What does gender equality mean to you?

What does gender equality mean to you?

Editor's note: This blog post is part of a series for the 'Bureaucracy Lab', a World Bank initiative to better understand the world's public officials.

Author’s note: In this blog, “equal pay” legislation is a law that mandates equal remuneration for women and men for work of equal value. “Non-discrimination” is a law that prohibits gender-based discrimination in hiring.

In the overwhelming majority of countries around the globe (155 of 173 examined by our World Bank report), gender-based discrimination is embedded in the law. Nearly a third of countries have legal gaps in overarching frameworks, employment and economic benefits as well as laws that thwart women’s involvement and advancement in the workplace (UN, 2019). These frameworks perpetuate persistent equalities between women and men in hiring, remuneration, and advancement in the workplace.

Last year, we wrote that the public sector, while not perfect, bodes relatively well for gender equality. Compared to the private sector, it employs a higher proportion of women and pays them a fairer wage. This year, as an increasing share of countries adopt legislation for gender equality in the workplace, we take a deeper dive into Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators and Women, Business and the Law data to look at trends in equal pay and non-discrimination legislation and how they interact with gender equality in the public sector. We find six facts, among them that the public sector leads the way in implementing and championing non-discrimination legislation. Meanwhile, the private sector lags behind.

1. Globally, more and more countries are adopting equal pay and non-discrimination laws.

Between 2009 and 2017, the share of countries with equal pay and non-discrimination laws increased by four and seven percentage points, respectively. The rise in equal pay legislation was largely driven by Sub-Saharan Africa, where six countries adopted EPEW laws in the past decade, and Europe & Central Asia, where four countries did the same.

2. Europe & Central Asia lead the way in equal pay and non-discrimination legislation.

Equal pay and non-discrimination legislation is, perhaps unsurprisingly, most widely adopted in Europe & Central Asia. The European Treaties mandated equal pay for equal work in 1957 and the European Pillar of Social Rights reiterated the principle in 2017.

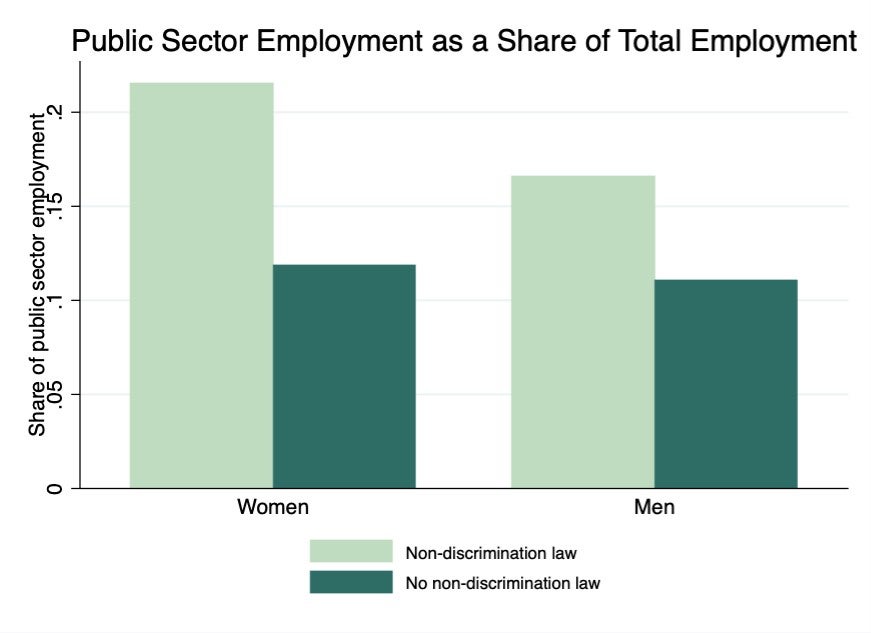

3. Women’s public sector employment is significantly higher in countries with non-discrimination laws than in those without them.

Perhaps women flock to — or receive more job offers in — the public sector in countries with non-discrimination laws. Though, this trend may in fact be driven by higher rates of informal employment, especially among women, in non-ND countries.

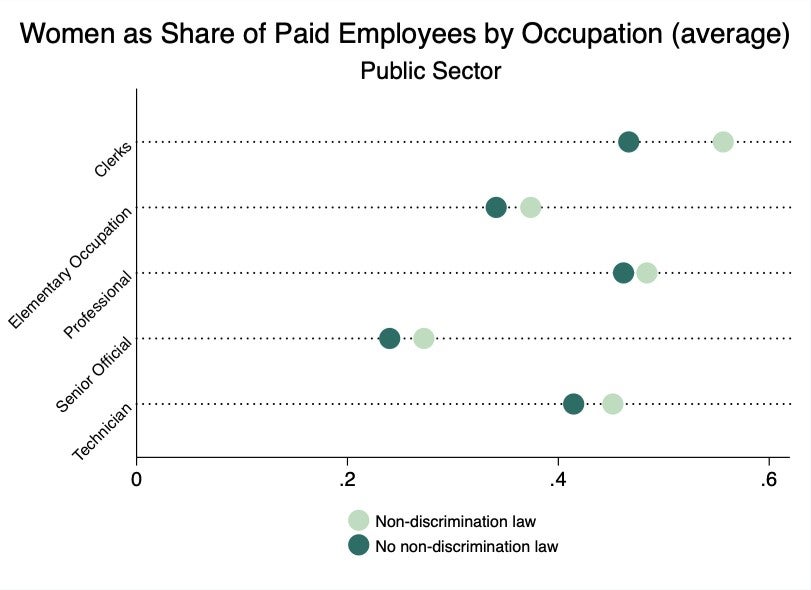

4. Women are better represented across public sector occupations in countries with non-discrimination laws than in those without them.

From clerks to senior officials, women are better represented across the public sector in countries with non-discrimination laws. However, only clerks achieve equal representation. Significant work remains to be done to achieve gender parity across occupations in the public sector.

5. The positive link between non-discrimination laws and occupational representation is weaker — and sometimes reversed — in the private sector.

In fact, in the private sector, countries with non-discrimination legislation have lower shares of women in Senior Official and Professional positions than countries without them. The public sector, then, emerges as a leader in implementation of non-discrimination laws, while the private sector falls short. Further research may focus on the enforcement of non-discrimination legislation between sectors, the associated employment and wage prospects by gender, and the ways in which these factors may pull or push women between the public and private sectors.

6. Countries with non-discrimination and equal pay laws are, on average, richer, more educated, and more economically equal. They have lower rates of self-employment, especially for women, and higher total labor force participation, an effect driven entirely by women.

The particular economic, political, and social environments in which non-discrimination and equal pay laws exist make the causal impact of such legislation difficult to assess. We know that in countries with non-discrimination laws, a greater share of women work in the public sector. We also know that, in these cases, women are better represented across occupations.

But in which particular conditions does equal pay and non-discrimination legislation succeed in boosting female representation and advancement in the public sector? What policies work complimentarily? What type of public-private or private-public labor flow accompanies these shifts — and what implications do they hold for public sector productivity and overall welfare?

As the database on civil servants grows, we can continue strategically analyzing best practices for achieving gender equality in the public sector both legally and substantively — and then structure our frameworks accordingly.

Join the Conversation