working from the kitchen table

working from the kitchen table

During the pandemic many of us worked from the kitchen table. Public service employees made their kitchens honorary extensions of the ministry or agency in which they worked. Never had the public service gained such access to frying pans and baking ingredients.

Yet government didn’t just continue; in most countries it stepped up as a leader in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As our data shows, many officials were more productive at home not having to commute distractions and having greater flexibility in how they used their time. This message came through in a series of surveys undertaken by the World Bank’s Bureaucracy Lab – in collaboration with its Global Survey of Public Servants consortium partners – on life in the public service. We have conducted surveys, tailored to the specific concerns of each government, with over 110,000 public employees in seven countries over the past two years.

A majority of public officials surveyed feels at least as productive working from home (as they do working in the office) with percentages of officials agreeing that they were at least as effective ranging from 60% (Kazakhstan) to 79% (Colombia). However, we find that getting several basics right in managing government employees remotely is strongly associated with greater productivity and wellbeing in remote work. As illustrated in Figure 4, these basics comprise:

- An adequate workplace (physical space and technology, such as computer and internet)

- Effective remote collaboration with colleagues

- Effective remote leadership and supervision

- Effective organizational support from training to IT support to mental health support, among others

Figure 1. The Basics of Managing Government Employees Remotely

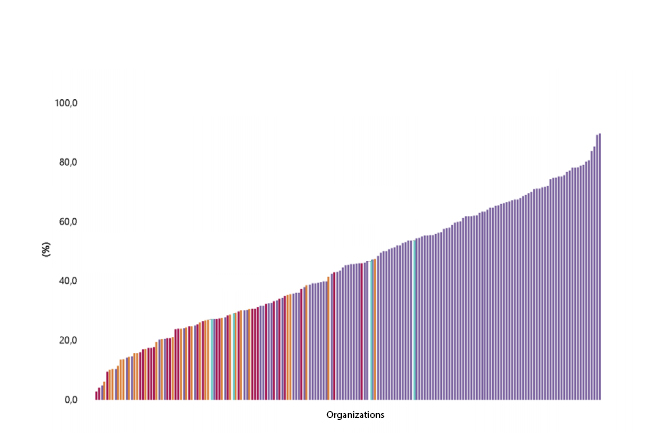

The extent to which these pillars are in place can determine/influence the level of productivity of staff. In many settings, officials were left to operate without these basic elements of their work. Starting with the adequacy of the remote workplace, the share of public employees working remotely that reported lack of internet as a challenge varies between 11% in Brazil and 51% in Ghana. In terms of (lack of) remote leadership, 9% in Colombia and 14% in Chile of public officials indicated that their manager does not supervise their work remotely. And once again, some institutions within a single government do far better than their counterparts. For instance, in Colombia the share of respondents who have received training for remote work varies between 0% and 89% across state institutions, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Proportion of public officials in Colombia who report having received training on remote work, by state institution (blue = central government; purple = regional government; orange = municipalities)

The surveys underscore that in all governments we studied there were organisations and managers making remote work comfortable and productive for their employees; and there were those that were not. For government 'from the kitchen table' to be effective across the public service, the experience of public officials should be regularly monitored. In the first part of this blog post (available here), we argued that governments should give managers new incentives that focus on keeping government running in its now disparate organisational state. But for those incentives to be effective, they must be tied to effective monitoring regimes.

Surveys of public servants provide an important diagnostic to help understand where the basics of remote work are not in place inside government. We encourage others to use such tools to help boost the productivity and support the wellbeing of public employees during remote work – now and after the pandemic – and understand what works in remote management of public employees. An example questionnaire is available for download here.

Doing so will ensure the public service is kept as functional as possible – whether it is in the kitchen or not. Such resilience is likely to become increasingly important in our increasingly uncertain world.

Editor's note: This blog post is part of a series for the 'Bureaucracy Lab', a World Bank initiative to better understand the world's public officials. It is the second of a two-part series on return from telework in government. You can find part I here.

Join the Conversation