribute to the long-term sustainability of such assets. Where resettlement is required, there are opportunities to provide equal access to land and assets through joint ownership or individual ownership for women.

The Way Forward

Inclusive resilience is about recognizing different forms of social exclusion in our communities and thoroughly considering the ways to address them . The report goes a step further to identify the practical actions that governments, DRM and social development practitioners can take to advance inclusive resilience through resilience investments.

In the case of Bandita’s grandmother, a benevolent neighbor brought her to safety. However, we cannot always count on someone’s good will, we must ensure that effective mechanisms are in place to build resilience that is truly for “ALL”.

This video highlights some of the inclusive resilience actions that DRM interventions can adopt to move in that direction. These actions are practical and do not require significant financial implications either.

We have no reason not to act now.

Join the Conversation